[This article also appeared as a cover story in Newcity magazine, which hits the streets on Wednesday evenings.]

I confess that I’m obsessed with pedaling the perimeters of things. For years, I led the Chicago Perimeter Ride, a hundred-mile bicycle tour of the rim of the city, stopping to admire goofy commercial architecture landmarks, from the Eyecare Indian in Westlawn, to the giant fiberglass wieners of Superdawg in Norwood Park. I’ve cycled the circumference of Lake Michigan and the state of Illinois, and I’ve got a Land of Lincoln tattoo on my left shoulder as proof of the latter. I’ve biked three sides of the continental U.S., and some day I hope to complete the circuit by cycling from Key West, Florida, to Bar Harbor, Maine.

Since my journalistic wheelhouse is local transportation issues, it recently occurred to me that I should pedal the perimeter of Chicagoland, as a way to wrap my head around our vast region, and meditate on the urban planning challenges we face. But how best to define the Chicago metro area? There are a number of different definitions of the region, with one of the broadest being the Chicago Metropolitan Statistical Area, originally designated by the U.S. Census Bureau in 1950. Along with Cook and the collar counties, it includes swaths of southeast Wisconsin and northwest Indiana, for a total population of 9,522,434, making this the third-largest MSA by population in the nation.

Somewhat arbitrarily, I opted to define the perimeter of the region as being a route connecting the endpoints of the Metra commuter rail system’s eleven lines. This would allow me to skip the nastier industrial sections of the Hoosier State, since Metra doesn’t serve Indiana, while justifying an excursion across the Cheddar Curtain to quirky Kenosha, Wisconsin, one of my favorite nearby cities.

Bicycling between train stops would also make it easy for friends to parachute in and keep me company on sections of the four-day trek, and then catch a lift home at the end of the day from a different Metra line. Decision made, I planned out my route, dubbed The Metra-Politan Perimeter Ride, using Google Maps’ bike directions. You can view a Google Map of my itinerary here.

The last twelve months have been rough on Metra. In June of 2013, then-CEO Alex Clifford resigned and was given a jaw-dropping $871,000 severance package, which included a non-disclosure agreement. When local politicians questioned the massive payoff, a memo surfaced, indicating that Clifford was forced out of his job by Metra board members after he refused to bow to demands for patronage hiring and promotions. Some of the pressure apparently came from uber-powerful Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan.

Five board members resigned in the wake of the scandal and, last summer, Governor Pat Quinn responded by creating the Northeast Illinois Public Transit Task Force, to brainstorm ways to fight corruption and ensure the regional transit system is properly funded. In March, the blue-ribbon panel recommended abolishing the four boards of Metra, the CTA, Pace and the Regional Transit Authority, in favor of a new superagency to oversee the three transit agencies, similar to how things work in the New York City region.

Getting rid of Chicagoland’s byzantine transit governance system, with a total of forty-seven board members, makes perfect sense to me, but it’s going to be an uphill battle politically. Meanwhile, Metra’s on-time record has been suffering, and scores of train runs were delayed or canceled during last January’s Polar Vortex, leaving crowds of commuters stranded on outdoor platforms in brutal temperatures.

Personally, I’m very fond of Metra. Perhaps because I don’t use it for a daily commute, but only for trips to concerts at Ravinia, plus train-and-bike camping excursions, I associate the system with good times. Unlike the El, Metra cars are generally clean, they have restrooms, you almost always get a seat, and you can legally drink booze. That’s my idea of civilized public transportation.

Ironically, my circuit of Metra endpoints involves zero train riding. After loading up my Clydesdale of a touring bike with saddlebags full of clothes, plus a tent, ground pad and sleeping bag, I start my voyage on Saturday, June 14, around 8am, at the Chicago Cultural Center, upstairs from Millennium Station.

Making my way up the Mag Mile, I take the Oak Street underpass to the Lakefront Trail. The path ends at Kathy Osterman Beach at Ardmore, where the city recently re-marked bike-and-chevron symbols across busy Sheridan Road. Workers also re-striped bike lanes on Winthrop and Kenmore, the main north-south bike routes in the area, and added green paint at conflict areas. When I get to the 6300 block of North Kenmore, I see that it’s blocked off for the construction of a new pedestrian mall on the Loyola University campus.

On my way west, I come across a new Starbucks at Devon and Broadway, made out of recycled shipping containers. That’s pretty cool but, since the coffee shop features a drive-through but zero indoor seating, customers who don’t arrive by car will be literally left out in the cold this winter. I take Clark north into Evanston, past a protected bike lane on Church Street, the only one of its kind in the ‘burbs.

