Yesterday the Metropolitan Planning Council held a virtual discussion of transit fare integration. “Rethinking Regional Transit: Power and Potential of Fare Integration” brought together panelists with experience working on fare integration. MPC’s director of transportation, Audrey Wennink moderated the event. The panelists were William Bacon, principal for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission of the San Francisco Bay Area (analogous to Chicagoland's Regional Transportation Authority); Illinois state rep and transportation advocate Eva-Dina Delgado (3rd); Kevin Desmond, principal and national director of transit and rail for Sam Schwartz Engineering; and Molly Poppe, chief innovation officer at the CTA.

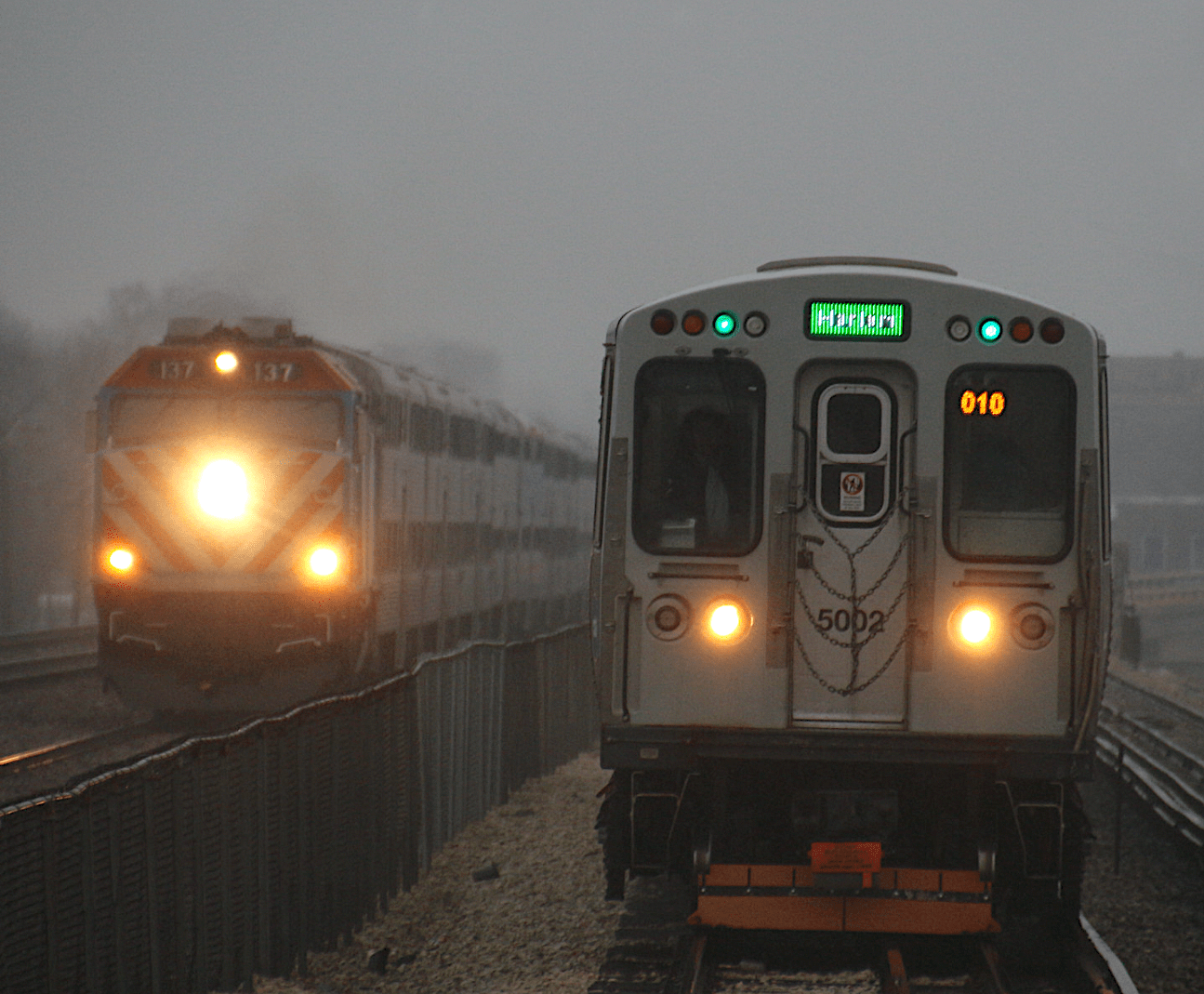

In an ideal world, a universal fare card would allow a person to make transit trips that involve seamlessly moving between two or three different systems. In some ways that was the promise of Ventra when it was launched in 2013: the ability to use the CTA, Pace, and Metra via the same card. Some transit advocates would like to go a step further and have one fare for one transit trip, no matter how many systems you use. One of the sticking points is, who exactly would get the fare: the first system you ride, the second one, or perhaps the third? Should the fare be split between the different systems?

