Traffic safety and sustainable transportation advocates have long promoted automated enforcement cameras as an effective way to reduce injury and fatality crashes caused by speeding and red-light running, without the potential for racial profiling and violence that exists when police officers conduct traffic stops.

However, for years transportation advocates of color have pointed out that there's still a possibility of racial and economic inequities in the way traffic cameras are deployed. For example, In 2017 Oboi Reed, currently head of the Chicago-based mobility justice nonprofit Equiticity, discussed the pros and cons of automated enforcement during an online discussion of the Vision Zero crash elimination movement. While Reed strongly advocated against using additional traffic policing as part of Chicago's Vision Zero program, which launched that year, he acknowledged the potential for speed and red light cameras to help eliminate racial bias from enforcement.

But Reed added that the cameras shouldn’t be concentrated in communities of color, which – due in part to racist 20th Century urban planning – are more likely to have car-centric street layouts that encourage speeding, as well as higher levels of serious and fatal crashes. Moreover, he said, the penalties shouldn't be regressive, disproportionately impacting low-income residents.

A year earlier I'd argued in a Chicago Reader op-ed that traffic fines should be income-based, as was already the case in several European countries, and diversion programs like traffic school should be offered as an alternative to fines.

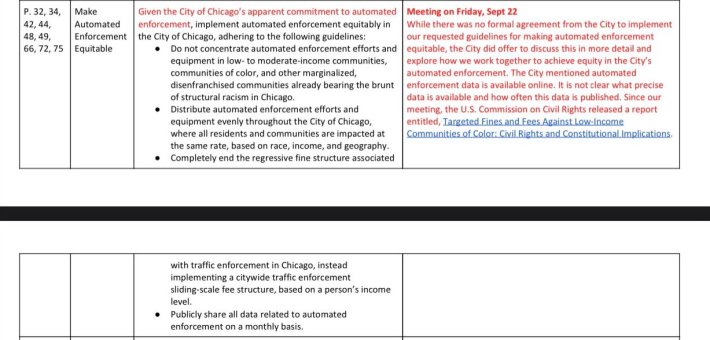

Reed recently revealed that in 2017 he and other Black transportation advocates made recommendations to Chicago officials on ways to make the city's automated enforcement program, originally launched in 2003, more equitable. These included not putting a disproportionate number of cameras in Black and Latino communities; ensuring the camera placements impact all residents and communities equally in terms of race, income, and geography; implementing an income-based fine system; and publicly sharing automated enforcement data. While most of these recommendations are currently in place or launching soon (more on that in a bit), Reed said the city did not formally agree to them at the time.

First the good news about Chicago's automated enforcement program: Multiple studies have found that the cameras are doing their job by preventing a significant number of traffic injuries and fatalities.

A city-commissioned report on the red light camera program conducted by Northwestern University researchers released in March 2017 concluded that they resulted in an overall ten percent drop in injury crashes, with a 19 percent reduction in particularly dangerous “T-bone” and/or turning collisions. The study also noted a “spillover effect,” with the cameras resulting in less red light running at intersections that don’t have the cams.

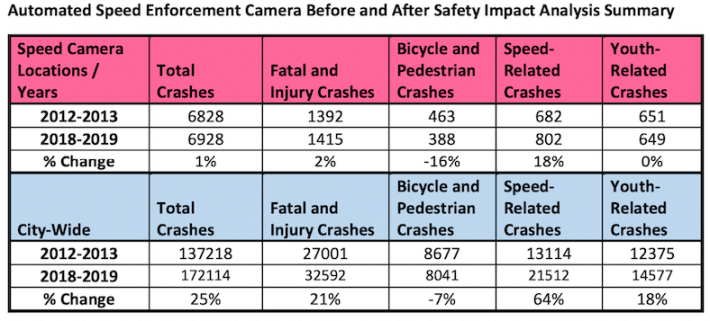

A recent Chicago Department of Transportation analysis of the speed cameras compared of crash data from 2012-13 (before CDOT installed the cameras) and 2018-19. The department found that while serious injury and fatal crashes increased by 21 percent citywide during this six-year period, the increase was only 2 percent within the eighth-mile zones around the cameras. And while speed-related crashes spiked by 64 percent citywide during this period, they only went up by 18 percent in camera zones.

Still more evidence that automated enforcement is saving lives was last Tuesday's release of the executive summary of a study the city commissioned from University of Illinois at Chicago researchers. (To my knowledge, the full report has not been released yet.) They concluded that during the period of 2015 to 2017, compared to expected traffic violence levels, the speed cameras reduced the number of severe and fatal injuries by 15 percent, and prevented 204 people from being injured (at any level of severity) or killed.

The UIC report, titled "Red-Light and Speed Cameras: Analyzing the Equity and Efficacy of Chicago’s Automated Camera Enforcement Program," was written by Dr. Stacey Sutton and Dr. Nebiyou Tilahoun, professors in the university’s Department of Urban Planning and Policy. Due to the prior Northwestern study, the city didn't ask them to look at the effectiveness of red light cameras.

