Traffic violence is a critical public safety issue in the United States. In 2021 alone, drivers killed about 42,915 Americans, the most since 2005. In the first quarter of 2022, 9,560 people died in traffic crashes, the most since 2002.

But these numbers should not come as a surprise. In 2020 when the number of car trips dropped during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic reducing traffic congestion, overly wide American roads designed to prioritize vehicular throughput above all else suddenly felt like speedways. Even now that the crisis has eased and traffic volumes have returned to normal, fewer people are commuting to downtown offices, which means fewer rush-hour traffic jams and higher speeds overall, which has fueled the spike in road deaths.

Chicago is no exception to this trend. Last year local traffic fatalities spiked to 174 deaths on city streets. As many have observed, if these statistics were applied to any other form of transportation like trains or airplanes, swift and decisive action would be taken to improve safety. But, as director of Transportation for America Beth Osborne noted, when private car drivers kill people, it's often chalked up as “the cost of doing business.”

Vulnerable road users like pedestrians and cyclists have been disproportionately impacted by the increase in dangerous driving. Between 2020 and 2021, there was a 10.5 percent increase in traffic fatalities overall. But pedestrian deaths rose 13 percent in 2021 from the previous year. And bike crash deaths spiked by 16 percent in 2020 compared to 2019, and then rose another 5 percent in 2021.

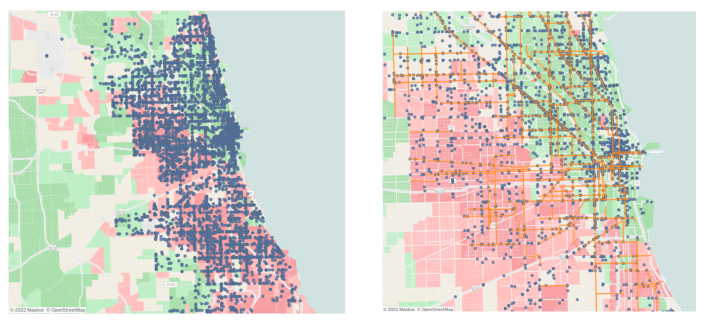

This summer alone, motorists have struck and killed at least seven Chicagoland children on foot, scooters, and bikes. In order to better understand this public safety crisis, I created a Tableau story mapping out where recent pedestrian and bike crashes have occurred in Chicago. I also tried to gauge how effective or ineffective existing infrastructure is at keeping vulnerable road users safe.

First, it’s important to understand the magnitude and scale of the problem. My maps of locations where drivers have struck people walking and biking in Chicago since 2020 show that no parts of the city were spared from these collisions. It's notable that the bike crashes strongly correlate with city-designated bike routes. That's not surprising, since these are the corridors that have the most bike traffic. But it also suggests that the bike infrastructure that currently exist on these routes isn't sufficient for protecting bike riders.

