Bus rapid transit, upgraded bus service that approaches train speeds for a fraction of the cost of installing rail, has increasingly been on the lips of transit advocates. Between the upheaval of commute patterns since the pandemic and ever-worsening car congestion, BRT is one cost-effective solution to shortening travel times on transit and encouraging more people to make the switch to public transportation. The CTA drafted a plan for BRT on Ashland Avenue in 2013, but the project was quashed due to lack of political will and car-centric backlash.

Olivia Gahan is a member of Commuters Take Action (CTAction), a grassroots transit advocacy group that formed in response to worsening service and inaccurate CTA arrival schedules. CTAction, along with other local advocacy groups including Active Transportation Alliance, is breathing life back into Chicago's BRT conversation. I spoke with Gahan about how BRT could transform public transportation in Chicago and what it will take to make it happen.

This interview has been edited for clarity from two conversations.

Sharon Hoyer: Why is bus rapid transit a priority for Commuters Take Action?

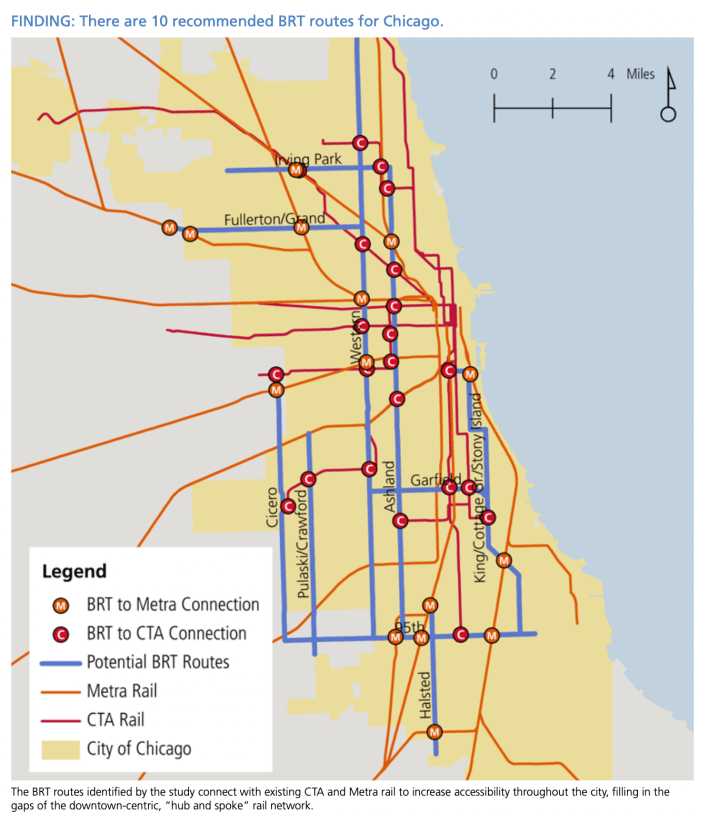

Olivia Gahan: BRT is a priority for Chicago for so many reasons! First, bus ridership has remained the top transit choice for riders during and post-pandemic. Adding rapid bus transit will help the CTA organization continue to retain and grow ridership numbers. Transit patterns have changed in Chicago and having downtown-centric transit doesn't reflect the movement realities of Chicagoans. BRT will also provide much-needed rapid north-south transit to expand beyond the east side. These new BRT routes are also cheaper to build than new rail lines, costing only one third of constructing a new rail stop. The realities of living in the midst of climate change demand changes to transit. First, BRT lines will reduce the use of personal vehicles; the 2012 BRT feasibility study found that the proposed Ashland route will add at least 40,000 additional transit trips. Adding three routes—Ashland Avenue, Western Avenue, and 95th Street—would increase overall transit trips. BRT routes can be outfitted with electric fleets, a move that aligns with the CTA's and RTA's zero emissions plan.

SH: What does the buildout of BRT entail and how do you come to the one-third-cost-of-rail number?

OG: That figure came from a 2011 study from the Metropolitan Planning Council. This report was foundational but then kicked off the formal study the CTA did of Ashland Avenue in 2013. It’s kind of my bible when it comes to BRT. This is the cost of creating greenways along a BRT route, building out [prepaid] boarding stations that people swipe to enter instead of swiping when they get on the bus. This would also include protected lanes for buses that keep cars out of the BRT lane.

