Last month I rode Amtrak to New Orleans. On the evening we left, I planned to catch a #81 Lawrence bus with my suitcase west from my home in Uptown to meet my friend at the Ravenswood Metra station. We'd catch the Union Pacific North line downtown to the Ogilvie Center, and then roll our luggage three blocks to Union Station.

It was about 6 p.m. on a weekday, and buses should have been running frequently, but I waited more than a half hour for a westbound run, while several eastbound buses passed me by. Running out of time to catch our Metra train, I wasted $12 on a traffic-clogging and pollution-generating Lyft ride to the station.

Unlike Chicago, New Orleans doesn't have a reputation as one of the country's best transit cities. But after getting used to unpredictable CTA service gaps during the COVID-19 pandemic, and CTA Bus and Train Tracker arrival times that often have no basis in reality, we found NOLA's Regional Transit Authority to be refreshingly reliable. On the many occasions when we took streetcars and buses during our visit, the vehicles showed up almost exactly when Google Maps or the Transit App said they would.

In contrast, even as the pandemic has eased and COVID-related transit worker absenteeism has become less common, Chicagoans are still dealing with chaotic, unpredictable service that makes it difficult to get to work, school, and appointments on time without scheduling extra "slop" time, in case there's an unforeseen delay. For example, I used to tell people to allow 45 minutes to an hour to ride the Blue Line from the Loop to O'Hare. Nowadays I'd recommend allowing 1.5 hours to make sure you don't miss your plane.

It's low-income and working-class people who live on the South and West sides and in blue-collar suburbs, who are hurt the most by long service gaps and "ghost" runs that disappear from the tracker screens before they arrive. That's especially true of third-shift employees like security guards and janitorial workers. These are the folks who are least likely to have the time and resources to complain to the CTA, elected officials, or the media about bad service.

However, last January Streetsblog's Ruth Rosas spoke with Carlos, a Cicero resident who has worked in Chicago's Hermosa neighborhood for the last eight years. He said he's had to endure a significant increase in his commute time during the pandemic. He typically rides the #60 Blue Island/26th and #53 Pulaski buses to get to and from work. If he misses a bus, the wait for the #53 can be more than a half hour. Delays are particularly bad on weekday afternoons when schools are letting out when, “Sometimes it’s 30 minutes, sometimes it’s 45 minutes, and sometimes two to three buses show up together.”

One data analysis from earlier this year found that only about half of scheduled Blue Line runs were actually materializing.

The service gap problem isn't entirely the CTA's fault. Like most or all major U.S. transit systems, during the pandemic the CTA has been heavily impacted by staffing shortages due to COVID-related absences, high rates of retirement and difficulty recruiting new hires. It's been a time when bus and train operators have faced coronavirus transmission risks, and dealt with high levels of bad behavior, and even violence, from riders.

Now that the crisis has ebbed, it's still challenging to find new employees due to the continuing nationwide dearth of available workers. The CTA is trying to do a better job of recruiting and retaining operators, including last February's approval of a new contract with the transit workers union that included raises and retroactive hazard pay.

During the depths of the pandemic, when Chicago transit ridership plummeted due to Stay at Home, Mayor Lori Lightfoot often boasted that Chicago was the only major U.S. city that didn’t cut transit service. But that was only true on paper.

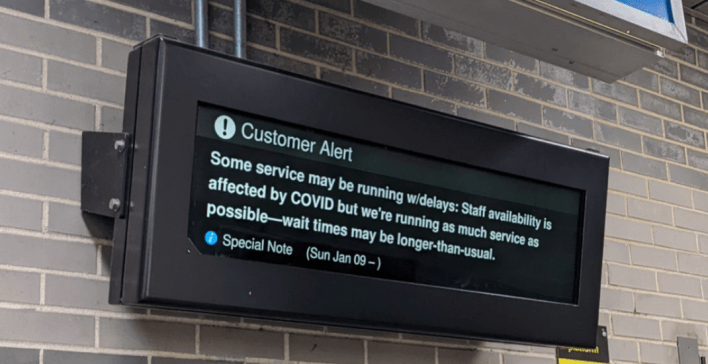

However, earlier this year the CTA started running announcements that came closer to acknowledging reality. They basically said, "We haven’t cut any scheduled runs, but unfortunately we don’t have enough operators to staff all our buses and trains, so occasionally there are service gaps – please bear with us.”