After rolling west from Northwestern University, I pick up the paved Green Bay Trail in Wilmette. Now I’m in the tony North Shore, the setting of classic John Hughes teen flicks like “The Breakfast Club” and “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.” The path soon descends into a small ravine where it runs alongside Metra’s UP / North tracks.

I pedal by the Ravinia gates, and past historic Fort Sheridan. In 1894, federal troops stationed at the garrison stormed the city of Chicago to suppress the Pullman strike. After pedaling on the Robert McClory Bike Path for a few miles, I arrive in Lake Bluff, where I take a pit stop a little before noon at the eponymous brewery, located across the street from the train station. Kicking back outside the pub in the sunshine with a Skull and Bones double pale ale, I think to myself, the suburbs aren’t so bad.

The scenery gets grittier as I continue north into North Chicago, home of Great Lakes Naval Base, and Waukegan, where Jack Benny and Ray Bradbury grew up. Here the bike trail is a crushed limestone path with frequent street crossings, which are annoying. However, the path is lined with community gardens, an encouraging sign in this now-hardscrabble suburb.

After I cross into the Badger State, the path, now called the Kenosha County Bike Trail, is a paved route through the woods, a much more pleasant cruise. As I enter the city of Kenosha, in a park I come across a historical marker for Reuben Deming, a local Methodist preacher and abolitionist, whose home is believed to have been a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Next to the streetcar line that runs between the Metra station and the Kenosha Public Museum, I stumble upon the Rustic Road Brewery, named after Wisconsin’s network of officially designated scenic routes. I don’t mean to spend the entire day drinking beer, but there are a number of bikes parked outside, and a middle-aged couple, drinking at an outdoor table with the woman’s father, urges me to stop in.

I get a Downtown Double IPA and sample some Hazelnut Harvest amber ale, which tastes pleasantly like cream soda. The father has a foreign accent, and it turns out he’s from Vienna. However, unlike his wife, who grew up in the country, he insists that he’s Viennese, not Austrian. The distinction seems to be similar to the way Chicagoans often don’t really think of themselves as Illinoisans.

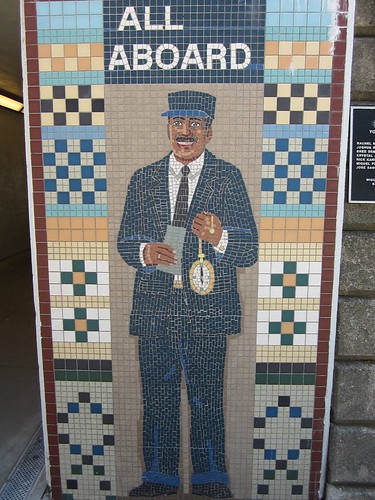

Refreshed, I roll a couple blocks west to tag the local Metra station, which features a charming mosaic of a smiling conductor with a pocket watch. After stocking up on Wisconsin staples like cheese curds and landjaeger sausage at Tenuta’s Deli, it’s time to continue southwest back into Illinois.

Just over the border in Antioch, I visit the last station on Metra’s North Central Service line. Members of the Disciples of Christ founded this town of some 14,000 people. Less-devout residents sarcastically suggested naming the settlement after Antioch, Turkey, an early center of Christianity, and the name stuck.

This section of northern Illinois is dotted with glacial lakes, including the Chain O’Lakes waterway system. The area is popular with boaters and fisherman, and has a bit of a NASCAR vibe. As I continue toward Chain O’Lakes State Park, it’s funny to watch mustachioed men race speedboats across lakes only a mile or so wide, only to have to turn around and zoom the opposite direction.

I pull into the state park at twilight, exhausted after a nearly ninety-mile day. When I arrive at the campground, I see I’m one of the few people who didn’t bring an RV. A well-meaning lady comes up and offers to loan me a tent as if, with all the junk I’ve got strapped onto my bike, I somehow wasn’t smart enough to bring my own shelter.

The next day, I head south to the town of Fox Lake and visit the Metra station, the endpoint of the Milwaukee District North line, emblazoned with a stylized sailboat. Then I roll about ten miles southwest through idyllic scenery of red barns, young corn and soybeans to McHenry, named after politician and military leader William McHenry, who fought Native Americans in the Battle of Tecumseh. It’s also the hometown of my old bike-messenger colleague Matt Skiba, guitarist for the wildly popular punk band the Alkaline Trio.

