McCoy Cantwell was born and raised in Chicago and now live in Los Angeles, where he's pursing a master's degree urban and regional planning at Cal Poly Pomona. He wrote this piece as a class assignment to discuss a current planning issue.

In true egalitarian ethos, architect and urban designer Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago ambitiously proclaimed that "the Lakefront by right belongs to the people… not a foot of its shores should be appropriated to [their] exclusion."

Less than two decades earlier, Burnham conceived of and oversaw the transformation of southern Hyde Park into the White City fairgrounds for 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. His Plan of Chicago statement referred to the city's 26 miles of Lake Michigan coastline. And in accordance with Burnham’s exhortation, today, almost all of the lakefront is public park space.

While almost all of the land immediately next to the water is open for all to use, eight-lane DuSable Lake Shore Drive snakes along most the shoreline. The higheway creates a loud, chaotic, and dangerous barrier between the city’s neighborhoods and its most precious natural resource.

For more than a decade, the Illinois and Chicago transportation departments have led the Redefine the Drive project to redesign the road on the city's North Side in advance of a rebuild. Last June, the agencies recommended reconstructing the highway largely in its current state to appease car drivers, and rejected the possibility of creating dedicated transit lanes.

However, a recent push from sustainable transportation advocates and elected officials could help lead to a repurposed, more equitable DLSD that connects more people to Chicago’s lush lakefront.

The creation of DuSable Lake Shore Drive

When Burnham was developing his plan for the city in the early 1900s, DuSable Lake Shore Drive was little more than a boulevard through shoreline parkland. (While the highway was long simply called Lake Shore Drive, in 2021 it was renamed for trading post operator Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable, considered to be the area's first permanent non-Native settler.)

In late 1800s, dry goods and department store magnate Potter Palmer had built the first stretch of the road for two reasons: to protect his Gold Coast mansion from the tides of Lake Michigan via a seawall, and to create a relaxing route for him and his wealthy friends to ride their new carriages down the coast.

Along with landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s expansion of Chicago's parks in the 1890s for the World’s Fair, the lakefront road was extended south to connect with Hyde Park, which was at the time accessible to downtown by train and cable car. Further park development north of Palmer’s estate brought northern expansion of the drive. By the 1950s, when personal automobiles became more affordable for working-class people, the full roughly 15-mile stretch had been built.

In the years since DLSD’s creation, infill development on the lake extended public parkland on the shore. Nowadays, only a handful of buildings sit on the east side of the highway, which are almost entirely used for recreation. These include Navy Pier, the Museum Campus, and a small portion McCormick Place.

An aging barrier to Chicago parks and recreation

Chicago’s two dozen sand beaches and the 18.5 mile running/biking path — the Chicago Lakefront Trail — are beloved additions to the shore, frequently used as recreation sites for residents and visitors alike. During the summer months, when punishing heat and humidity send Chicagoans running for temperatures cooler by the lake, the lakefront parks are filled with countless residents and visitors, organized sports, formal events and gatherings for barbecues and parties. But, along the entire northern seven miles of DuSable Lake Shore Drive, only 22 crossings are open to non-auto users; of these, the majority are inhospitable over-road bridges or poorly lit, damp, and often smelly under-road tunnels.

As it currently stands, DLSD suffers from more than just infrastructural woes; its presence as a physical and psychological barrier is backed up by safety data and pollution measurements. During peak hours, the road is mercilessly congested, including for the many express buses stuck behind cars. When congestion is low, another worrying pattern emerges – a road marked between 40-45 miles per hour speed limits is designed for speeds much higher, and speeding and reckless driving abound.

Taking into account roads and ramps leading to or away from the Drive, the road contributes to 7.9 crashes and 1.9 injuries per day. From 2019 to 2023, 49 people were killed, according to data analyzed by safe streets activist Michael McLean and reported by longtime former Chicago Tribune transportation writer Mary Wisniewski.

