Para leer este artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

I was born and spent my early childhood in Mexico, so I grew up speaking Spanish. But after my family immigrated to the U.S., I lived in a predominantly English-speaking rural town in Northern Illinois. As I learned English in school, I had to translate for my family. The demographics of this country have changed since then. Nowadays the U.S. has the second-largest population of Spanish speakers, including native and bilingual Spanish speakers, in the world, after Mexico. Around 13 percent of the U.S. population speaks Spanish at home, which means Spanish is the second-most common language.

In the Nineties, the population of Spanish speakers in the U.S. doubled, and it continues to grow to this day. We have seen major changes to language accessibility, such as bilingual services and translated information and materials. It is rare to call customer service without a Spanish option being available. Bilingual services are offered in many venues and stores. Schools offer dual language programs. Yet, there is so much more progress to be made, especially when it comes to many government services.

While I just started writing and translating articles for Streetsblog Chicago, I am learning that language accessibility is very time consuming. I have already spent a considerable amount of effort searching for specific urban planning terminology in Spanish. My first go-to for information in Spanish is the city of Chicago’s official website, chicago.gov. Over 15 percent of Chicago residents don’t speak English. In 2015, the City Council passed the Language Access Ordinance, which ensures that “people can access critical services in the most common languages spoken in the city,” which are, in order of the number of speakers:

- Spanish

- Mandarin

- Polish

- Arabic

- Hindi

- Urdu

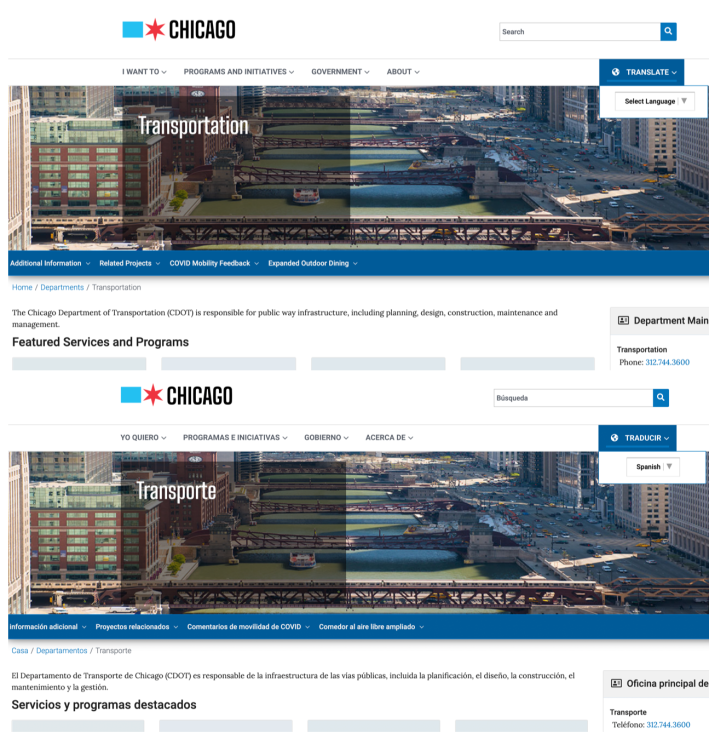

When you navigate the city's website, there is a visible Google Translate button that allows you to translate every internal chicago.gov webpages into most of these languages. (Translation to Urdu, a language commonly spoken in South Asia, is unavailable.) The translations provided by Google for Spanish are generally adequate. However, since these are computer-generated direct translations that don't account for all the nuances of the languages, sometimes the text can appear jumbled, and the sentences may be unintelligible.