It’s Father’s Day Sunday and people are lined up at the Riverside Bake Shop on the main street, picking up boxes of their excellent doughnuts. I buy some sugar cookies inscribed “World’s Greatest Dad” for friends who are meeting me down the road in Harvard, Illinois. I visit the local Metra station, then proceed northwest with a sweet tailwind for twenty-one miles to Harvard.

As I roll into town, I’m greeted by a fiberglass cow on a podium that says, “Welcome to Harvard, Home of Milk Day,” which, unfortunately, took place the previous weekend. The festivities included the crowning of a Milk Days queen, prince and princess, an antique tractor display, a milk-chugging contest, and “Cow Chip Lotto.”

Harvard is the terminus of the Union Pacific Northwest line, and the farthest Northwest point in the Metra system, as well as the Chicago region. After a twenty-minute delay, my buddies arrive. Michael is my oldest friend in Chicago—we lived at a hippie housing co-op in Hyde Park together back in 1990—and Jonathan is a pal from the Critical Mass bike ride. Jonathan is, appropriately, wearing his pink Chicago Perimeter Ride t-shirt, featuring images of the Indian, the hotdogs and the sadly demolished Berwyn Car Spike.

We depart for Elgin, the next station destination, with the wind now squarely in our faces. It’s a tough slog with my heavy bike, so my friends are kind enough to act as my “domestiques,” a bike-racing term for team members who block the wind for the star cyclist. As we struggle south, I look up the lyrics to Bob Seger’s “Against the Wind” on my smart phone (dumb move, I know), and holler them defiantly:

Against the wind

We were runnin’ against the wind

We were young and strong, we were runnin’

Against the wind

At this point, a Lexus driver speeds past us, blasting his horn.

We make our way into Elgin on Big Timber Road, stopping to tag the Big Timber Metra stop, the last one on the Milwaukee District West Line. At the Elgin Public House, on the east side of town, we cool off with pints of locally brewed Two Brothers Dog Days Dortmunder-style lager and watch Argentina play Bosnia in the World Cup. Jonathan strikes up a conversation with a young woman named Lindsay, an Elgin native who’s fresh back from studying art with a master painter near Bordeaux, France. She’s planning to teach English in Korea to pay off her student debt.

After bidding farewell to my friends, who are catching the train from the downtown stop, I make my way back west to where I’ll be camping. I pass through neighborhoods on the west side of Elgin, on steep river bluffs, featuring colorful, old Victorian homes.

I spend the night at Burnidge Forest Preserve, a few miles from downtown, a surprisingly pleasant green space. It features a handful of nice walk-in campsites, but when I try to set up in one of the wooded sites, I’m eaten alive by mosquitoes. Instead, I camp in a lovely meadow, where I get a great view of the stars. When you’ve lived for years in a big city where you usually can’t see them, it’s good to get a reminder of their beauty. Besides bugs, the main drawback of the campground is the lack of showers, a must after a hot, dusty ride. I’m forced to take a towel bath in the men’s room stall, wringing out my soapy washcloth over the toilet.

The next morning I pedal nineteen miles southwest toward Elburn, the endpoint of the Union Pacific West line, which runs due west out of the Chicago Loop. On the way, I pass by horse farms, where mahogany-colored stallions trot in fields surrounded by white wooden snake fences. I also pass by brand-new McMansions in locations where it would be virtually impossible to live without a car. It’s depressing to see that suburban sprawl has expanded this far west into what was recently farmland.

Elburn, a town of 5,602 was originally named Melbourne, after the Australian city, but the moniker was shortened over the years. The railroad town has a quaint little main street, including the Elburn Market, an excellent butcher store, where I pick up some biltong, South African-style beef jerky, thick-cut and seasoned with coriander. The Metra station features a flat roof and elongated windows, a nod to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School architecture.

After pedaling east for several miles, I roll into Batavia, another town on the Fox. During the late 1800s, it became known as the “Windmill City” because it was the largest manufacturer of windmills in the world. It was also where Mary Todd Lincoln was committed to a mental hospital after she suffered a breakdown in the wake of her husband’s assassination. Today it’s known for Fermilab, once home to the world’s second-most-powerful particle accelerator, as well as a herd of bison. It's also the town where Streetsblog Chicago's Steven Vance attended high school.

River Street, on the east side of town, is a pleasant semi-pedestrianized block lined with shops and cafes. The sidewalks and roadway are at a uniform height and paved with the same red brick, which blurs the lines between car and pedestrian space, encouraging drivers to proceed with care. A similar “shared street” layout is planned for the New Chinatown retail strip on Chicago’s Argyle Street.