So there's no question that Chicago's automated enforcement program is effective in delivering safety benefits. However, the UIC study also found racial and ethnic disparities in who the cameras recorded breaking traffic laws. Drivers of cars registered to households in majority-Black census tracts were most frequently caught speeding or running reds, followed by majority-Latino tracts, compared to majority-non-Hispanic white (henceforth referred to as "white") and majority-Asian-American tracts.

(Tickets are issued to the car owner, who is not always the person who committed the violation. And some people who commit infractions may live in a neighborhood with completely different racial or ethnic demographics than the owner. However, that percentage is likely so small that I will proceed by simply saying "drivers from majority-X census tracts or ZIP codes," rather than continuing to use the clunky phrase "drivers of cars registered to households in majority-X census tracts or ZIP codes.)

One could argue speeding and red light tickets are totally optional, and there's nothing inherently inequitable about the program if it happens to be the case that Black and Brown Chicagoans choose to speed or blow stoplights at higher rates than other residents. After Streetsblog Chicago reported on the UIC findings, many of our readers took an "If you can't do the time, don't do the crime" attitude.

Though person taking a sample did not record trail users crossing there, we DO exist. More people use the trail each year Being *able* to cross 127th St factors into that increase. 2/

— AKA60643 💜🩷❤️🧡💛💚💙 (@aka60643) January 12, 2022

More importantly, though, Hopkins and Sanchez highlighted the key issues that the built environment and housing density play a huge role in whether drivers are encouraged to speed. They provided these thought-provoking statistics:

ProPublica found that all 10 locations with the speed cameras that issued the most tickets for going 11 mph or more over the limit from 2015 through 2019 are on four-lane roads. Six of those locations are in majority Black census tracts.

Meanwhile, eight of the 10 locations where the fewest tickets were issued are on two-lane streets. And just two of the 10 are in majority Black census tracts. (The analysis focused on cameras near parks, because those devices operate for more hours and days than those by schools, leading them to issue the vast majority of tickets.)

However, the authors clarified to me that they didn't actually determine that speed cameras in majority-Black census tracts are more likely to be located on four-lane roads than in other kinds of census tracts, or that speed cams installed in majority-Black census tracts are less likely to be on two-lane roads than in other communities. Therefore, the disparity they identified, that most of the highest-ticketing cameras are located on four-lane roads in African-American neighborhoods, and vice-versa, is not necessarily an inequity.

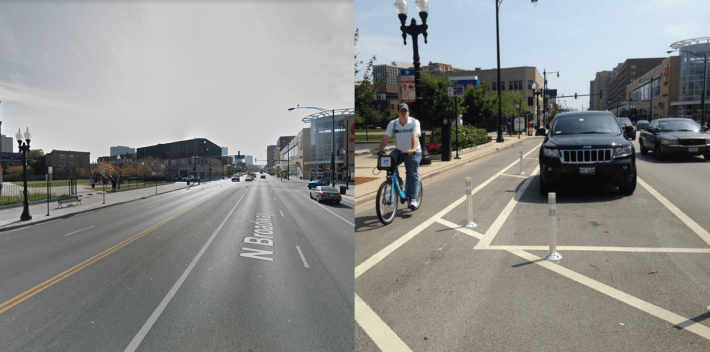

But if it's actually true that speed cameras in African-American communities are more likely to be on four-lane roads, as well as the opposite, that would clearly be unfair. Therefore, CDOT needs to study that issue and make changes to camera locations if needed.

Ideally the department would also implement "road diets" on all four-lane streets with speeding problems. This strategy involves reducing the number of mixed-traffic lanes on a street and using the extra right-of-way for sustainable transportation facilities like wider sidewalks, protected bike lanes, and bus lanes. It's especially appropriate for a street like 127th that is missing a sidewalk.

Whether or not further analysis reveals major camera placement equity issues, the ProPublica piece does a good job of laying out the massive financial toll that camera-recorded speeding and red light violations have taken on the finances of Chicagoans of color. "The consequences have been especially punishing in Black neighborhoods, which have been hit with more than half a billion dollars in penalties over the last 15 years, contributing to thousands of vehicle impoundments, driver’s license suspensions and bankruptcies."

At the end of Hopkins' and Sanchez's article, UIC researcher Stacey Sutton is quoted comparing the downsides of Chicago's traffic camera program to inequities associated with in-person policing. “It’s the same cycle, right, in terms of [Black and Latino residents'] interaction with the state and with the justice system. But the way you enter that is not through a police officer, but through this supposedly unbiased technology... I don’t think there’s a technological fix to an unjust system.”

One might interpret that statement as arguing that automated enforcement is fundamentally unfair. That made me wonder why Sutton bothered to create a list of ideas to improve the Chicago program, if she thinks that's a lost cause.