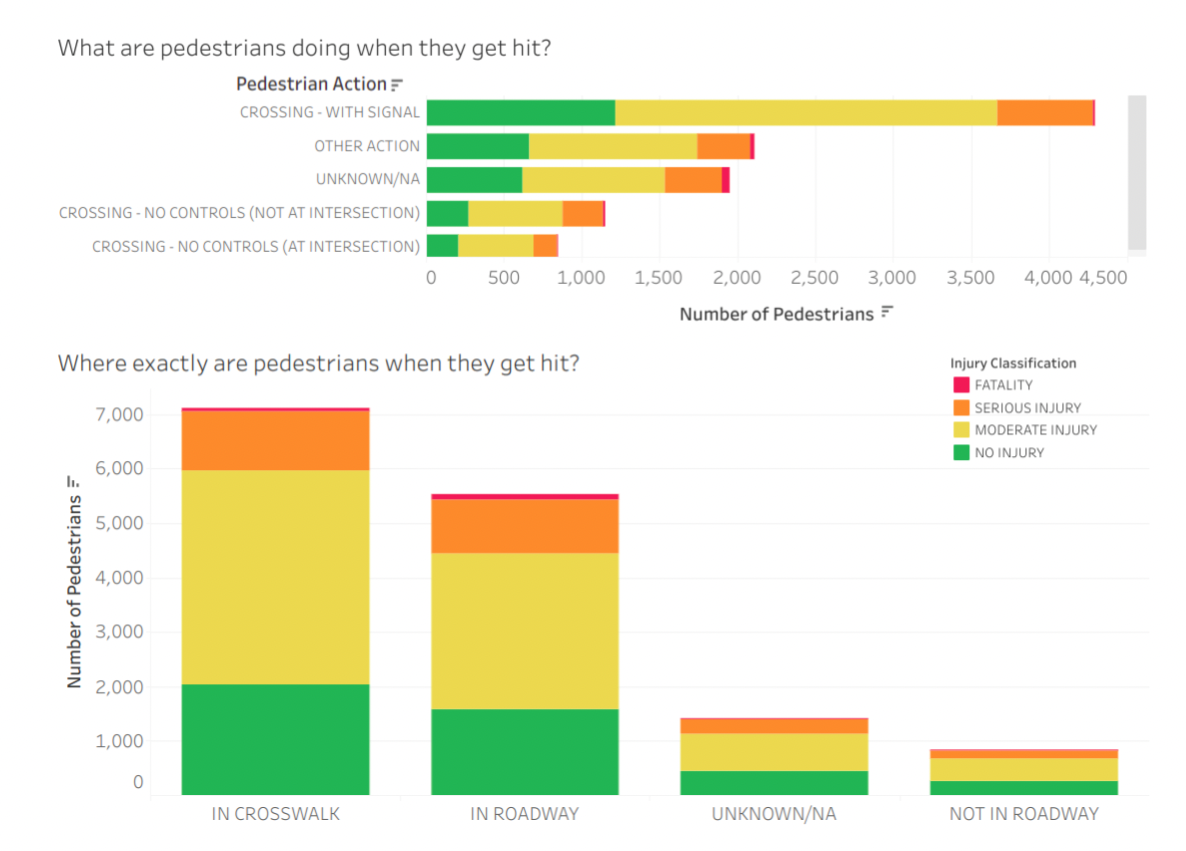

Those who oppose reallocating space on the road from lanes for driving and parking cars to pedestrian and bike infrastructure often dismiss the current safety problem by blaming crash victims. They argue that the struck person was behaving irresponsibly or dangerously, often invoking cliches about pedestrians wandering carelessly into the road, glued to their phones, or cyclists weaving in and out of traffic. In reality, the data shows that most people hit by motorists while walking were behaving lawfully, crossing with a walk signal in a crosswalk.