I pick up the Fox River Trail, the mostly paved path that runs over thirty-three miles from Oswego to Algonquin. South of Batavia, on the east side of the river, the trail is hilly and winding, and riding it feels a bit like zooming around the forest planet of Endor from “The Empire Strikes Back” in a cloud car. After this segment ends, I cross a bridge to pick up the trail on the west side, admiring a pair of white cranes fishing at the base of the river’s low waterfall.

Suddenly, in the path ahead of me, I see Gareth, another buddy of mine from Critical Mass, foraging mulberries. A freakishly fit fifty-something, he used to be notorious for biking thirty or so miles from his Logan Square home to suburban bike races, competing, and then pedaling back to the city. I had no idea he was showing up here. He’d sent me several texts during his Metra ride to Aurora, which I’d failed to notice, so it’s a happy coincidence that we happened to cross paths on the trail.

We make our way back to Aurora, the second-most populous city in Illinois with 197,899 people, known as the home of the Hollywood Casino, and metalheads Wayne and Garth from “Wayne’s World.” Conveniently, the local commuter station is housed in the same historic railroad roundhouse as a Two Brothers brewpub.

We admire an old Burlington Route caboose and a Soviet-style statue of a railroad worker outside the roundhouse, and then duck in for some suds. I get my favorite Two Brothers brew, Cane and Ebel, a rye beer sweetened with Thai palm sugar, and we catch a bit of the Iran versus Nigeria game.

By the time we leave, the temperature is in the upper eighties, and sweat is soon oozing out of my pores. As we’re stairstepping toward Joliet in a nasty headwind, Gareth gazes at the farmland and says, “We’re in Illinois now.”

I say, “You mean, it’s weird that the land is slightly hilly but we’re still in flat Illinois?”

“No, I mean, you see barns and fields, and it’s mostly empty. We spend most of our lives in the city and kind of forget that we live in Illinois, in the Midwest. This is a reminder.” I thought back to the old man I met in Kenosha who insisted he was from Vienna, not Austria.

After passing through Plainfield, we ride a stretch of the Lincoln Highway, a southeast B-line to Joliet. Built a century ago, the road was the nation’s first paved coast-to-coast highway, stretching 3,389 miles from New York’s Times Square to Lincoln Park in San Francisco.

Situated on the Des Plaines River, Joliet is yet another large suburb with riverboat casinos. With 148,402 people, it’s the fourth-biggest city in Illinois, and the childhood home of singer Lionel Richie. We stop downtown at Union Station, the terminus for Metra’s Heritage Corridor and Rock Island District lines, and a stop on Amtrak’s Texas Eagle service from Chicago to San Antonio. The station is graced by a statue of Katherine Dunham, the locally raised dancer, educator and activist, who helped introduce African and Caribbean movements into American modern dance.

On the east side of town, we pick up the Wauponsee Glacial Trail, which takes us several miles southeast to Manhattan, Illinois, the southernmost point on my journey, and the endpoint of Metra’s SouthWest Service line. Along the way we see a guy in an undershirt pedaling with a tallboy of Miller Lite in his hand. Further down the path, we see a broken wide-screen TV abandoned in the middle of the trail, and a leaping stag.

As we pull into Manhattan, population 7,093, John Cougar Mellencamp’s “Small Town” is going through my head. Here, at the southern end of what could conceivably be called the Chicago suburbs, we’re still eight miles north of the proposed route for the Illiana Tollway.

This forty-seven-mile, $2.75 billion expressway would run south of the existing metro area, but it would spur development in areas that would be nearly impossible to serve by public transportation, while competing with transit for scarce funding. Governor Quinn and the Illinois Department of Transportation have been pushing hard for this project, which local urban planners have predicted will be a financial and environmental disaster.

Reportedly, this is because Quinn feels he needs the support of South Side and south-suburban legislators in the tough upcoming gubernatorial election. These lawmakers are under the impression that the highway would provide tens of thousands of jobs for their constituents. In reality, it would create a relatively paltry 940 long-term jobs over the next forty years.

I’ve long respected Quinn who, as lieutenant governor, bullied Metra into allowing bikes on board, and served as a seemingly non-corrupt foil to ridiculously sleazy governor Rod Blagojevich. So it’s a bummer to see Quinn pushing wasteful, car-centric projects like the Illiana and the $475 million Circle Interchange Expansion, currently under construction in the West Loop.