[In 2018, the CTA estimated that the 16-mile Ashland BRT route would cost $160 million. The Wilson 'L' station renovation, completed the same year, cost $203 million.]

SH: In the BRT literature, I’ve seen that, along with dedicated lanes and off-board fare collection, buses travel faster due to less frequent stops.

OG: Yes, the average space between stops would be a quarter to a half mile. You could imagine, say, the space between Ashland Express bus stops being built out as BRT stations.

SH: I take it buildout of BRT lanes entails coordination between ward alders and the agencies that own the roads—the Chicago Department of Transit, the Illinois Department of Transportation, and Cook County. So, getting cross-town rapid bus service is probably as complicated as getting a connected bike network?

OG: [laughs] Yes. In addition to grassroots support, we’re going to be collecting signatures of support from surrounding businesses. There’s increased economic potential around BRT stations.

SH: [The Regional Transportation Authority, which oversees regional transit] and CTA have both expressed support for BRT in their most recent strategic plans, and Mayor Johnson's transportation subcommittee has included BRT development in their recommendations. How do you see this influencing on-the-ground implementation of BRT?

OG: This is the best-case scenario for raising grassroots awareness and support! We hope to garner a massive show of support for this effort through community education, demystifying the process of working with public officials, and providing people with tools to bring change to their transit systems.

SH: What are the impediments to BRT being adopted in Chicago?

OG: The greatest impediments are officials applying for funding, car-centric urban planning, and lack of knowledge and education about BRT's benefits. CTAction can't apply for grant money but we can share information about the possibilities of BRT routes to build grassroots support for modern, equitable, and rapid transit.

A lackluster legislative body is also to blame. While transit and BRT have a few key champions in City Council, which we are happy to see, we have seen little evidence of initiative from the Committee on Transportation and Public Way, the committee that "has jurisdiction over all matters relating to the Chicago Transit Authority, the subways and the furnishing of public transportation within the City." We hope to see this Committee's chairperson, Ald. Gregory Mitchell (7th), prioritize BRT by taking steps like putting BRT on their committee agenda and calling for a BRT feasibility study.

A lack of voter awareness about the benefits of BRT may also contribute. We hope to build grassroots support for BRT by sharing our vision of how it would connect Chicago: imagine being able to go by bus from Pilsen to Andersonville in 30 minutes instead of more than an hour, or from Auburn Gresham to McKinley Park in just 20 minutes, instead of 40? This is the level of connectedness that BRT would enable.

One of the greatest impediments is a lack of initiative from the CTA to apply for funding. The federal government has recently awarded cities like Minneapolis/St. Paul more than $239M in [BRT] funding, which will be instrumental in helping them construct their Gold Line BRT project. We are unaware of any current initiative by CTA to apply for BRT funding. Before applying for funding, the CTA would need to complete a feasibility study, which we have not seen any movement on either (aside from the one completed more than a decade ago for the failed Ashland BRT project.)

SH: Why have there been no BRT feasibility studies since the failed Ashland Avenue project?

OG: That’s a great question. I have a hypothesis, but I don’t know that it’s the correct answer. I don’t think there’s enough education about what BRT stations could mean to the communities they would be in, and not enough grassroots support to bring it in. This is our immediate call to action—for a new feasibility study to take place. We are currently in the planning phase, with a heavy focus on creating educational materials for chambers of commerce, neighborhood groups, and alderpersons along Ashland, Western, and 95th. Concretely, we are putting together a call-to-action plan, calling for an updated feasibility study for BRT!

The way the city travels since COVID has been markedly different, so I think this makes it the perfect time to bring it up again. A lot of us are more remote now and the need for rapid north-south transit outside the Red Line is more highlighted now.

SH: How can people get involved to advocate for BRT?

OG: CTAction is still collecting surveys for people to report their feelings on BRT. In the coming months we’ll be putting out a toolkit for connecting with alderpersons, CTA and CDOT.

SH: Anything else you’d like to mention?

OG: We’re not the only people working on this. There are four organizations working for BRT and this will ultimately be a coalition effort.

Take the Commuters Take Action Bus Rapid Transit survey here.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.