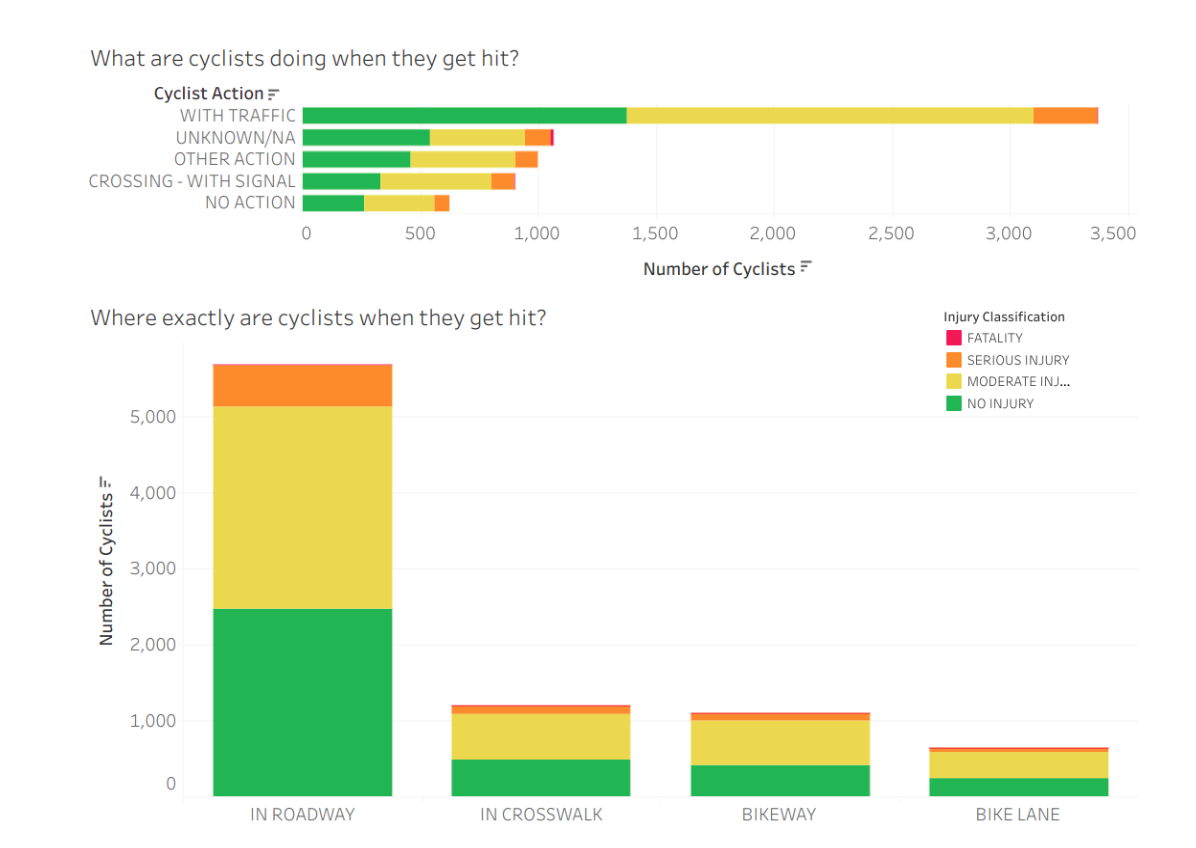

Similarly, the numbers don't suggest that most people struck while biking were doing anything illegal. For example, the vast majority of those crashes involved people biking in the direction of traffic.

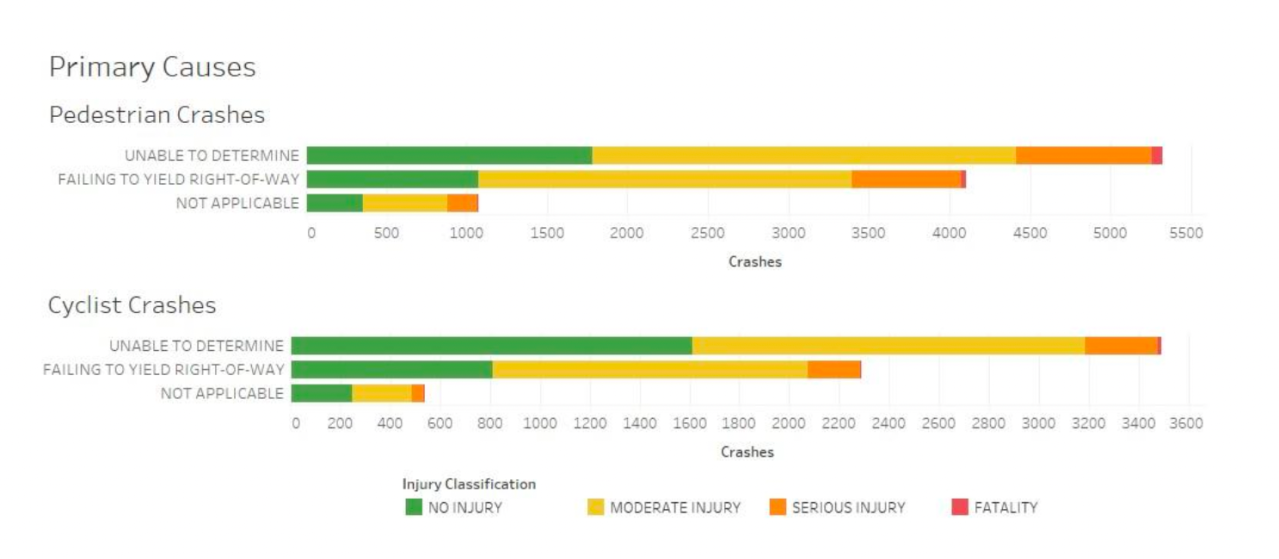

So it appears that people who get struck by drivers while walking and biking generally aren't tempting fate by behaving foolishly. So that means motorists are usually to blame for these collisions, right?

Yes and no. According to the data, Chicago traffic crash reports most commonly state that responding officers were "unable to determine" the primary cause for pedestrian and bike crashes. In layman’s terms, in most cases we simply don’t know why there was a crash. But in all traffic collision cases it's important to ask, “Did the street design and infrastructure allow or even encourage behavior that is known to lead to crashes?”

Let’s take speeding for example, since it’s a main factor in determining how likely it is that someone will be killed if struck by a driver. The dramatic decrease in traffic and significant increase in speeding, crashes, and fatalities during the pandemic suggests that our streets are designed in such a way that, in the absence of congestion, drivers will opt to travel at dangerous speeds.