Recognizing the road’s age (with much of it nearing 100 years old), its dangerous existing conditions, and its impact as a barrier between Chicagoans and the lakefront, a joint project study group was created in 2013 under the name Redefine the Drive. This task force is composed of five organizations: the Illinois Department of Transportation, the Chicago Department of Transportation, the Federal Highway Administration, and the Chicago Park District, with the Chicago Transit Authority operating in an advisory capacity as a major stakeholder.

Reimagining DLSD within the Complete Streets vision

The ambitious undertaking is based on a purpose and need statement calling for improved safety and mobility for all users, greater circulation and access along the corridor, and remedying infrastructural deficiencies. Though not listed as a key concern when the project group was assembled in 2013, advocates and local politicians have also expressed a desire that the Drive’s redesign would have a tangible climate impact, both in removing emissions from the road via fewer solo car trips and in protecting the infill shoreline from rising water levels and historically severe storms.

Chicago is also busy expanding its bike network in an effort to make the city safer for all users and cut down on carbon emissions.

As of 2013, the Chicago Department of Transportation adjusted its Complete Streets policy to prioritize (in order) pedestrians, public transit, bicycles, and autos. Little by little, parts of the city have enjoyed expanded sidewalk space and pedestrian amenities, bus priority lanes, neighborhood low-stress bikeways and protected lanes on major streets, among other projects. CDOT has also explicitly set medium-term goals to reduce citywide carbon pollution and double transit ridership.

The Lakefront Trail, while an incredible amenity for bicyclists, is primarily a recreational route; bike commuters cannot, in its current configuration, use the more direct DuSbale Lake Shore Drive to get downtown and into neighborhoods quickly. And according to the results of IDOT survey conducted as a part of the initial outreach for Redefine the Drive highlighted by Ted Villaire of the Active Transportation Alliance, 60 percent of road users that drive on the northern portion of the Drive would prefer to take transit if it were more reliable and frequent — both qualities stymied by its existing, car-dominant, congested state.

IDOT’s disappointing reveal

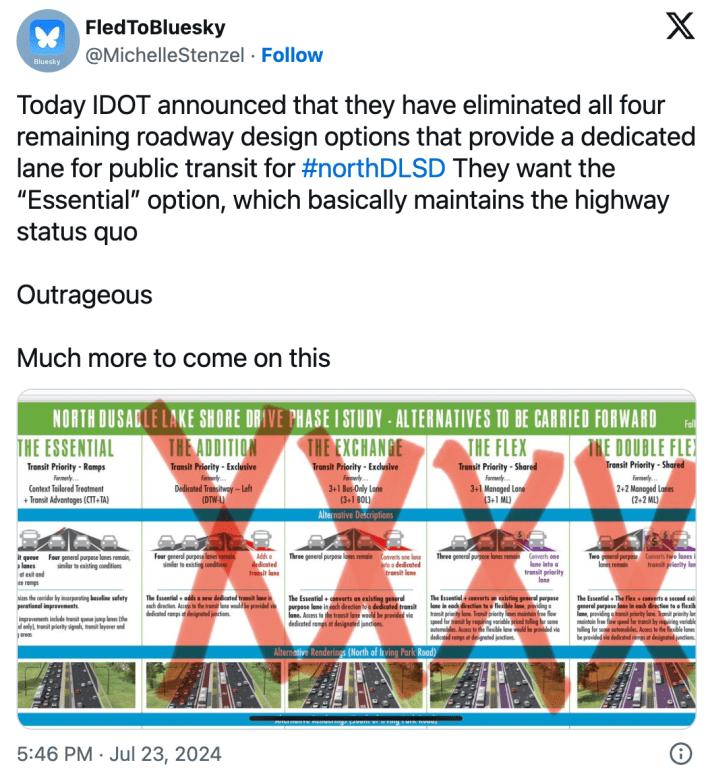

Ten years after the study began, there was much excitement over the transformative promise of the project and Chicagoans were eager to see the proposal brought by the Redefine the Drive task force. However, this excitement quickly turned to outrage once IDOT revealed their plans last summer.