But it's clear this approach to dealing with the labor shortage – where there's no way to predict whether a scheduled bus or train is actually going to show up – is no longer acceptable to Chicagoans. The untrustworthy Bus and Train Tracker arrival times add insult to injury.

Yesterday Ald. Carlos Ramirez-Rosa (35th) introduced a City Council resolution, signed by 33 other alders, calling on the CTA to present a plan for addressing the service gap and reliability problem. “Chicago residents have reported less Chicago Transit Authority train and bus service, inconsistent train schedules, and regular delays that often leave them stranded [at a bus stop] or platform for thirty-plus minutes at a time,” the document notes.

Now I'd like to stage my own intervention for the CTA. It's a "Come to Jesus" moment for the agency, if you will.

It's time for the agency to take a pragmatic approach to its labor challenges, and be realistic and transparent about how just much service it can actually provide. That's a much healthier approach than propping up Mayor Lightfoot's emperor-has-no-clothes-style fable that the system is still operating at full strength.

How about all of us on the Clark/Division platform who had to wait for 3 trains to go by that looked like this? pic.twitter.com/6oSIne5CqD

— Kelly Johnson (@kellysonofjohn) June 24, 2022

In addition, those non-fictional bus and train runs should be reallocated to the times and places where they're most needed.

For example, far fewer office workers are currently commuting downtown at the moment than during pre-pandemic times. So would it make sense to cut some daytime weekday runs on the Brown, Purple, and Yellow lines, which largely serve predominantly white-collar neighborhoods and suburbs?

Meanwhile, many essential workers never stopped commuting from South and West Side communities. It might be prudent to add more service to train and bus routes that have continued to have relatively high ridership. For instance, the #79 79th Street bus actually experienced crowding issues during lockdown.

I've been told that a dearth of part-time CTA bus drivers who operate special runs, called "trippers," is an especially vexing problem. For example, extra runs are scheduled after public schools let out, so that hundreds of students aren't stuck waiting outside for a ride. But nowadays these additional buses often fail to show up. Reallocating service to cover these trips is crucial.

And since people currently report service gaps during weekend special events that draw lots of transit riders, it's just common sense to make sure all runs are staffed on the relevant routes. "Gas is crazy expensive and we have the existing infrastructure to get people downtown!" noted writer Leigh Giangreco on Twitter. "People will use the L again if it runs on time!"

But the most important thing is, the CTA needs to stop lying to its customers by saying it's providing service that doesn't really exist. While the agency has admitted to staffing problems, it hasn't actually adjusted its timetables so riders can have realistic expectations.

The truth hurts, but the CTA must bite the bullet and publish lighter, reality-based schedules. Basing the Transit Trackers on these, rather than wishful thinking, would basically make ghost runs a non-issue.

I sent a rough outline of this op-ed to the CTA before writing it. Spokesperson Brian Steele said my general assessment of the current service gap situation was accurate. "The only thing I’d add is that since the start of the pandemic, CTA has made a number of changes to reallocate service hours to match where demand is. For example, at the start of the pandemic, on some routes and rail lines, we cut back on AM peak service (as there were fewer commuters) and added service in the midday and PM."

"Now that traditional AM and PM peak commuters are coming back, we’ll begin to increase AM service to meet that demand," Steele added. "Another example is the addition of articulated buses on routes like the #66 Chicago and #79 79th Street to meet higher demand on those routes."

So wait, I responded to Steele, you just said that the CTA "cut back on service" on some routes and lines. How does that jibe with the mayor’s assertion that, unlike other major cities, there were no service cuts?

"We have always said that we didn’t cut scheduled service," Steele replied. The word "scheduled" is doing the heavy lifting in that sentence.

The bottom line: The CTA needs to do the honest and responsible thing. It must change its published timetables so that "scheduled service" and actual bus and train runs begin to at least remotely resemble each other.