In September 2016 Chicago announced it would be releasing a multi-departmental Vision Zero plan later that fall, with the goal of completely eliminating traffic deaths within a decade. It’s almost spring now and they still haven’t put out the document. But a full presentation on the plan at last week’s Mayor’s Bicycle Advisory Council meeting indicates that the city has made some progress on the plan and we should be seeing the fruits of their labor soon.

“We’re committed to eliminating serious and fatal traffic crashes by 2026,” said Chicago Department of Transportation deputy commissioner Luann Hamilton during the presentation. “The assumption is that severe crashes are not ‘accidents,’ that they’re preventable.”

Hamilton noted that 544 people were killed and another 9,480 were injured in crashes on the streets of Chicago between 2010 and 2014, according to Illinois Department of Transportation numbers (2014 is the last year for which this data is available). That’s an average of more than 108 deaths a year.

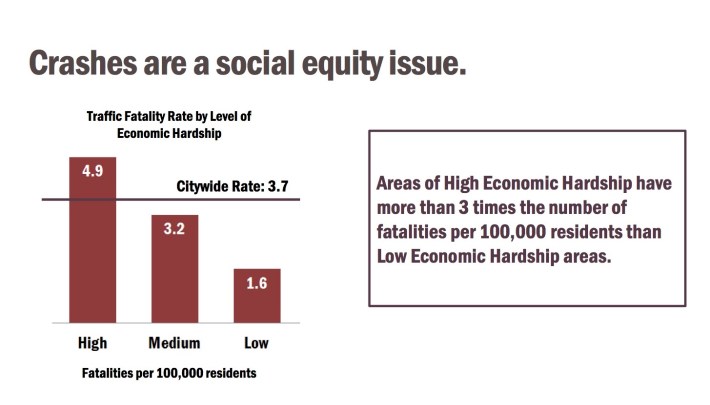

She noted that crashes are a social equity issue. According to Chicago Department of Public Health data, parts of town classified as having high economic hardship have more than three times the number of crash fatalities per 100,000 residents as areas of low economic hardship.

Hamilton said a dozen city departments and sister agencies have been working for the past year or so on a three-year Vision Zero action plan that will be in effect through 2019. The action plan establishes the interim goals of reducing traffic deaths by 20 percent and serious injuries by 35 percent by 2020. Of course, after that there will be only six years left to eliminate the remaining 80 percent of current crash fatalities by 2026, which seems like a tall order.

To accomplish these goals, the city plans to concentrate infrastructure, education, and enforcement efforts on neighborhoods disproportionately affected by traffic violence. “Rather than spreading the peanut butter too thin, we’re taking the approach of determining where the problems are most severe and then focusing our resources there,” Hamilton said. However, she added that there will also be citywide initiatives.

The community areas singled out for special attention are Belmont Cragin, Austin, West Garfield Park, East Garfield Park, North Lawndale, Humboldt Park, West Town, Near West Side, Near North, Loop, West Englewood, Washington Park, and Grand Boulevard. According to CDOT, these areas contain 20 percent of the city’s geographic area and 25 percent of its population, but 36 percent of serious crashes have occurred within them. These areas include basically everything west of the Loop, plus a few Mid-South communities.

Hamilton acknowledged that there have been concerns about the lower-income communities of color on this list being unfairly targeted for police enforcement. “Given that we know that these areas of high economic hardship are really vulnerable, we don’t want to be issuing a lot of citations in these neighborhoods and causing additional hardship in areas where people are suffering,” she said.

Instead, meetings will be held with community stakeholders to help determine what strategies are most appropriate, Hamilton said. The idea is for residents to take ownership of the traffic safety efforts and collaborate with the city and police on reducing the number of serious crashes. “So we might be more likely to have police pull people over an send them to some kind of [traffic safety] training program rather than ticketing them.”

Rosanne Ferruggia, the city’s Vision Zero coordinator, has been leading the planning process for the initiative on the city side. She told the meeting attendees that the city’s Safe Routes Ambassadors pedestrian and bike safety outreach team will be key for spreading the word about safe travel in the targeted communities.

The three-year action plan calls for measurably changing behaviors and notions about traffic crashes to build a culture of safety, Ferruggia said. She noted that 72 percent of fatal crashes involve speeding, failure to yield the right of way, cell phone use, intoxicated driving, or disobeying traffic signals and signs. The city hopes to have 100,000 residents sign a Vision Zero Pledge stating that they understand these issues and commit to behaving more safely on our roads.

Other Chicago Vision Zero goals include increasing the percentage of adults who commute to work by walking, biking, or taking transit by ten percent by 2020, and reaching 50 percent of commuters using active transportation by 2030. As part of that, the city plans to improve pedestrian infrastructure at 300 intersections, including infrastructure like pedestrian islands, curb bump-outs, and walk signal countdown times, as well as completing 50 miles of bike lanes within Mayor Emanuel’s second term.

The city also hopes to eliminate fatal crashes involving city vehicles, CTA buses, and taxi and ride-share drivers by 2020, and ensure that training for city fleet drivers, CTA bus drivers, and city-regulated drivers includes Vision Zero curriculum. Ferruggia noted that half of the six fatal bike crashes in Chicago in 2016 involved turning truck drivers, and said the city will work with private industry to create recommendations for safety equipment, such as convex mirrors and truck side guards, to help prevent these kinds of tragedies.

After the three-year action plan is released, the city will meet with community residents and organizations to come up with specific plans for the eight high-crash community areas. To stay abreast of these developments, you can sign up e-newsletters at the city’s Vision Zero website.

After the presentation, Active Transportation Alliance director Ron Burke brought up the importance of working with the Illinois Department of Transportation on the initiative. He noted that only 7.6 percent of roads in the region are under IDOT jurisdiction, but 35 percent of serious crashes take place on these IDOT roads, and the proportions are similar on state-controlled streets in Chicago, such as Ashland and Western. Although the state has historically focused on moving vehicles quickly, rather than designing streets that are safe for all road users, “we’re going to have trouble meeting the Vision Zero goals without IDOT’s help,” Burke noted.