It's clear that the layout of many Chicago roads doesn't force drivers to slow down at all. Stop signs and painted crosswalks are relatively ineffective because they are essentially optional. If you fail to make a complete stop or yield to pedestrians in a crosswalk and no police are present, there probably won't be any consequences for you, which is why this is such common driver behavior.

In contrast features like planted traffic circles, chokers (curb extensions that narrow a street), and raised crosswalks force drivers to slow down, or else risk damaging their vehicle or endangering themselves. The phenomenon at play here is called "risk homeostasis": We adjust our behavior to maintain a comfortable level of risk. That's why concrete (in both senses) infrastructure that makes motorists feel uncomfortable driving at unsafe speeds makes it safer to walk and bike. However, infrastructure such as "protected" bike lanes or temporary bump-outs created with paint and flimsy plastic posts are easy for drivers to ignore and even demolish with little risk to their own vehicles or safety, so they're much less effective at protecting vulnerable road users.

The second most common cause of crashes involving vulnerable road users is drivers failing to yield the right of way. There was a tragic example of this on September 8, when an elderly motorist failed to yield while making a left turn at Milwaukee Avenue and Huron Street in River West, fatally striking youth mentor Sam Bell, 44.

And, again, more than 7,000 of the pedestrians struck in Chicago since 2020 were hit in crosswalks. Why is it so common for drivers to ignore state law by failing to stop for people in crosswalks? Maybe it’s because many of them look like this:

While a driver who is paying attention here would notice the marked crosswalk and pedestrian crossing sign, which suggest that motorists should be on the lookout for people crossing the street, but they have no "teeth." There's nothing about the street layout or infrastructure that leverages risk homeostasis to force motorists to slow down, let alone stop, for pedestrians.

The same can be said of most bike infrastructure in our city. Violating painted bike lanes, or even lanes delineated by flexible posts, has little or no risk for a motorist or their vehicle, which is why it's so common for people to drive and park in them. On the other hand, if you try to drive across a concrete curb protecting a bike lane, or up onto a raised bikeway, you're definitely going to feel the impact, and possibly damage your car. Again, the most effective safety infrastructure makes drivers feel uncomfortable behaving in ways that would endanger other road users, because it would also put themselves at risk.

Fortunately, there are many, many traffic calming features that provide effective visual cues to drivers that they need to slow down or else risk harming themselves and/or their cars. These can and should be installed whenever roads are maintained or upgraded.

However, Chicago's dearth of robust traffic safety infrastructure has never been due to a lack of know-how. Rather, all too often city officials opt for relatively ineffective tactics like speed feedback signs or non-protected bike lanes because they are politically safe, since they do not inconvenience drivers. It's almost as if the Chicago Department of Transportation is more willing to risk having drivers run over some flimsy plastic posts and strike people riding in "protected" bike lanes, than to install rigid bollards that would protect human beings, but might dent a reckless motorist's fender.

Another problem is the lack of coordination and will among City Council members to prioritize the safety of people on foot and bike. For example, in 2019 Ald. Walter Burnett (27th) ordered the removal of a concrete median on Madison Street in the West Loop in order to make driving more convenient. If that infrastructure had been left in, it likely would have prevented an intoxicated driver from veering into oncoming traffic and killing bike rider Paresh Chhatrala, 42, on April 16 of this year.

44th Ward alderperson Tom Tunney was recently prepared to let CDOT resurface a stretch of Belmont Avenue in Lakeview without installing robust protected bike lanes that connect with the Lakefront Trail. That's despite the fact that drivers have struck 59 people walking or biking on that segment of Belmont since 2017. After some 180 people showed up for a bike protest to call attention to the issue earlier this month, Tunney announced that he was delaying the project for further discussion.

And let’s not forget the 18 alders who voted this summer for an ordinance that would have allowed motorists to speed by up to 9 mph near schools and parks. Unfortunately there are too many other examples of wrongheaded anti-bike/ped actions by alders to enumerate here.

Alders have an outsized influence on infrastructure in their ward, and can use this clout to make walking and biking safer or more dangerous. We must hold them accountable to use their power for good.

Another crucial but less obvious roadblock to safer street design is the Illinois Department of Transportation, which often blocks meaningful pedestrian and bike safety improvements to the Chicago roads they control if there's any risk that the changes might increase trip times for drivers. North Avenue in West Town, discussed above, is a good example. What it really needed from a recent redesign was a "road diet" with fewer lanes for drivers and concrete-protected bike lanes, but all that IDOT would allow was a five-lane highway with nearly useless painted bikeways.