But Sutton told me that's not what she meant. "I think our recommendations are sound. Assuming the city were to adopt all of them, I believe the camera system would be more equitable... [But] poor people have always been thrust into the justice system because of poverty. So the 'unjust system' I refer to is a structural problem that cannot be remedied through a technological change or isolated policy."

Active Transportation Alliance spokesperson Kyle Whitehead said the UIC and ProPublica reports "shows much more reform is needed to maximize the safety benefits of cameras and minimize the harm to vulnerable Black and Brown communities." However, like Sutton, he expressed the belief that Chicago's program can be made more fair. "This research and the mayor’s recent fine reforms are steps in the right direction. Now the city must adopt the [UIC] report’s recommendations and continue to be more transparent about camera locations, regularly analyzing the safety impacts and moving or removing cameras as needed."

But Oboi Reed told me that while back in 2017 he was agnostic about automated enforcement, these recent findings have convinced him that Chicago's traffic camera program is fundamentally broken and needs to be dismantled. He said he was particularly troubled by the revelation in the ProPublica piece that while in 2020 the UIC professors shared with city officials their initial findings that Black drivers were racking up more tickets, and the city then hired the researchers to further study the issue, Mayor Lightfoot still lowered the speed camera ticketing threshold from 10 mph to 6 later that year.

The mayor pointed to a 39 percent spike in on-street Chicago traffic deaths during the first nine months of 2020, likely due to more speeding as a result of lower traffic volumes during Stay at Home, as her motivation for the change. I didn't endorse lowering the threshold during the depths of the pandemic, a time of economic hardship.

The graph below from CBS Chicago shows that after Chicago speed cameras began issuing ticketed for 6 mph+ violations on March 1, 2021, the number of citations skyrocketed compared to previous years. However, from the peak in ticketing on May 1, through November, the number of recorded speed violations steadily fell to nearly the same level as previous years, which suggests the new rule has been very effective in encouraging safer speeds.

!function(){"use strict";window.addEventListener("message",(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data["datawrapper-height"]){var t=document.querySelectorAll("iframe");for(var a in e.data["datawrapper-height"])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data["datawrapper-height"][a]+"px"}}}))}();

"Equiticity's position is automated enforcement is not the right solution," Reed told me. "Our primary position is that the most effective way to reduce traffic violence is not punitive measures, but safety infrastructure." He pointed to traffic calming strategies like road diets, and installing speed humps, pedestrian islands, sidewalk bump-outs, and other tactics that discourage speeding and make walking and biking safer. CDOT installed 400 such "Complete Streets" projects last year, with a focus on high-crash areas on the South and West sides identified in the Vision Zero plan, and 400 more projects are slated for 2022.

Data from other cities suggest that if Chicago's traffic camera program were to be abruptly shut down, many more residents would be injured and die in crashes. A 2017 study by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety looked at 19 cities that removed red light cams during the previous decade. Compared to peer cities that kept their cams, the rate of deadly crashes at intersections with stoplights was 16 percent higher in the cities that removed them. And after Houston banned RLCs in 2010, fatal intersection crashes increased by 30 percent, and collisions rose 116 percent overall, according to data from Houston police.

Moreover, the Vision Zero Chicago Action Plan findings indicate that if our city's automated enforcement program was immediately cancelled, a greatly disproportionately number of Black residents would be injured and killed as a result.

As such, Reed said he would support gradually replacing traffic cameras with similarly effective traffic-calming installations, earmarking revenue from the cams to pay for the infrastructure.

That seems like a reasonable approach to me, but it's a solution that's much easier said than done. A major obstacle to that strategy is that many of the people who loudly protest that automated enforcement is unfair to motorists are the same folks who bitterly oppose road diets, or any other street changes that make driving a little less convenient.

It's either tickets or safe streets. I would frame it in that way. I'm also just sick of asking people if we can design streets that lead to fewer serious injuries and deaths. F--- public approval when it comes to safety.

— Courtney Cobbs (they/she) (@FullLaneFemme) January 13, 2022

For example, South Side alderman Leslie Hairston has been a vocal opponent of speed cameras and red light cameras. But in 2016 she helped kill a CDOT proposal for a road diet with protected bike lanes on eight-lane Stony Island Avenue in her ward, arguing that reducing the number of lanes for drivers to a mere six lanes would cause traffic jams.

Two years after Hairston blocked the project, a driver fatally struck Luster Jackson, 58, while he was riding a bike on that stretch of Stony Island.

And the following year a motorist struck and killed Lee Luellen, 40, while he was biking on Stony Island, only five blocks north of where Jackson was killed. That driver was cited for failure to reduce speed.

But Reed told me he doesn't think opposition from car-focused aldermen and residents should be a major obstacle to replacing automated enforcement cameras with effective traffic calming. "The mayor lowered the ticketing threshold to 6 mph in the face of significant opposition. Why can't she overhaul Stony Island in the face of opposition too?"