Occasional Streetsblog Chicago contributor Daniel Kay Hertz recently published an excellent piece in the South Side Weekly that lays out the reasons why it’s so much easier to get around Chicago’s North Side than the South Side. He also proposes commonsense near-term changes we can make to improve South Side transit, and our transportation network in general, specifically building more transit-oriented development, creating rapid-transit service on Metra lines and adding time-saving features to existing bus service. I’d definitely recommend setting aside some time to give Hertz’s long-ish article a careful read, but in the meantime, here are a few of his key points.

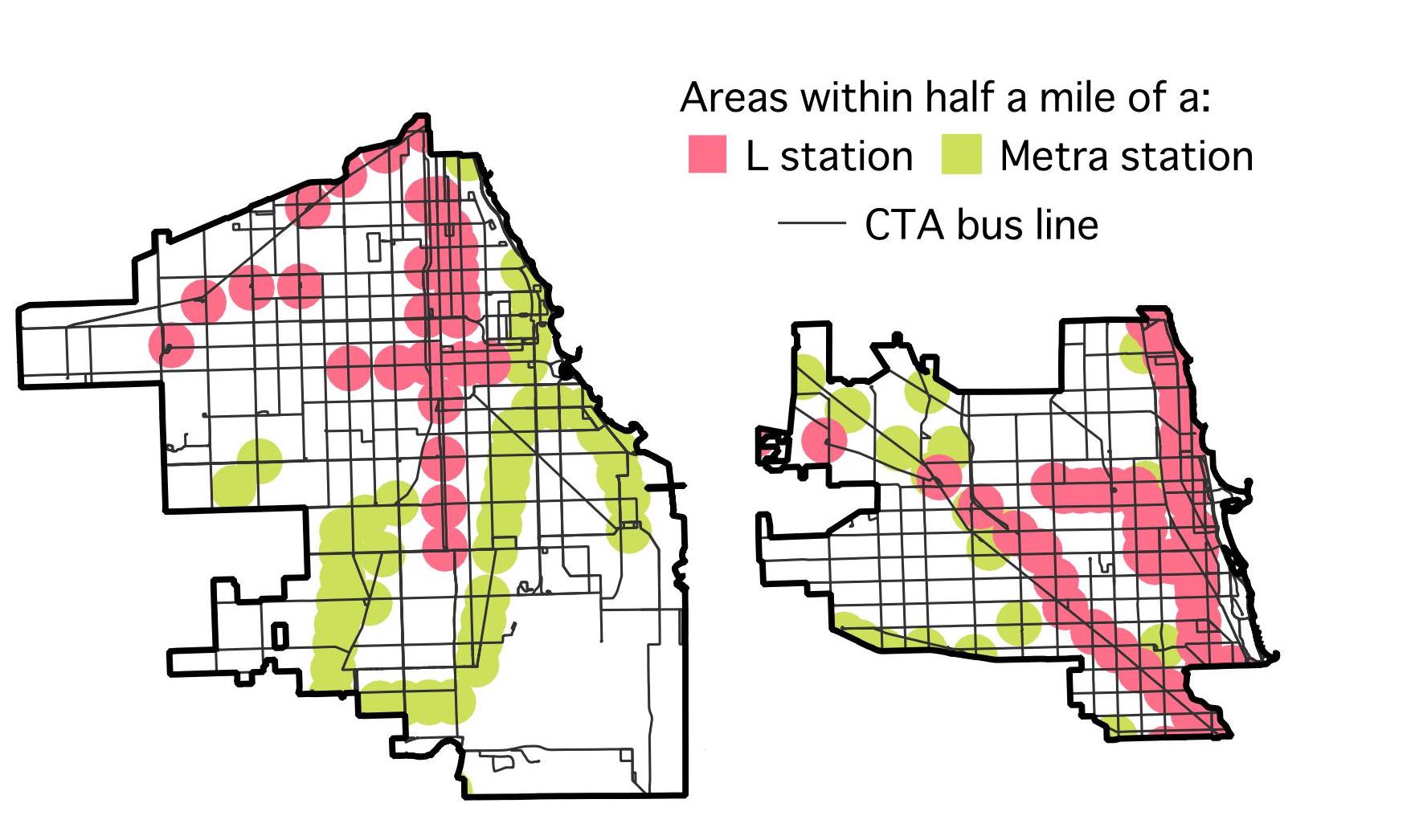

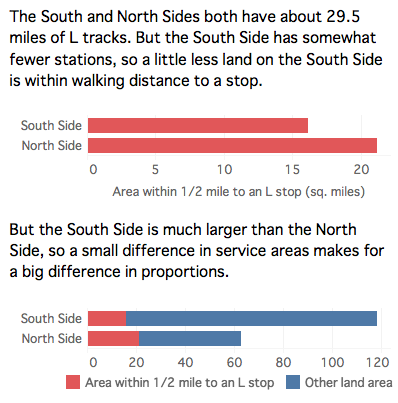

Hertz notes that, when it comes to effective transit service, density is destiny. Defining the North Side as all community areas north of North Avenue, plus West Town, and the South Side as all communities south of the Stevenson Expressway and the South Branch of the Chicago River, the two parts of town both have about 1.1 million residents. They also contain almost exactly the same number of miles of ‘L’ tracks: 29.4 miles on the North Side and 29.7 on the South Side.

However Hertz notes, the South Side’s population is spread over an area almost twice as large as the North Side’s. That lack of density is due to several factors, including more industrial land uses, many neighborhoods with relatively little multi-unit housing, and the destruction of dense housing previously occupied by African Americans during the urban renewal area and the Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan for Transformation.

As a result of less density on the South Side, the same CTA rail mileage serves a smaller percentage of the population than on the North Side. This discrepancy seems to be getting worse, since there’s currently a transit-oriented development building boom going on in North Side neighborhoods like Lincoln Park, Lakeview, Wicker Park, and Logan Square, while South Side ‘L’ stations aren’t attracting anywhere near as much development.

Hertz notes that, even within a ten-minute walking distance from CTA stations, the South Side had barely more than half as many residents as the North Side, on average 15,000 people compared to 29,000. Moreover, for every three jobs located within walking distance of a North Side ‘L’ stop, there’s only one job easily accessible from a South Side station.'

