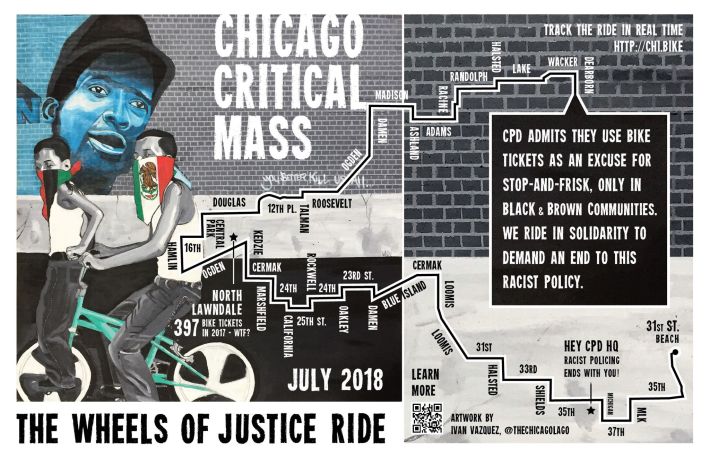

In June a Chicago Police Department representative acknowledged that the massive discrepancies in the number bike tickets written in some African-American and Latino communities versus majority-white areas is due to officers using traffic enforcement as a strategy to conduct searches in high-crime neighborhoods. In the most extreme example, 397 citations were issued in majority-Black North Lawndale in 2017, versus only five in bike-friendly, mostly white Lincoln Park, according to a report by the Chicago Tribune’s Mary Wisniewski. Remarkably, the CPD rep said he doesn’t believe this is a racial equity issue, since the demographics of those ticketed reflect those of the communities, and he indicated that the CPD doesn’t plan to end this policy.

As a protest against the CPD’s zero-tolerance bike enforcement in Black and Brown communities, last Friday participants from Chicago Critical Mass staged the Wheels of Justice Ride. This CCM route that headed west from downtown to North Lawndale, and then southeast to the main police headquarters in Bronzeville. “We ride in solidarity to demand an end to this racist policy,” the route map stated. Roughly a thousand bicyclists took part in the high-energy ride, which was one part demonstration and one part celebration.

As the ride assembled under the Picasso sculpture in downtown Daley Plaza, I asked several bike riders of color for their perspective on the ticketing issue. None of the people I spoke with had recently received bike citations, but some of them reported previous run-ins with police officers, and they all said they supported using Critical Mass as a vehicle for raising awareness of the problem.

Darryl Edmonds, who has ridden in Critical Mass on and off for the last decade, told me that his only confrontation with the police happened more than a decade ago. “I was heading towards the Museum Campus [on Roosevelt Road] and for some reason, this cop wouldn’t let any bicycles come through,” he recalled, adding that this seemed to make no sense because “there was no festival going on.”

Albany Park resident Julio Rivera has ridden in the Mass for three years. He recalled one occasion when he, his brother, and some friends were riding bikes in the largely Latino Northwest Side neighborhood when they were pulled over by the police for questioning, seemingly at random. “We ride a lot in the city, usually on a weekly basis,” he said. “We’ve been pulled over only once. They [said they] were wondering why we were outside at 9:00, which is not even that late.”

Rivera added that when his brother worked downtown making deliveries by bike, it was fairly common for him to get pulled over by the police. “They were saying his bike was too good for him to afford it, which wasn’t true because he basically customized and built it.”

Far North Side resident Kay Dixon, who has rolled with Critical Mass for four years, said he’s never been pulled over while biking, but the issue of unfair ticketing is on his radar. . “I have not had that experience yet, and I do say ‘yet,’” he stressed. “One of the main reasons I made sure I was at this ride was because of the theme… I know [police targeting cyclists of color] is a prominent thing that happens in Chicago.”

Logan Square resident Marcus Kyler has been doing the ride intermittently since 2012. He told me he thinks that the fact that bike lanes are less common on the South Side than the North Side is a factor in the high number of bike citations in some Black and Latino areas. “The South Side is not as bike-friendly a place to ride, so you would be better off riding on the sidewalk,” he argued.

While all of the riders I interviewed appreciated the theme of the Wheels of Justice Ride, there were different opinions about how effective it would be in raising awareness of the ticketing issue. “Nobody’s gonna know what’s going on, just because we’re riding through the city,” Kyler said. “Unless somebody explains it, I don’t think anything is going to be affected by it.”

“I believe [the ride is] just to get us all united, and let the CPD know that our voices are heard,” Rivera said.

“I don’t know if ‘proud’ is the right word, but I was very appreciative that [the route organizers] thought to dedicate an entire ride in solidarity with bicyclists on the South and West sides and people who look like me,” Dixon said.