Under IDOT’s preferred alternative, DuSable Lake Shore Drive would be widened, major street-Drive junctions would be redesigned to facilitate greater automotive throughput, and the “S curve” by Oak Street Beach and downtown would be softened (which would both allow for increased speeds and virtually eliminate the possibility of Lake Michigan storm surges reaching the road, as they currently do).

The only transit benefits promised under their proposal are bus priority entry and exit lanes off the highway. And to IDOT’s credit, there are a couple of major benefits proposed — specifically that the massive lakefill effort required for the softening of the “S curve” ends up adding more than 80 acres of new public beach and parkland, and the road improvements are estimated to lower commute lengths by 5-7 minutes.

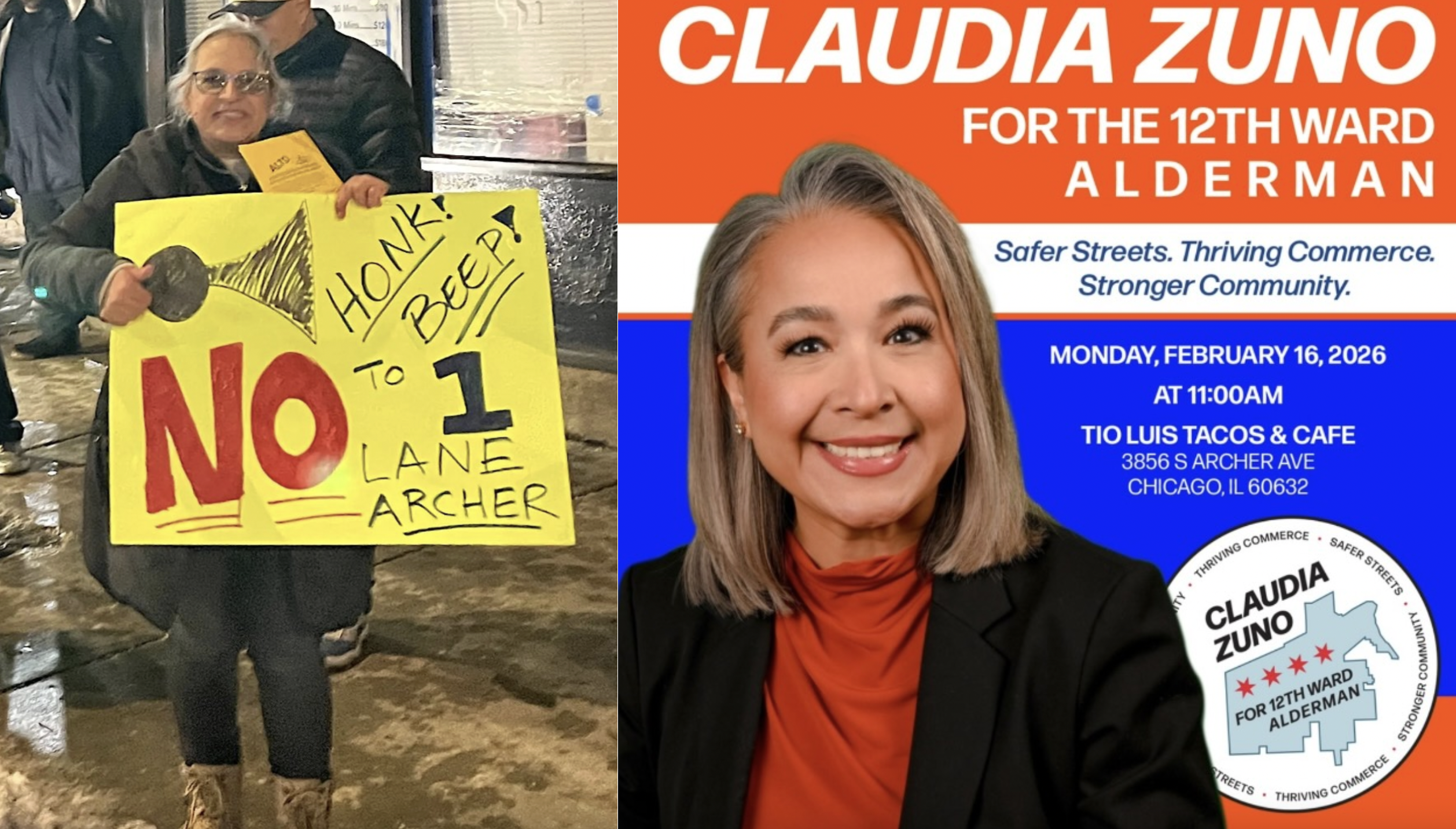

Hundreds of activists, furious residents, and local politicians sprang to action, with the “Save Our Lakefront” rally materializing within 24 hours of IDOT’s announcement. Chicago aldermen with wards that would be affected by the redesign have been critics for longer, having previously written to IDOT and CDOT demanding a halt to the project and a “modern” reimagining of the road, prioritizing “non-car travel and put[ting] pedestrians, cyclists, public transit users, recreation, green space, commercial growth, and property values ahead of rapid private passenger vehicle movement”.

Taking action at the ground level (and in the State Capitol)

These aldermen, alongside transportation experts and advocates, have called for the Drive to include bus rapid transit and dedicated bus lanes at a minimum, and potentially a lakefront light rail system. At the rally, 1st Ward Alderperson Daniel La Spata insisted that “we can have our cake and eat it too,” he explained. “We can have more green space and bus-only lanes. We can have safer streets and a boulevard feel…But that’s only if in this moment we have the courage to demand better.”

To their point, better alternatives have been proposed than one which keeps and speeds up the already-dangerous highway. Chicago-area representatives to the Illinois House of Representatives and Senate both introduced resolutions in support of a “creative and forward-thinking” redesign that turns the roadway into a “true boulevard”. State Representative Kam Buckner, who introduced the resolution in the Illinois General Assembly, told reporter Mary Wisniewski last summer that “having the Autobahn next to the lakefront is a problem” for him.

