If the proposed West Loop Metra station is built, it would be located along Hubbard Street between Ashland and Ogden avenues, potentially serving as a stop for all four Metra lines that currently run through the neighborhood: the Union Pacific West, Milwaukee District West, Milwaukee District North and North Central Service lines. But if it does happen, the station wouldn’t open until 2032 at the earliest.

On Tuesday, Ald. Walter Burnett (27th), the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, the Chicago Department of Transportation, and Metra held a virtual meeting to share the results of the feasibility study on constructing the station. The report looked at several potential station locations, and Ashland Avenue site came out ahead because of the proximity to the Ashland Green and Pink line station, the ability to serve two major transit and job corridors, and the fact that a station at that location could serve all four Metra lines.

But, as the officials reiterated several times during the meeting, the entire project hinges on the long-discussed A-2 interlocking project, which would build a flyover to allow the Milwaukee District/North Central tracks to pass over the Union Pacific West tracks. Until the flyover is built, it won't be possible to create a new station. Both projects would require federal funding, with the study estimating that the flyover would cost around $1.2 billion, and the station would cost another $400-500 million.

In the Near West Side community area the Union Pacific West Line runs on the embankment, but the tracks used by the other three Metra lines and Amtrak trains run at grade before joining the embankment west of Racine Avenue. But the biggest infrastructure issue is that the trains then need to cross the Union Pacific West tracks west of Leavitt Street in order to continue north. The crossing, known as the A-2 interlocking, also gets tied up when trains try to enter and exit the Western Avenue rail yard, and the fact that Union Pacific West tends to carry a large number of freight trains doesn’t help.

David Kralik, head of Metra’s long-term planning department, said that about half of all Metra trains have to pass through the interlocking. “It's bit like having a 4-way stop sign in the middle of the expressway,” he said.

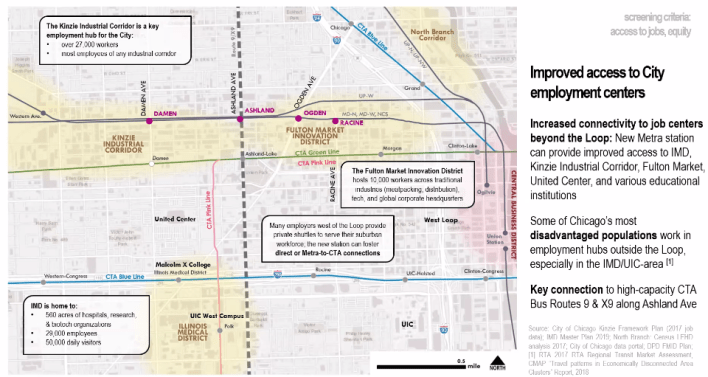

Kralik added that building a flyover would allow Metra to increase service to O’Hare International Airport along the North Central Service line, and beef up service on the two Milwaukee District lines. Jeff Sriver, head of transportation planning at CDOT, noted that the district lines provide the only rail service in several neighborhoods. The Milwaukee District West line serves Montclare, Galewood, Hanson Park, Hermosa and North Austin, while Milwaukee District West serves Hermosa, Old Irving Park, Mayfair, Forest Glen and Edgebrook.

The Western Avenue station directly east of the Western rail yard already serves the Milwaukee District and North Central lines, and the Union Pacific West line has a largely rush hour-orientated station near the other side of the rail yard at Kedzie Avenue, but there is currently no way to transfer between Union Pacific West Line and the other three lines without taking the train to the Loop.

As the Fulton Market area, previously known for manufacturing, warehouses, and food processing, has gentrified and gained several corporate headquarters, there has been a push to put in a Metra station in the neighborhood to better connect suburbanites to workplaces.

Kralik said CDOT approached Metra about the possibility of a new station while the department was studying the A-2 interlocking revamp. Sriver said that the goal isn’t just to bring suburban commuters to the West Loop, but also to provide connections for West Loop reverse-commuters to areas such as the office/retail areas in Schaumburg (which is served, albeit indirectly, by the Milwaukee District West line) and the Lake Cook Road corridor (which is served by the Milwaukee District North and North Central Service lines.)