Unlike its East Coast namesake, there isn’t much to do in Manhattan, Illinois. We turn around and roll north toward New Lenox, where I’ll be crashing at a cheap motel, since I couldn’t find anyplace to legally camp in this part of the region. After fighting the wind for the last several hours, we’re rewarded with a glorious tailwind that pushes us the ten miles to our destination in a flash. I escort Gareth to the local Metra station and thank him for his companionship. This grueling day would have been much less tolerable without it.

Last month, the real estate blog Movoto.com rated New Lenox the most boring town in Illinois due to its lack of young adults, nightlife and music venues, plus its high percentage of fast-food joints. As I survey the monotonous array of chain stores along the Lincoln Highway, that seems to be an accurate assessment.

Refreshed after a night not spent sleeping on the ground, I get on the Old Plank Road Trail, a stone’s throw from my motel. There are plenty of people out recreating on this Tuesday morning, and it’s no wonder. The trail has awesome scenery, with frequent views of marshes populated by blue herons.

At Cicero Avenue, I cut south for a few miles south again to tag the University Park station, one of the termini of the Metra Electric District line. Heading northeast again, I travel through the blue-collar, racially diverse suburb of Chicago Heights, population 30,276.

Continuing northeast to pick up the Burnham Greenway, I’m tempted to cross the Indiana border into Munster to visit Three Floyd’s Brewpub, only a few miles away. In a rare display of self-discipline, I soldier on instead. After riding the trail for a few miles, I come to Sibley Road in Calumet City, where I see the sign for Castaways Bowl, a buccaneer figure, perhaps forty feet tall. It’s a textbook example of postwar “Googie” commercial architecture, a populist school of design that’s near-and-dear to me.

From there, I take Burham Avenue north over some railroad tracks, then descend into Chicago’s Hegewisch neighborhood. I roll past Wolf Lake, a former Nike missile site, where guys in straw hats fish in the sunshine, then pick up the Chicago stretch of the Burnham Greenway.

After that trail peters out, I stop at Calumet Fisheries, located on 95th Street, just west of the bridge over the Calumet River that Jake and Elwood jumped in “The Blues Brothers.” Following an al fresco lunch of scrumptious smoked shrimp, I continue to the 93rd Street commuter rail station in the South Chicago neighborhood, the other terminus of the Metra Electric District line.

At 71st, I get on the Lakefront Trail and pass by the South Shore Cultural Center, where the Chicago Police Department’s horses are stabled. At 67th, the southeast corner of Jackson Park, I catch my first glimpse of the skyline. There’s a lovely, cool breeze coming off the lake, which makes me feel like I’m cruising along on a yacht. North of the 31st Street Beach, the shoreline is packed with revelers barbecuing, playing ball and sunning themselves on blankets.

I’ve lived in this city for a quarter of a century, and at times it can be challenging to keep things fresh. However, as I roll past Grant Park, enjoying an inspiring view of the Michigan Avenue cliff, I get the same feeling I do every time I approach the Loop from the south after being away on a journey: Chicago is a pretty cool place to live.

After I reach my finish line, the Cultural Center, I drop a few frogskins in the tip jar of a New Orleans-style brass trio playing on the corner. After showering at the offices of FK Law, friends of mine [and Streetsblog Chicago Sponsors] who specialize in bike-crash cases, I pedal to a bar in River North where Streetsblog is co-hosting a meet-and-greet with bike/ped planning guru Mia Birk.

Mia served as bike coordinator for Portland, Oregon, from 1993 to 1999, a pivotal time in that city’s transformation to a cycling Mecca. She currently leads the transportation consulting firm Alta Planning + Design, as well as Alta Bicycle Share, which runs the Divvy bike-share program for the city of Chicago. She recently published the memoir “Joyride: Pedaling Toward a Healthier Planet” about her adventures pushing pedaling.

Over drinks, I tell Mia about the epic voyage I have just completed. “The purpose of the Metra-Politan Perimeter Ride was to comprehend just how big the region is,” I say. “It definitely feels massive. Some of the issues that became apparent on my trip were the lack of connectivity between the different commuter lines, and the fact that there’s a lot of new development that’s nowhere near transit. It was interesting to compare the wealthy North Shore with the working-class Southland. Traveling at bicycle speed was a good way to experience these nuances.”

Mia takes a sip of her chardonnay, ponders my comments, and nods her approval. “Being on a bicycle is truly the best way to experience any community, and really see and feel and taste it,” she says with Yoda-like wisdom. “You have truly moved at the speed of humanity.”