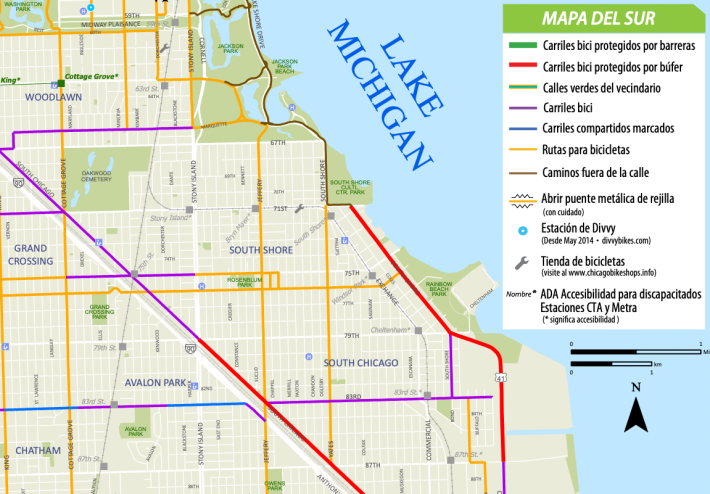

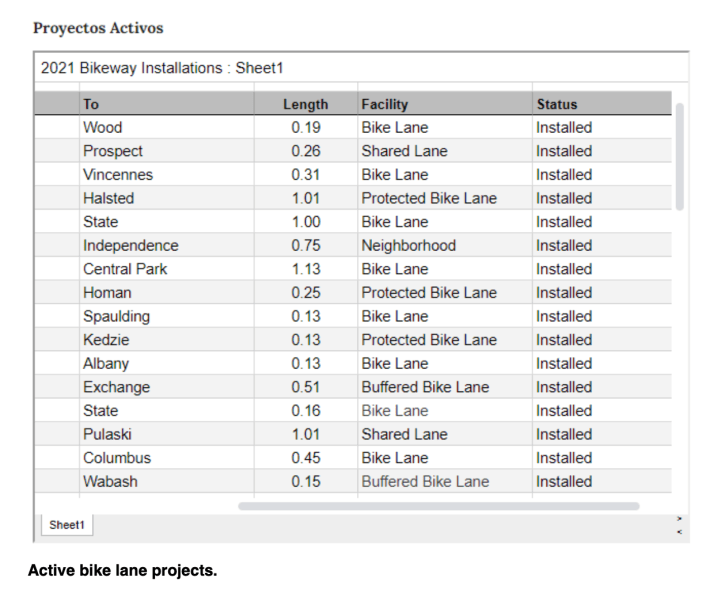

Navigating the Chicago Department of Transportation page in Spanish is relatively easy. CDOT has a lot of material for Spanish speakers, but most of the internal documents or external links are in English only. For example, a web page that provides an overview of CDOT's Strategic Plan for Transportation can be translated into Spanish, but the document itself is only available in English. While a Spanish version of CDOT's Chicago Bike Map was created in 2014, it hasn't been updated since then, so all the bike facilities installed over the past seven years don't appear on it. Every other CDOT document or infographic I've come across on the department's website were only in English.

As I translate my articles into Spanish, I realize there are terms in English that I have never heard in Spanish. Relatively new, technical terms, like, sidewalk bulb-outs are difficult to translate. CDOT-specific terms like Neighborhood Greenways are also difficult to translate efficiently. Looking for Spanish materials from other agencies, I run into the same problem. Some websites use the Google Translate function or are professionally translated, other pages like the ones for the Illinois and U.S. transportation departments lack translation services altogether. To find the appropriate translation for some terms, I must search for websites, articles, documents, and webinars from Latin-American countries or urbanist bloggers who write in Spanish.