A letter from transportation and environmental advocacy organizations was addressed to IDOT, insisting that – among other demands – the project be restarted with Chicago’s Department of Planning and Development (who had been left off the original task force) at the helm; the project support existing city and regional transportation and climate goals; and the stakeholders commit to an accelerated timeline to prevent another decade of planning.

Focusing on a true, equitable reassessment of DLSD

One of the chief reasons to restart the effort is that the purpose and need of such a redesign of DuSable Lake Shore Drive has changed since its inception 11 years ago.

Jim Merrell, a spokesperson for Chicago’s Active Transportation Alliance, sees the initial visioning language as the “original sin” of the project, he told Wisniewski.

“The purpose and need of the project basically says we need to make the roadway better for everyone, including people driving by themselves in a car,” he explained. “This shapes the problem the engineers were given to solve. Anything that slows down private cars was dinged in their analysis.”

Under this paradigm, innovative plans to reimagine the Drive as a multimodal boulevard — or simply shift existing lane priorities — cannot be seriously considered since they take cars off the road to improve conditions for non-automotive lakefront users. This roadblock exists despite IDOT’s own findings that 60 percent of drivers would prefer taking transit options if they were faster and more reliable.

According to the official DuSable Lake Shore Drive website, the busy arterial road sees as many as 155,000 cars and 69,000 CTA bus travelers each day while the Lakefront Trail can have as many as 25,000 users each day during the warmer months. A visionary reimagining of the Drive could slash the number of drivers if they were better served by speedy transit options or felt safer biking.

Roberto Requejo, a board member of the CTA, sees IDOT’s car-centric proposal as “a continuation of bad planning, bad engineering from the 20th century and something that is going to damage our city on an environmental level.” Imaginative urban planning and design should be inserted here, with a prerogative to remove vehicles off the road, improve multimodal options on this critical corridor, and reconnect residents to their beautiful lakefront.

Did you appreciate this post? Streetsblog Chicago is currently fundraising to help cover our 2025-26 budget. If you appreciate our reporting and advocacy on local sustainable transportation issues, please consider making a tax-deductible donation here. Thank you.