Update 12/21/23, 1:15 PM: In response to this article, Ald. Vasquez stated on Twitter that, since the goal of this project is improved safety, the 40th Ward and CDOT will continue monitoring the reversal of the 4800 block of North Francisco Avenue. They'll keep an eye out for any new issues that may arise at the intersection of Frnacisco and Aislie avenues, such as the potential for head-on collisions, which some constituents have voiced concern about. If deemed necessary, the ward and CDOT will potentially make changes to the design, such as reversing the direction of this block once again.

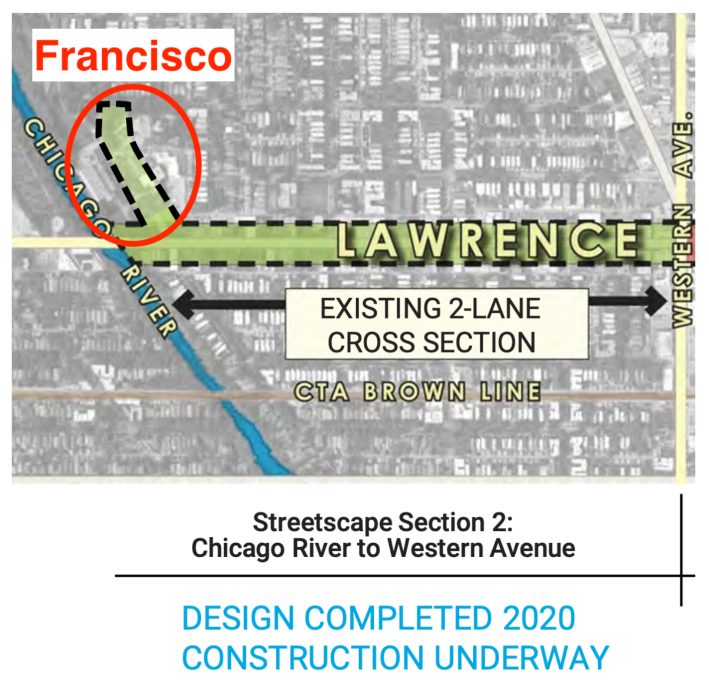

Last week Ald. Andre Vasquez (40th) and the Chicago Department of Transportation held a meeting at the Lawrence Hall home for at-risk youth to discuss street design changes in the Mid-North Side ward. The focus was on a piece of the Lawrence Streetscape project, a project whose goal is to bring safety and beauty to Lawrence Avenue (4800 N.) between Western Avenue (2400 W.) and the Chicago River (3000 W.)

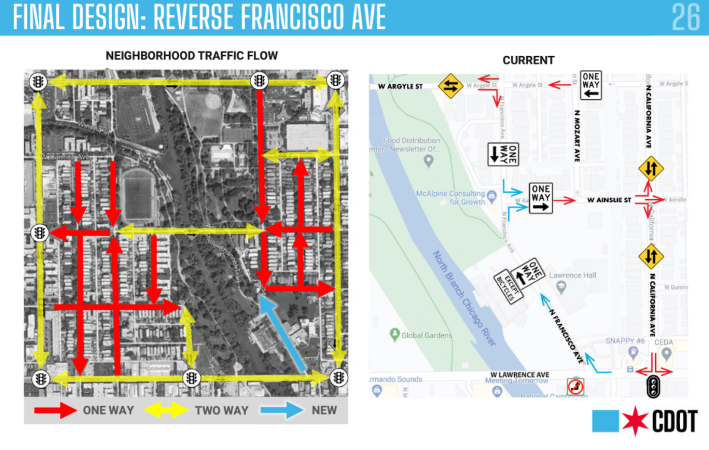

On the northwest corner of the project area is a one-block stretch of Francisco Avenue (2830 W.) between Lawrence and Ainslie Avenue (4900 N.) that is a frequently-used access point for pedestrians, bike riders, and other non-drivers going to River Park and the North Branch Trail. And while Francisco should be a quiet, residential street, it is also frequented by southbound drivers using it as a "cut-through route" to avoid congestion on nearby California Avenue (2800 W.) As part of the Lawrence Avenue project, CDOT is reversing this one-block section of Francisco to one-way northbound.

While the meeting was scheduled to end at 6:30 p.m. residents were still providing feedback as late as 8 p.m. The meeting room was full and buzzing, with 50 people there before things even began. Kara Teeple, the CEO of Lawrence Hall commented, "In all my years of hosting community [Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy] meetings, I’ve never seen something so well attended."

The hearing began as many community meetings do, with a soft-spoken presentation on the project scope and background. Attendees learned about the broader project, and then heard more about the specifics of this particular piece and the various considerations that got the planners to their eventual decision.

