At a panel discussion hosted Wednesday night by the Lakeview Chamber of Commerce and Lake View Citizens’ Council, two local urban planners and a small business owner explained why they're supporting Mayor Rahm Emanuel's proposed TOD reform ordinance. The new legislation, which City Council could vote on as early as September 24, would dramatically expand the zones around rapid transit stations in which developers are freed from the city's usual parking minimums and can build at a higher density. This would make it easier for Chicago to grow its population while maximizing the number of residents who have access to low cost transportation.

At the forum, titled "Does Lakeview Need More TOD?," Center for Neighborhood Technology planner Kyle Smith told the audience that there are two different ways to define TOD. First, there's the wonk's definition of TOD as building higher-density, parking-lite development close to train stations. However, he said a better way to think about TOD is "communities built for people, not for cars, so that you can live your life without having to own a car."

Peter Skosey, executive vice president at the Metropolitan Planning Council, noted that Chicago lost 200,000 people from 2000 to 2010. "TOD is a great way to provide options in urban places," he said, adding that it can help Chicago regain its lost population.

Panel member Lisa Santos has owned Southport Grocery at 3552 N. Southport Ave. for 12 years. She said her store and other local businesses need a bigger and more diverse clientele in order to maintain and grow sales. She said that more TOD will help "develop a neighborhood for the next generation."

Earlier this year, the chamber and CNT produced a report about housing and population changes near the Brown Line's Southport and Paulina stations in West Lakeview. It found that the number of nearby housing units within a half mile of each 'L' stop decreased by 2 percent and 4 percent, respectively, from 2000 to 2011. The number of small apartments – studios and one-bedrooms – dropped by 33 percent. "Younger folks choose these apartments," Smith said, adding that if compact units aren't available, it's harder for them to afford living in Lakeview.

Skosey mentioned that Chicago's population is growing at one-fifth the rate of Minneapolis, "so it's not the weather" that's holding Chicago back. Building more housing near train stations is a way Chicago can leverage our relatively robust transit system to encourage growth.

However, at community meetings about proposed TOD projects in Chicago, many neighbors seem to view additional density as a problem. They appear to be more worried about preserving their own access to free on-street parking than reversing our city's population loss.

"What happens when those renters earn more money and want to buy a car?" one resident asked at the forum. Smith responded that we're seeing a generational shift toward less car ownership, which he believes will be permanent. Another argument he could have made is that, if tenants eventually opt for car ownership, they may choose to move to a building with parking or to rent an off-street parking space.

Smith pointed out that the rate of car ownership among new residents who move in to parking-lite TOD buildings will probably be lower than that of existing residents. That means that, even though 60 percent of current Lakeview households own cars, it's unlikely to create a parking crunch if a TOD developer provides less than 60 spaces for a 100-unit building.

He gave the example of the 1611 West Division building, located next to a Blue Line stop in Wicker Park. It features 99 apartments and zero car parking spaces for tenants, but it was almost fully rented within a few months of completion. To reassure neighbors that they wouldn't have added competition for free parking on side streets, the renters are ineligible for residential parking permits.

Alan Mellis, a Lincoln Park resident who attends many public meetings, said he's concerned that neighbors would have less input on developments under the revised TOD ordinance. The new law would drop the current requirement for the alderman to sign off on dense, parking-lite developments – when a zoning change is needed – and instead leaving approval up to the city's zoning administrator. "When you involve the community the development always gets better," Mellis said.

However, the new approval process, called an "administrative adjustment", wouldn't be any more or less problematic than the current piecemeal development process. Currently, the alderman is under pressure to bow to the opinions of the armchair urban planners who show up for community meetings. Under the new legislation, the aldermen would still be able to provide input to the zoning administrator and influence his or her decision.

One person in the audience noted that community members have supported two TOD buildings at the Paulina station, and one at the Southport stop. "Why build more TODs until we understand the impact of the current three?" he asked.

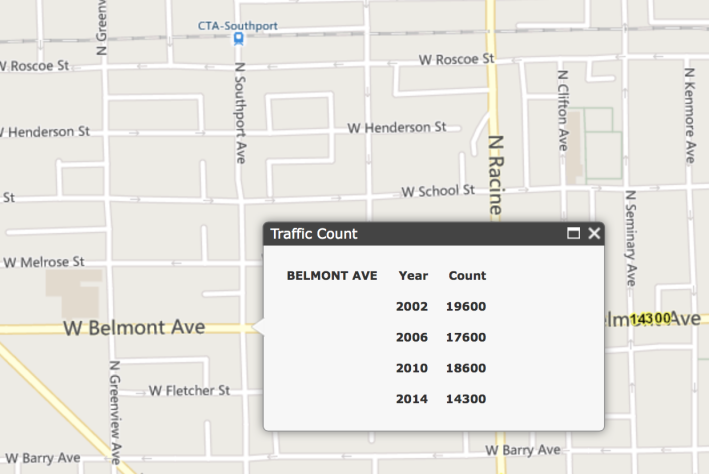

Skosey replied that neighborhoods with TOD buildings have absorbed them well. "Many historic rental buildings have had zero parking for 100 years, and we've dealt with that," he said. He added that the number of car trips per day on Belmont Avenue in Lakeview has fallen by 27 percent, eliciting a gasp from the crowd. I looked up traffic counts on Belmont near Southport and found that they fell even further at that location from 2010 to 2014, by 31 percent.