As it happened, when Critical Mass finally took to the streets, the ride seemed to get its warmest receptions in the Black and Brown communities we passed through on the South and West sides. For example, as we pedaled on the ring road around the Douglas Park green space, picnickers waved hello and shouted the Chicago Critical Mass catchphrase “Happy Friday!” back at us. And as we proceeded west into North Lawndale, the neighborhood that was hardest-hit by ticketing last year, young boys stood on the side of the road to high-five the riders as we passed by.

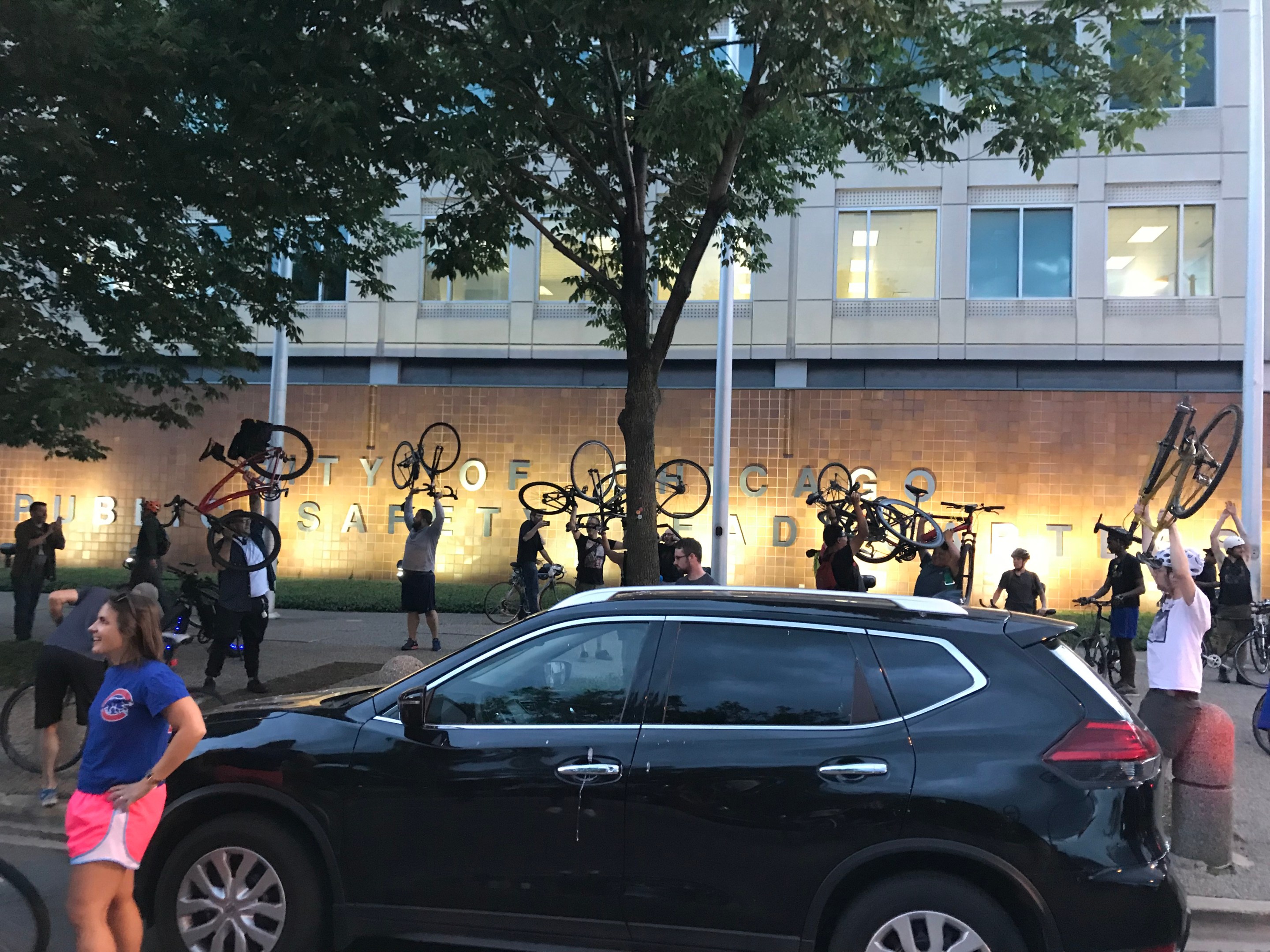

However, things did get a little tense near the end of the ride when Critical Mass arrived at the main CPD headquarters and the crowd of riders occupied the streets in front of the station for a good fifteen or twenty minutes. But police officers didn’t confront the demonstrators, let alone arrest anyone, and the action ended with a peaceful, but defiant, “Chicago Hold-up” – riders holding their bikes aloft over their heads.

It’s not clear whether the ride achieved its goal of raising awareness of the CPD’s bike enforcement practices in the neighborhoods that are most affected, although some riders passed out flyers outlining the problem to residents. But, if nothing else, police department officials are now aware that this issue is on the radar of hundreds of cyclists, and it’s likely this won’t be the last time the CPD encounters resistance to its racially imbalanced bike ticketing policy.