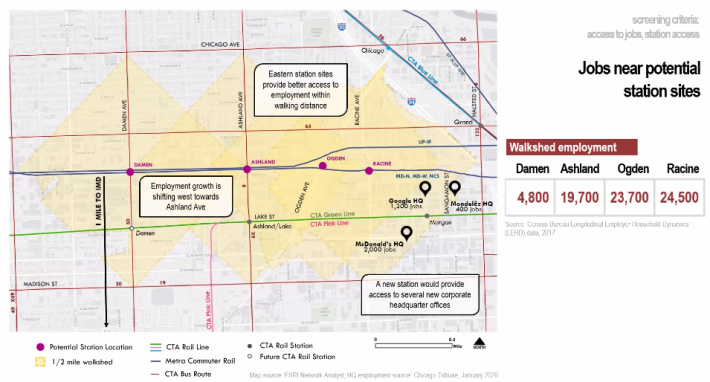

Sriver said the feasibility study considered five locations: Damen, Ogden, and Racine avenues, and Ashland Avenue either west or east of the street. While Racine would be closest to the major West Loop companies, they ruled it out because the station would have to be at grade. The study estimated that, during the morning rush hour, crossing gates are currently down a total of 30 minutes, or about one-fourth of the time. It projected that adding trains would mean that the gates would be down half the time. “If we were to put a station at the grade, whenever train stopped, the next three streets would need to have the gate down to allow a train to leave the station and continue on its way,” he said. The fact that a Racine station wouldn’t be able to serve the Union Pacific West line is another drawback.

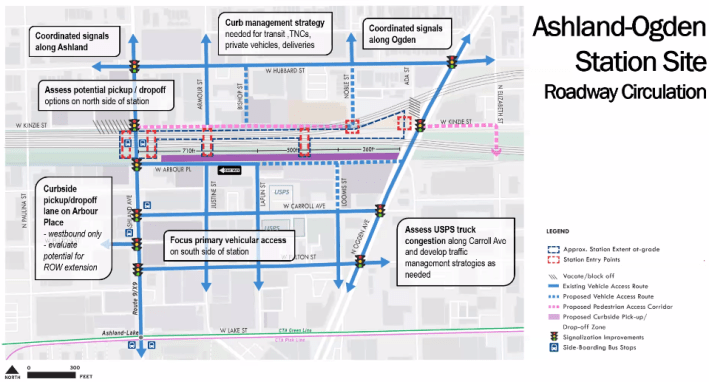

The study settled on Ashland because it is the busiest transit corridor of the remaining three, and the Ashland/Lake ‘L’ station, which serves as a transfer point between Green and Pink lines, is only a few blocks south. But it also recommended doing something similar to the situation at the Metra Electric line’s 55th-56th-57th Street station. The report calls for placing entrances on both sides of Ashland to provide easy transfers to both northbound and southbound buses, and building a walkway connecting the platforms to an entrance at Ogden, and two additional entrances in between: one at Justine Street and one roughly midway between Laflin and Loomis streets.

Another advantage of this location, Sriver said, is the presence of Arbour Place, an alley-like street that runs on the south side of the embankment between Ashland and Laflin. It could be used to stage taxis, ride-hail vehicles, and shuttle buses. He added that Arbour Place used to run as far east as Ogden about 100 years ago, and CDOT would look into restoring it.

As part of the station construction process, the agencies would also widen the Ashland underpass, since it was originally built when the avenue wasn’t quite as a wide as it is now.

Under the preliminary timeline, A-2 interlocking construction would start in 2026, while work on the station would begin in 2028.

Throughout the meeting, officials emphasized that that many aspects of the station, including which lines would stop there and what the station would be called, won’t be decided on until they are further into the planning process. However, Kralik said “the current assumption is that North Central Service trains will serve the station” in order to provide a connection to O’Hare.

During the Q & A portion of the meeting, one resident asked about the possibility of installing displays to clearly indicate which trains are arriving when. In my experience, this has been an issue at the Western Avenue and River Grove stations, currently the only stops where two different lines share the same tracks and, unlike with ‘L’ trains, there is no visual way to tell trains from different lines apart. Sriver didn’t commit to any displays, but promised the transit agencies would try to address that issue.

When asked about property acquisition, Sriver said that it would most likely be necessary one way or another, but added it was too early to discuss the specifics.

Another attendee raised the issue of trains idling on the tracks. Kralik said that some idling would still be necessary “because there are still trains that may need to slow down to get into the yard, or [would need to be] staged to get into the rush hour,” bur he expects that idling would decrease.

Asked about who would own the station, Sriver said that’s a complicated question, since Metra, Union Pacific, and Norfolk Southern own different portions of the property. “It's far too early to say something other than there's a lot of potential options,” he said.

Alderman Burnett, whose ward includes much of the Near West Side, said he hoped that, if the station does get built, it would bring development, while also acknowledging the possibility that development could result in further displacement “I pray that we are able to do those things without hurting people,” he said. “I pray that this is a win-win for everyone.”