Hertz points out that another factor in why the ‘L’ system is currently more useful for North Siders than South Siders is that the North Side has over fifty percent more people who work in the Central city. Our hub-and-spokes train system doesn’t work as well on the South Side, which has a much larger proportion of seniors and children, who are more likely to be traveling to local destinations like schools, shopping, and medical appointments. That’s one reason why bus service, rather than trains that head downtown, is more important to South Siders.

To start fixing the inequality of Chicago transit access, Hertz proposes building more housing, both affordable and market-rate, job centers, and other amenities, close to train stations on the South Side. “The city’s community development efforts—from attracting new businesses and employers to locating new libraries or other city services—should also be located with an eye to transit accessibility,” he writes.

Although the city is hoping to extend the Red Line to 130th in the foreseeable future, building new ‘L’ lines is a very slow, expensive process. However, Hertz notes, many South Side community lines are already served by Metra routes that have the same half-mile spacing as most parts of the CTA train system. All that needs to be done to make them much more useful for local residents is implement more frequent service and allow Ventra card payment.

And, since a much higher proportion of South Side transit trips are made by bus than North Side journeys, speeding up bus service would go a long way towards improving mobility for South Siders, Hertz writes:

In cities where transit does well, civic leaders work from the belief that the most equitable, sustainable, and space-efficient forms of transportation ought to be prioritized. Bringing that attitude to Chicago would mean speeding up buses by allowing people to pay at both the front and back doors (or, even better, before the bus arrives at all), creating bus lanes, and making sure buses come on a regular, frequent schedule. An added bonus would be even more clean, bright bus shelters that provide seating, protect riders from the elements, and give information about arrival times.

Hertz concludes by acknowledging that making transit more accessible and efficient on the South Side won’t solve all of Chicago’s deep-seated social justice problems. “[But it will help create] a more humane city, in ways big and small. Envisioning what accessibility might look like on the South Side is, hopefully, one modest step towards that kind of city.”