This is the first post in a three-part series on the Indiana Toll Road and the use of private finance to build and maintain highways.

In September, the operator of the Indiana Toll Road filed for bankruptcy, eight years after inking a $3.8 billion, 75-year concession for the road with the administration of Governor Mitch Daniels.

The implications of the bankruptcy for the financial industry were large enough that ratings agency Standard & Poor's stepped in immediately to calm nerves. In a press release, the company attempted to distinguish the Indiana venture from similar projects, known as public-private partnerships, or P3s: "We do not believe this bankruptcy will slow the growth of current-generation transportation P3 projects, which have different risk characteristics."

But the similarities between the Indiana Toll Road and other P3s involving private finance can't be ignored. And as we'll see, even the differences aren't good news for the American public. Once hailed as the model for a new age of U.S. infrastructure, today the Indiana deal looks more like a canary in a coal mine.

At a time when government and Wall Street are raring to team up on privately financed infrastructure, a look at the Indiana Toll Road reveals several of the red flags to beware in all such deals: an opaque agreement based on proprietary information the public cannot access; a profit-making strategy by the private financier that relies on securitization and fees, divorced from the actual infrastructure product or service; and faulty assumptions underpinning the initial investment, which can incur huge public expense down the line. Though made in the name of innovation and efficiency, private finance deals are often more expensive than conventional bonding, threatening to suck money from taxpayers while propping up infrastructure projects that should never get built.

For the parties who put these deals together, however, the marriage of private finance and public roads is incredibly convenient. Investors are increasingly impatient with record-low returns on conventional bonds, and are turning to infrastructure as an asset class that promises stable, inflation-protected returns over the long run.

Meanwhile, governments are eager to fix decaying infrastructure -- but without raising taxes or increasing their capacity to borrow. On the occasion of yet another meeting intended to drum up investor interest, Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx recently wrote on the U.S. Department of Transportation's blog: "With public investments in our nation’s important transportation assets steadily declining, we need to find better ways to partner with private investors to help rebuild America."

Those investors are lining up to get in the infrastructure game. According to the Congressional Budget Office, about 40 percent of new urban highways in America were built using the private finance model between 1996 and 2006. Since 2008, that figure has jumped to almost 70 percent.

In an attempt to get even more deals done, the current federal transportation bill ramped up funding for the TIFIA program -- which offers subsidized federal loans and other credit assistance, often to projects that also receive private backing -- by a factor of eight.

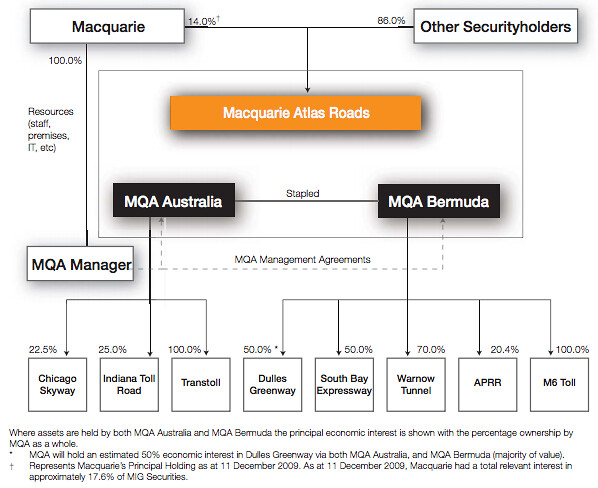

Major private investors have stepped up their lobbying efforts to close more of these lucrative deals. Meridiam North America recently hired Ray LaHood, Foxx's predecessor as Transportation Secretary, and Macquarie Group -- which orchestrated the Indiana fiasco -- hired away a White House deputy assistant to "continue strengthening our relationships with key elected officials... while also exploring new investment opportunities."