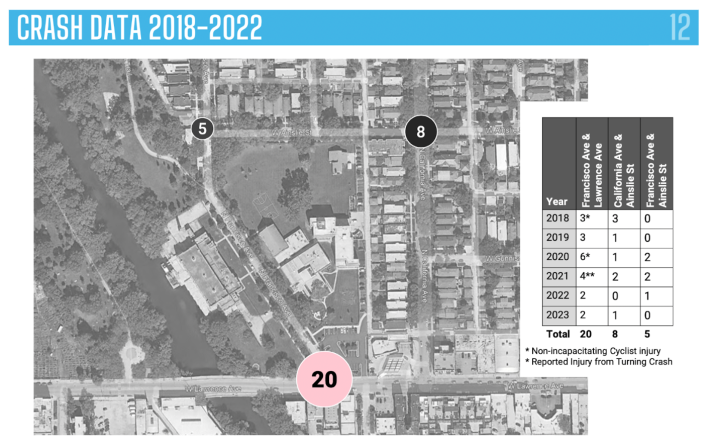

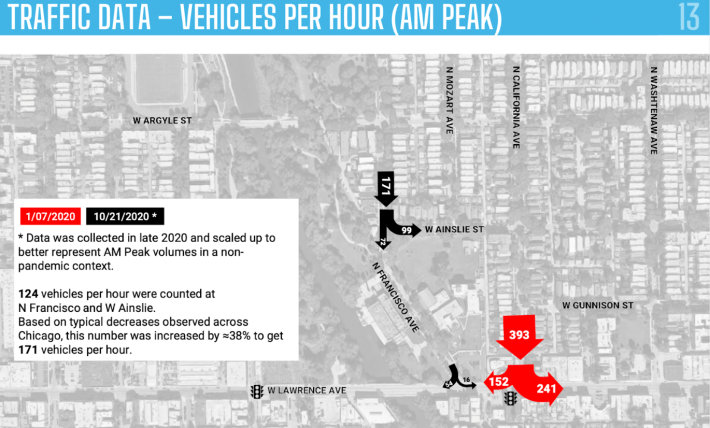

Poignant in the data presentation were traffic volumes and crash data. In the five-year traffic study period, 25 crashes were reported at either the intersections of Francisco and Ainslie or Francisco and Lawrence. Furthermore, an astounding 171 vehicles per hour were recorded traveling through the Francisco and Ainslie intersection during peak morning periods. At nearly three vehicles per minute, this corresponds to my previously reported direct observations of 51 motorists in 15 minutes during a recent afternoon rush period.

"While [cut-through traffic] might seem reasonable to drivers who want to avoid traffic, residential streets are not set up for this kind of activity," stated Allison Murphy, Ald. Vasquez's director of communications and development, in a post-meeting email. "Cars speeding down residential streets to avoid traffic present a danger to pedestrians, especially on streets with parks and schools like Francisco."

Once the presentation ended, the meeting moved on to a Q&A. Opponents of this plan, predictably, dominated this portion of the meeting. The questions they asked, however, were a case study in antiquated, entitled, motorist thinking. Each time opponents seemed to present a question as though it was an obvious indictment of the project, Ald Andre Vasquez and other 40th Ward and CDOT staffers showed them that this was a feature, not a defect, indeed the reason for it to exist in the first place.

While Ald. Vasquez had previously suggested that he might cancel the street direction reversal, in this meeting, Ald. Vasquez cemented his status as one of the leading safe streets advocates in City Council. In few, if any other, occasions has an alderperson so powerfully and clearly articulated the value of safe streets, and the change in thinking required to achieve them. Furthermore, this was not a moment of abstract grandstanding. It was a difficult conversation with unhappy constituents. They refused to accept that sometimes street safety means drivers don't get to move super-conveniently through neighborhoods.

The biggest point of contention in the evening was the purpose of the project: eliminating a beloved motorist cut-through route. Early in the meeting a very vocal opponent said, “We should remove the word 'cut-through' from our vocabulary. What does this even mean? These are city streets." The attendee maintained the common motorist attitude that they should be able to drive wherever they want, on any street, as quickly. "We are taxpayers and these are our streets," she shouted. Ald. Vasquez may have known there was at least one parent in the audience who had lost a child to traffic violence, and he did not hold back, "There are crashes happening along these streets, and they belong to those victims just as much as you."

In a pattern of grasping desperation, the opponent switched to another tack, and oriented her questions towards standard, sky-is-falling comments about what will happen to existing traffic. "By doing this you will direct all of this traffic onto California!" she said.

Ald. Vasquez responded, “Yes, that’s the purpose of California, to collect traffic from the residential streets.”

"But California is slow,” the constituent continued, “We will have to drive so slow!"

Demonstrating impeccable mastery of modern safe streets thinking, Andre didn’t miss a beat, "Slow cars have a much harder time hurting people than fast cars do, and this is primarily about safety."

Once again the opponent changed arguments, and started highlighting other bad motorist behavior, as if it would somehow convince Vasquez's team to open back up the shortcut. "There are lots of crashes further north on Francisco, what will this do for that?"

Ald. Vasquez was once again prepared, "We are adding speed humps to those other areas."

Doubling down, the neighbor said, "Drivers have taken to speeding through the alleys! What will you do about that?"

The opponent couldn’t come up with a potential problem Ald. Vasquez and CDOT hadn’t considered. "We are looking at adding speed bumps to the alleys," he said.

An interesting dynamic to this meeting was that opponents didn’t suggest that the project had missed some important detail. Over and over again, opponents criticized the plan for being likely to do exactly what it was designed to do, namely, move drivers out of the neighborhood. Every step of the way the team had answers, and they could go deep into detail. At one point, they spent 15 minutes on the bi-directional bike lane and the many factors considered in its placement.

By the end of the meeting, the 40th Ward and CDOT staffers were visibly drained. At first glance, this seemed odd, because they conducted themselves like world class safe streets advocates. Ald. Vasquez was bold, calm, and well-reasoned. His team was also effective. Early on, as Allison Murphy framed the project as firmly rooted in safety, she seemed almost to choke up. "We have lost too many neighbors to traffic violence, children have been killed in car crashes during our administration, and that weighs heavy on our hearts."

It was an impassioned appeal to a room brimming with drivers who wanted nothing more than to be able drive fast past a park. It seemed like they had no empathy for victims, or the survivors who sat silently among them. No matter what talk of safety came up, for the drivers it came down to, as it always does, “Yes I get that, but do you understand I’m losing my ability to drive conveniently."

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.