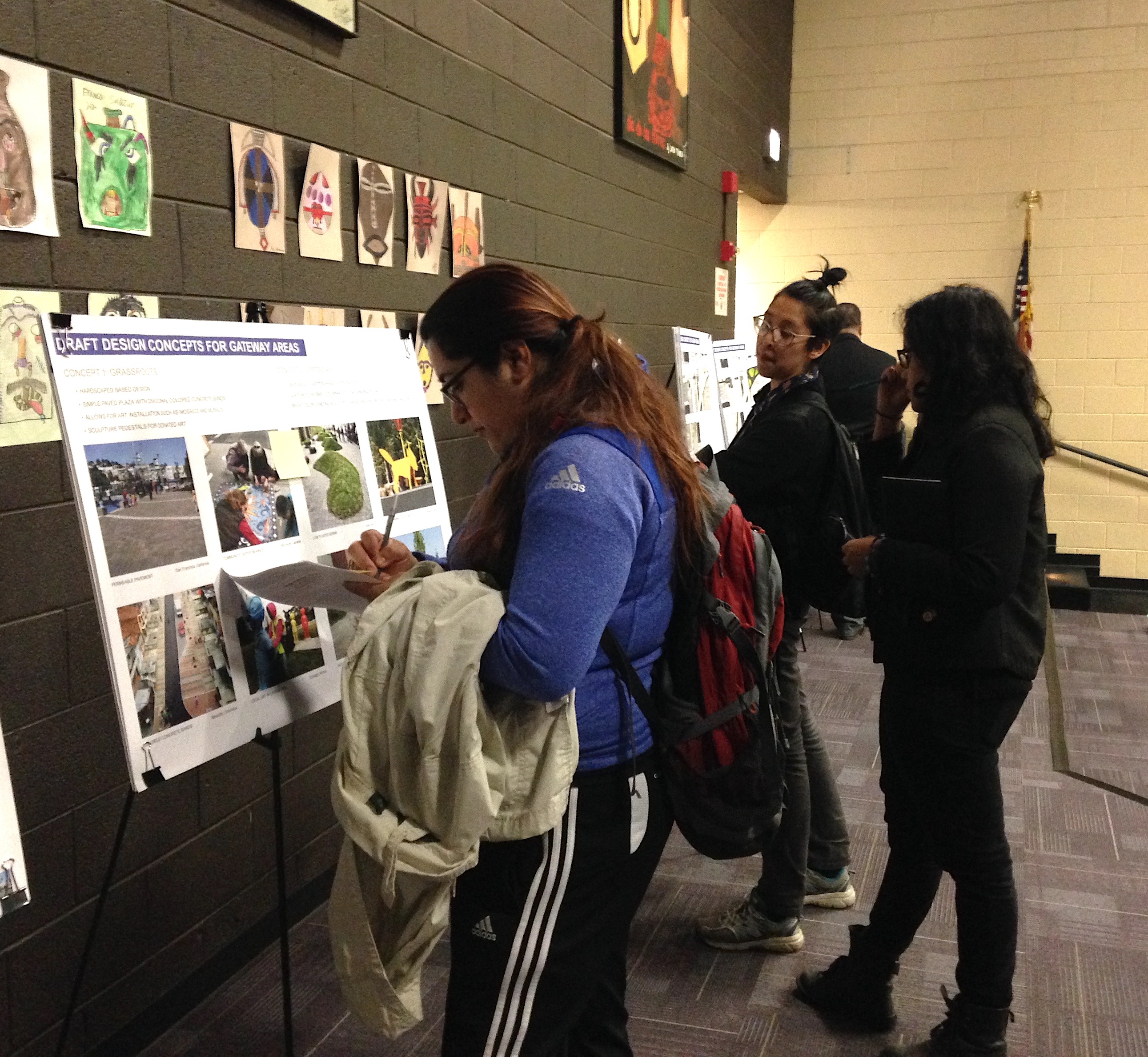

It has become customary for CDOT to provide Spanish translation in Spanish-speaking neighborhood meetings. As I listen to CDOT’s public meetings in Spanish, it is obvious that the difficulty of translating urban planning terminology extends beyond providing information and resources in Spanish. The content presented is inaccessible even to English speakers. Often, CDOT planners and engineers use unfamiliar words and phrases such as curb bump-out, chicane, refuge island, road diet, and so on. Semi-ambiguous or unclear words like livable, improvement, equitable are thrown in. Sometimes the presenter defines these words or imagery is used to illustrate the term, but even as someone who is well-versed in urban planning technical language, presentations can be confusing to follow.

These words and concepts may be understood by some people, but it isn’t enough to provide full community participation. The translation service can feel superficial, as if it is done only to check off a box, without much regard for whether Spanish-speaking attendees can engage with the concepts that are being discussed.

It makes me wonder if and how CDOT measures effective community engagement with Spanish speakers and others who may not be totally comfortable with English (or whether community engagement is measured at all.) There are also other elements to think about beyond translation. Replacing English text with text in another language is not enough to actually gather accurate feedback to informs planning decisions. We have to change much more than words to truly engage with and listen to input from non-English speaking communities.

Planners, engineers, and decision makers should recognize that the type of community engagement that allows residents to effectively collaborate may take more time and effort, and it may vary from community to community. The planning process also needs to consider social, cultural, racial, and class barriers to participation. This includes holding meetings on the weekends, providing opportunities to engage with other community residents, and compensating residents for their knowledge and assessments. This work requires planners and engineers to develop relationships and build trust, as well as transparency and accountability, cultural competency, and coalition building. Effective cultural competency means having more Black and Brown planners and engineers at the table and as decision makers. Coalition building helps dismantle race and class barriers to mobility.

We need more community education and conversations in plain language with localized context that the public-at-large can understand and engage with. In a field like planning, that is technical and political, and requires community participation, language accessibility is one necessary tool, but it does not guarantee that the voices of the community will have an impact.