In the midst of all this excitement about an "emerging market" in privately-financed American road-building comes the big failure of the Indiana Toll Road. In the news cycle following the bankruptcy, pundits praised former Indiana governor Mitch Daniels for deftly negotiating the deal. Many experts seem to think that the state of Indiana will almost entirely be shielded from the fallout of this bankruptcy, since it already received its payout and retained the right to set the road's tolls and enforce its maintenance standards. (That is often not the case in these kinds of deals. Note how Standard and Poor's says that newer infrastructure deals have "different risk characteristics" -- that is, more of the risk falls on the public, something we'll discuss in the third installment in this series.)

At the time of its sale in 2006, the Indiana Toll Road was the largest infrastructure privatization deal ever in U.S. history. Investors paid $3.8 billion for the right to operate and collect tolls on the 156-mile road for 75 years. The winning bid raised eyebrows. Sure, the road is heavily traveled by cross-country trucks, but the price was twice what state officials had expected the road to fetch, and $1 billion more than any other group had bid.

But if Indiana did manage to put one over on the financier-owners, Australian firm Macquarie and Spanish firm Ferrovial, as some suggest, those owners don't seem to be too worried. For Macquarie, an investment bank and financial services firm with almost $400 billion under management, the loss hardly even registered as a blip in its share price:

Under the terms of the bankruptcy deal approved last month, ITR Concession Co. LLC -- the company Macquarie and Ferrovial formed -- will either be sold at auction, with proceeds distributed among its creditors, or those creditors will themselves buy a 95.75 percent stake in the restructured company, thanks to a fresh $2.75 billion round of borrowing. ITR began its life as a P3 with $3 billion in bank debt, and ITR's second incarnation could get up and running with $2.75 billion in debt -- not exactly a fresh start.

Bloomberg, The Hill, Reuters and the other outlets covering this story all pinned the downfall of ITR on both a risky financing scheme and on faulty traffic projections. Most sources shrugged off the faulty traffic projections as an artifact of the recession, not as part of a longer-term, more permanent shift in driving behavior that has been widely documented.

Whatever the cause, the Indiana Toll Road's traffic projections were indeed very, very wrong. Although the actual projections contained in the signed contract are proprietary and shielded from public view, the state of Indiana released an analysis they conducted prior to the sale [PDF] showing expected increases of 0.55 percent annually, adding up to 22 percent over seven years. What actually occurred after ITR took over the lease in 2006 was closer to the inverse: traffic declined more than 11 percent.

But even if traffic levels had met the projections, that would not have been enough to save ITR. As Toll Roads News pointed out, predicted traffic growth plus profit-maximizing toll rates still wouldn't have been enough to balance the books for the company:

They'd still only have toll revenues of $245m. And with interest payments to be made to borrowers of $268m they'd still be losing money.

So in addition to faulty traffic projections, ITR relied on a risky financing scheme that inflated its costs.

Media outlets also noted that the ITR bankruptcy was just the latest and largest in a crop of privately owned tollway failures that now litter the land. In recent years, other privately financed toll roads that have filed for bankruptcy protection have included San Diego's South Bay Expressway (also owned by Macquarie and the first project to receive federal TIFIA funds), South Carolina's Southern Connector, and the Alabama and Detroit roads owned by American Roads. Many more are limping along and may well end up bankrupt, like SH-130 outside Austin or the Northwest Parkway between Denver and Boulder.

Bankruptcy or default won't necessarily eliminate the risk of a public bailout. The 12-year-old Pocahontas Parkway outside Richmond has now failed twice, largely because projected sprawl in its vicinity just never materialized. (Instead, Richmond's core is booming, as in other metro areas.) Since TIFIA loans account for one-fourth of Pocahontas' debt, taxpayers will eventually take a hit if the road continues to miss its payments.

Who is Macquarie, and why did it pay so much to run this Indiana highway? What can we learn about private finance in the infrastructure industry by taking a closer look at the Indiana Toll Road? We'll investigate that in our next post, coming up tomorrow.

And then, why were traffic projections so far off base in this case? There's a lot of evidence that engineering firms like Wilbur Smith (now CDM Smith), which produced the faulty forecasts for the ITR, have incentives to inflate traffic projections. We'll investigate that in part three.