There's an obscure intraregional battle happening in the Cleveland area right now that highlights an important source of racial discrimination in urban planning.

The regional planning agency, NOACA (short for Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency), is governed by a board that is disproportionally white and favors suburban interests. The board has six representatives from the city of Cleveland (population 385,000, 53 percent black). Meanwhile, quasi-rural Geauga County (population 94,000, 97 percent white) gets three.

In an attempt to better reflect the population -- and at the request of the city of Cleveland -- NOACA's governance committee recently voted to amend its bylaws to give Cleveland two additional seats. It wouldn't be enough to fully correct the imbalance, but it would make things fairer.

Now Geauga County leaders are balking. The Geauga Maple Leaf reports that county commissioners have refused to approve the resolution for the second year in a row, postponing its enactment.

NOACA distributes tens of millions of federal transportation dollars across the Cleveland region annually. With proportionately less representation on the board, Geauga County would have less power to steer this spending toward the sprawl-inducing projects it has benefited from at the expense of poorer cities like Cleveland.

This pattern is not unusual. According to a 2006 study by the Brookings Institution [PDF], the governance structures of regional planning agencies routinely favor suburbs and white people, just like NOACA's.

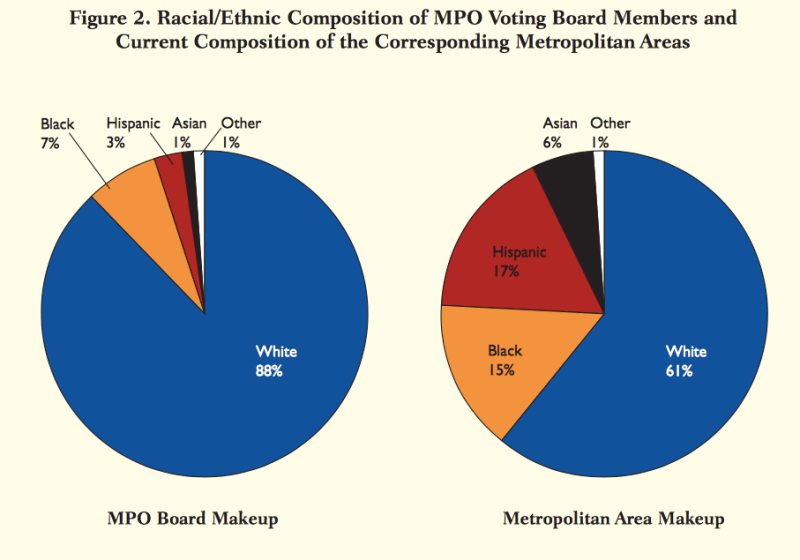

The imbalance is reflected in the racial breakdown of who gets decision-making power at regional planning agencies. Brookings examined the demographics of 50 boards. As you can see in the above chart, blacks, Latinos, and Asians were all underrepresented. A quarter of the boards were 100 percent white.

Cities are also underrepresented. According to Brookings, if cities had representation in proportion to their population, they would have about twice the voting power.

The suburban skew of regional planning agencies favors highway spending and other sprawl-supporting infrastructure and the expense of city infrastructure like transit. Brookings found that for each additional suburban representative at a regional planning agency, the allocation to transit fell 1 to 7 percent.

Milwaukee is one of the most egregious examples. Its regional planning agency, SEWRPC, gives Milwaukee (population 600,000) zero representatives on its 21-member board. Instead, each county is apportioned three votes, even rural Walworth County (population 100,000).

Houston is another bad example. The region's most populous area -- Harris County -- has one representative on the regional planning agency for every 567,254 residents. Residents of the seven suburban counties have almost four times the voting power: one vote for every 149,240 people, according to research by local advocate Jay Crossley.

Women are also underrepresented, Crossley found. Across Texas, 80 percent of board positions at regional planning agencies are held by men. For the Houston region, the entire executive board is white men.

Back in 1971, Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes -- the first black mayor of a major American city -- led a major campaign against the city's underrepresentation at NOACA. He was able to get HUD to temporarily decertify the agency in 1971.

More recent civil rights challenges to the structure and representation of regional planning agencies have met with less success. A number of court decisions have held that the standard of "one person, one vote" doesn't apply to regional governments, because they have limited authority compared to city and state governments.

Even when agencies do the right thing and try to restructure themselves more fairly, the politics can be tricky, as the Cleveland case illustrates.