On Monday the Chicago Sun-Times noted the large uptick in pedestrian fatalities in 2012 compared to the three years prior. Last year, 48 pedestrians were killed by drivers in Chicago, compared to 35 in 2009, 30 in 2010, and 31 in 2011. Understanding the underlying causes is difficult: Right now, there is troublingly little information from the Chicago Police Department and the Illinois Department of Transportation about why pedestrian deaths rose last year.

Potential culprits include cheaper gas, higher driving rates nationwide, and a milder local winter. But these are only guesses. And while it's easy to track fatal crashes (they're reported by news media), data on injuries – a better overall gauge of street safety – won't come out until August 2013. If Mayor Emanuel and Transportation Commissioner Gabe Klein want to eliminate traffic deaths by 2022, the methods of collecting and distributing data on traffic crashes and causes of injuries need to be improved.

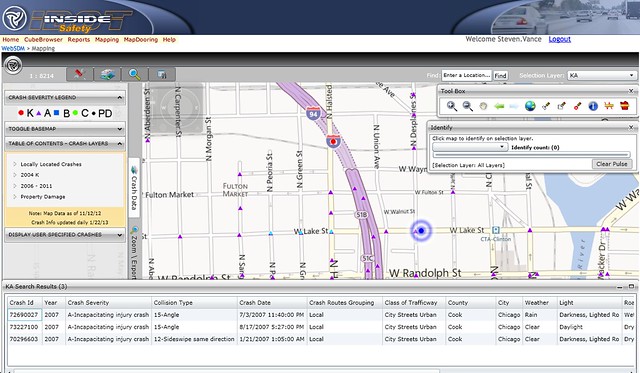

Publication of the crash data in a more timely manner and with greater detail would improve understanding of underlying causes. The way things stand, information about traffic injuries and deaths is not easily accessible to public officials (including aldermen), street safety advocates, or the public at large. The Illinois Department of Transportation's Safety Data Mart is open to the public, but it's slow, has a tedious interface, and omits crash locations (except for dooring incidents, but that feature has been broken for over a month). Simple things like picking a date range to search are far from intuitive. And the Safety Data Mart provides aggregated data about drivers, passengers, and pedestrians, but not bicyclists.

Another problem is that the system for gathering information on traffic crashes has a car-centric structure that puts street safety advocates at a disadvantage when trying to understand causes. Amanda Woodall, a policy expert on crash reporting at the Active Transportation Alliance, explained where there are gaps in the process. "If the idea behind collecting crash data is to understand why they are caused and how to prevent them, we need to understand as much as possible," she said. "There are two things that prevent us from doing that."

First, she said, the IDOT crash report form doesn't allow the responding police officer to assign descriptive collision types ("angle," "sideswipe") to pedestrian or bicycle crashes (view an example). Only car-on-car crashes get that level of detail.

Instead, when responding officers tick off the box on a crash report form that a bicyclist or pedestrian was involved, they're required to describe the scenario leading up to the crash on the back of the form. But relying on the narrative can get in the way of understanding what happened. "Was the bicyclist going the wrong way, or the right way?" said Woodall. "Were they hit from the side because someone pulled out of a driveway? You shouldn't have to read the narrative to be able to categorize."

Second, IDOT has thresholds that must be met before they will include a given crash in their dataset. In 2009, IDOT only put crashes resulting in injury or at least $1,500 in property damage in its dataset.

"There are many bicycle crashes that occur where no one is injured and there isn't $1,500 in property damage," Woodall said. She argued that all crashes should be reported, regardless of the level of destruction caused. "We don't report things because they cost money, we report things because they endanger safety."