"IDOT’s roadway design standards are one of the biggest hurdles to building safe streets," David Powe, director of planning and technical assistance at the Active Transportation Alliance, argued. "Right now, cities must design their roadways, intersections, and bike lanes to accommodate semis and delivery vans. Safe, human-centered roadway design will require statewide leadership to change the standards IDOT mandates for building transportation infrastructure across the state." When politicians and transportation officials aren't willing to ask drivers to give up some convenience in the form of fast travel times and super-easy parking in order to accommodate safer street designs, people are sacrificed instead.

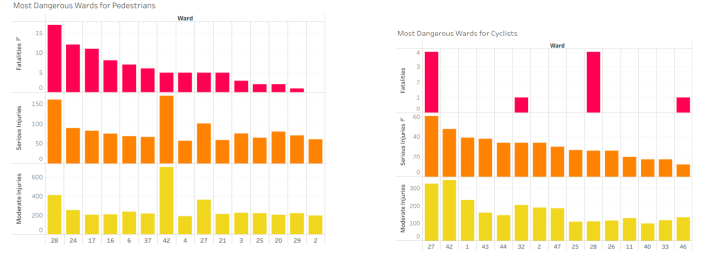

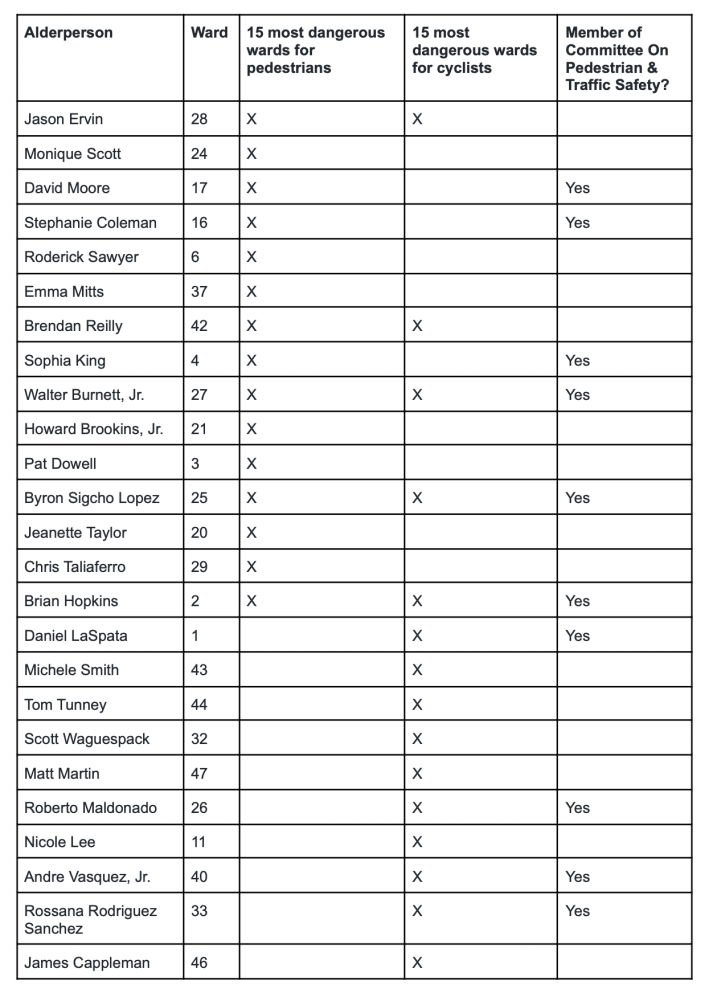

Obviously the entire city of Chicago should get robust walk/bike safety upgrades. But there are particularly problematic wards that should be prioritized for improvements. The charts above and below show the 15 most dangerous wards for people on foot and the 15 most dangerous districts for people biking, with the most pedestrian and bike injury and fatality crashes since 2015. While a particular alderperson may or may not have been in office during the past seven years, their constituents have been feeling the effects of living in traffic violence hotspots the entire time.

It is time for the City Council, state legislators, and the city and state transportation departments to implement a radical redesign of our streets. We need infrastructure that has safety, not danger, built into it. This will take political courage, and it might inconvenience some drivers, but it will definitely save lives.