[The Chicago Reader recently launched a new weekly transportation column written by Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield. This partnership allows Streetsblog to extend the reach of our livable streets advocacy. We syndicate a portion of the column on the day it comes out online; you can read the remainder on the Reader’s website or in print. The paper hits the streets on Thursdays.]

As a sustainable ransportation advocate, I'm jazzed whenever land that's been unnecessarily earmarked for moving or storing automobiles is put to more productive use.

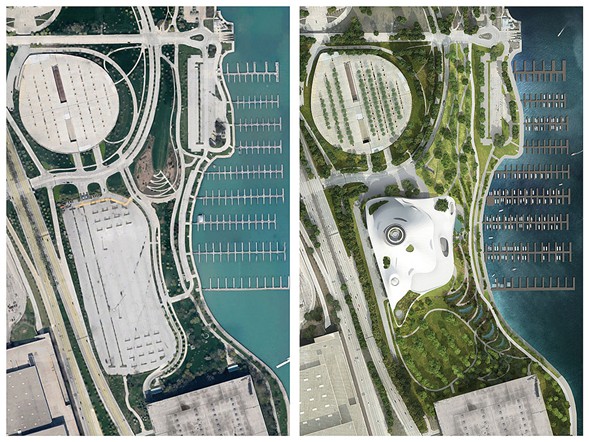

So when Mayor Emanuel first proposed bringing the Lucas Museum of Narrative Arts to Chicago two years ago, one of the potential benefits that most excited me was the prospect of replacing a 1,500-car parking lot with a world-class cultural amenity, plus four acres of new green space.

The ugly expanse of asphalt where the museum would have gone is Soldier Field's south lot, located on prime lakefront real estate between the football stadium and McCormick Place's monolithic Lakeside Center.

Granted, this blacktop blemish also serves as a spot for tailgating, an age-old Chicago Bears tradition. In addition, it accommodates other special events that generate revenue for the city. But the Lucas plan would have largely moved the surface parking off the lakefront, while providing new tailgating opportunities in other locations.

So I was bummed when the advocacy organization Friends of the Parks launched a legal battle against the south lot proposal. While the group said it supports bringing the Lucas facility to our city, it argued that building it on the parking lot site would violate the city's Lakefront Protection Ordinance, which states that "in no instance will further private development be permitted east of Lake Shore Drive."

"Although the proposed site is now used as a parking lot, its future reversion to parkland is possible," FOTP's then-president Cassandra Francis said in May 2014. "Once a building is in place, it is forever precluded from being public open space."

Emanuel razzed the parks group for its seemingly pro-tarmac stance, mocking it as "Friends of the Parking Lot." Gino Generelli, a local tech company owner, launched an online petition asking FOTP to drop its lawsuit. "At a time when Chicago needs an organization like yours to protect actual parks, please do not waste the time and resources generously donated to you to protect a parking lot from the fate of becoming a world-class cultural institution," he wrote. More than 1,500 people have signed so far.

I was similarly annoyed. FOTP's stated mission is "to preserve, protect, improve and promote the use of parks and open spaces throughout the Chicago area for the enjoyment of all residents and visitors." It seemed to me that fighting the south lot plan conflicted with that goal.

At this point, it looks like FOTP has effectively deep-sixed the south lot plan. Last February a federal judge denied a motion by the city to dismiss the lawsuit. Litigation could take years. Lucas, 71, has made it clear he's not willing to wait much longer to break ground—he wants the museum to be completed while he's still able to enjoy it.

As a last-ditch attempt to keep the museum here, in mid-April Emanuel announced an alternative plan to demolish Lakeside Center to make room for the museum. (A new "bridge building" over King Drive would replace lost convention space.) To sweeten the deal, this plan would create a full 12 acres of new parkland.

That seemed to appeal to Friends of the Parks, which released a statement last Thursday that the group is open to the proposal. "We are pleased that the mayor and the city recently opened the door to . . . more direct conversation about the Lucas Museum," said executive director Juanita Irizarry.