Desmond was asked to give his experience working on fare integration and to share any insights learned and benefits he’s seen. He shared that fare policy and fare integration has been a part of his professional experience for years. He worked with the New York MTA when it rolled out the electronic Metrocard in the 1990s. Most of Desmond’s shared insights pertained to his work as a senior executive at a small transit agency in the Pacific Northwest and as general manager at King County Metro, which serves the Seattle region. He pointed to the development of the King County ORCA card (One Regional Card for All), which is accepted by six local transit systems.

Desmond highlighted three preconditions for successful regional fare integration: shared vision among the transit agencies, most importantly an understanding of the mutual interests within fare integration; clear institutional policy directives; and good faith interagency collaboration. The key catalyst for the fare integration aspect of the ORCA card was the creation of their regional transit authority via a ballot initiative. An explicit obligation mentioned in the ballot measure was to facilitate regional fare integration. Funding was provided to get fare integration off the ground. It was later found that higher ridership offset the cost of fare integration, making it a revenue-neutral initiative. Higher customer satisfaction was another perk of fare integration.

Before COVID Sound Transit, which operates light rail, commuter rail, and express bus service, was leading the United States in ridership growth. Desmond noted that service expansion, population growth, and high traffic congestion were driving factors in increased ridership. Desmond also believes that the convenience of fare integration as users moved from one transit system to another was also key to ridership growth. The creation of the ORCA card helped to enable the creation of the ORCA Lift program, reduced fare transit pass for low-income adults, a few years later.

Next William Bacon of San Francisco shared some of the challenges he’s facing in his work on fare integration for Bay Area transit operators. He said the Bay Area has very fragmented transit service. There are at least 27 transit operators, and arguably more than that. Each agency is independent and has its own governing boards. California’s transit funding structure incentivizes locally focused transit fares. There are often a variety of voter-approved sales taxes or property tax measures to fund services within a particular area. Over time this has led to an “increasingly bewildering array of fares that exist between agencies.”

Agencies may have their own negotiated transfer discounts between connecting services, but not necessarily with all the systems they interact with. “It’s very challenging for users to know what fare they are likely to pay," Bacon said. "Sometimes it even depends on what direction you’re going. Policies vary from agency to agency.” He noted that the Bay area is fortunate to have the Clipper card, a smart-card system that covers each agency. However, Bacon said the policy component is lacking. “How do we incentivize riders to take trips that involve multiple transit agencies? Despite significant investment and population growth, transit ridership per capita has stalled or even declined for some agencies. This has spurred brainstorming around looking at operations and equity.”

In terms of equity, the California housing crisis is a major issue, Bacon said. Due to high housing prices, employees often have to live far from their workplaces. The most vulnerable transit riders are facing the highest fares because they take the longest journeys to access jobs, education, healthcare, and child care. There is a serious concern about who is paying the most for transit.

According to Bacon, these concerns have led some transit agencies to ask, “Does that [cost burdens for vulnerable riders] match our priorities and values?” There’s also a shared desire among transit agencies to deliver the best product/experience they can. Bacon stated that his working group is on track to deliver free transfers between transit systems and a regional pass. Neither of these things have existed before. “A shared sense of purpose and fostering trust between agencies has been instrumental.”

Molly Poppe from the CTA was asked what new improvements could be coming to Ventra. Poppe began by looking back at the initial rocky 2013 rollout of Ventra. “It was a massive transition for the CTA!” Since that time, the agency has worked to ensure that Ventra is a stable platform for users, she said. Transit riders can pay for Pace, Metra, and CTA trips through the Ventra app, as well as rent Divvy Bikes. Google Pay and Apple Pay were added to facilitate easier fare payment. The next Ventra update will allow for 3rd-party integrations from a technical and fare standpoint. As more transit agencies migrate to Ventra for fare payment, it will be possible to use Ventra for several transit agencies across the country.

On the Chicagoland level, state rep Eva-Dina Delgado is working on HB4608, a bill would “amend the Regional Transportation Authority Act to direct the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and its [Metropolitan Planning Organization] Policy Committee, in coordination with RTA, to develop and submit a report of legislative recommendations to the governor and general assembly regarding changes to the recovery ratio, sales tax formula and distributions, governance structures, regional fair systems, and any other changes to state statute, authority, or service board enabling legislation, policy, rules, or funding that will ensure the long-term financial viability of a comprehensive and coordinated regional public transportation system that moves people safely, securely, cleanly, and efficiently and supports and fosters efficient land use.” The bill instructs the organizations to comply with this amendment by January 1, 2023 with the intention of the amendment being repealed a year later due to a successful and actionable report.

Delgado asked her social media followers what would get them on transit. She said most the responses pertained to fares, with many people asking for lower fares. Poppe from CTA responded that the agency heard its customers feedback around fare affordability and recently used some of the federal COVID funding it received to lower the cost of passes and eliminate the 25-cent transfer fee in its 2022 budget. As a result of the fare reduction, she said, there's been a significant increase in pass use, especially among bus riders.

I hope we see seamless fare integration for CTA, Pace, and Metra, along with am ORCA Lift-style discounted pass for low-income riders by the middle of this decade, if not sooner.