Earlier this month public transit consultant Jarrett Walker ran a post on his blog Human Transit that’s highly relevant to Chicago as we weigh the pros and cons of Mayor Emanuel’s proposal for an express train to O’Hare. In Walker’s article “Keys to Great Airport Transit,” he argues that certain elements are crucial for providing useful and financially sustainable public transportation access. Let’s take a look at how the O’Hare plan, which is currently being brainstormed by the engineering firm Parsons Brinkerhoff, might measure up.

Walker starts outs with a cautionary tale for Chicago as we consider the O’Hare express, which officials say would cost between $25 and $35 dollars to ride. Toronto's Union Pearson airport express has seen disappointing ridership numbers that have continued to drop. Apparently, not many Torontonians are in a rush to take the train to YYZ.

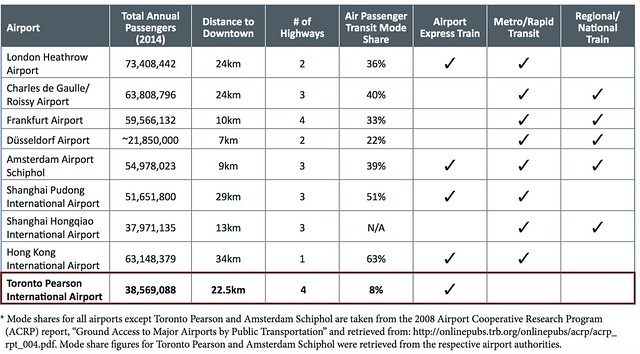

Walker argues this is because the fare is too high, at about $20 U.S., and the service doesn’t connect to enough places. He shares the following chart from the recent Pearson Connects study, a transportation plan for Pearson Airport by Urban Strategies, Inc. It suggests that airports that are connected to a city’s whole rapid transit network, not just a route to downtown, have a higher air passenger transit mode share.

By that measure, O’Hare already has pretty good rail access. The Blue Line offers a direct connection to many different parts of town, and it’s easy to transfer to most of the other ‘L’ lines once you reach the Loop. It’s also an affordable, efficient way to get to work for hundreds of airport workers.

“To create a great airport train (or bus) for air travelers, you have to make it useful to airport employees too,” Walker writes. “That generally means a service that’s an integral part of the regional transit network, not a specialized airport train.” The Blue Line fits that bill.

Walker notes that it’s highly desirable to have rail service that doesn’t just terminate at the airport, like the Blue Line does. He cites Sydney and Seattle as best practices, and Washington, D.C.’s Metro service to Reagan National Airport also springs to mind: You can keep traveling beyond the airport to outer suburbs.

Right now, you can also access O’Hare via Metra’s North Central Service by getting off at the O’Hare Transfer station on the northeast side of the airport, catching a shuttle bus, and then the airport’s people mover to the terminals. While this method is a bit convoluted, it serves as a transit route to the airport for people who live north of O’Hare along the North Central line, as far as Antioch, Illinois, near the Wisconsin border.

Using the North Central right-of-way for the O’Hare express is a likely scenario, although a direct rail connection to the airport would be necessary to make the service appealing to business travelers. If a tunnel is built to provide that connection, it would add value to the project if Metra trains are also able to access the terminal, providing folks who live north of O’Hare with a direct route to the airport.

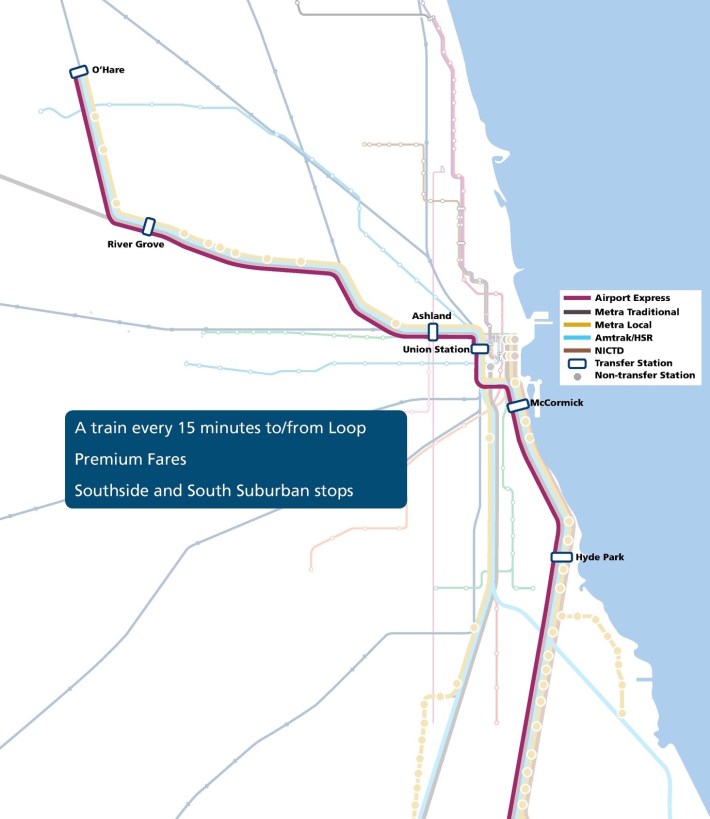

Moreover, if the O’Hare express is done as part of the Midwest High Speed Rail Association’s CrossRail proposal to connect the North Central Service with the Metra Electric District Line on the Southeast Side, the project could have even more utility.

Walker points out that, even if an express train has a shorter "in-vehicle time" than one that stops more often, there is often little overall time savings if the frequency of service is lower on the express. As local urban planner Daniel K. Hertz noted in a recent Chicago Magazine piece, while the Blue Line runs every four minutes during rush hour, the O’Hare express will likely have 15-minute headways, which would nullify much of the timesaving advantage.

And, since the express would likely terminate in the West Loop, farther from Michigan Avenue hotels than the Blue Line stops on Dearborn Street, the need to take an additional taxi or bus trip would further reduce the appeal of the express train.

Walker recommends offering service for airport travelers and employees on the same train. “This is a case of the general principle that transit thrives on the diversity of trips for which it’s useful, not on specialization,” he writes. “If elites want a nicer train, give them first class cars at higher fares, but not a separate train just for them... As always, the more people of all kinds you can get on a train or bus, the more frequently you can afford to run it, which means less waiting, and the lower the fare you need to charge.”

Chicago aviation chief Ginger Evans has argued that lawyers and bankers traveling to and from O’Hare want a quiet place where they can talk on the phone or pull out a laptop. If that’s the case, perhaps there would be a market for first-class cars on the Blue Line. Since a nonstop train wouldn’t get travelers to their hotels much faster anyway, a nicer car attached to the end of the Blue Line wouldn’t necessarily be a downgrade from pricey express service.

Hopefully the city will consider some of these ideas as alternatives to simply building an expensive train that only travels between the airport and the Loop, increasing the project's chances for success.