Busy roads with fast-moving traffic and an absence of bike lanes – a fair description of most arterial streets on Chicago's South Side – can be dangerous and frightening places for cyclists. For many people, the most intuitive choice for avoiding speeding and/or inattentive drivers in large vehicles, and curb lanes riddled with potholes, is to ride on the sidewalk, but in Chicago that's illegal for people 12 and older. Moreover, bicycling on sidewalks puts cyclists at higher risk of collision, not only with pedestrians, but also drivers, since motorists generally aren't expecting to encounter people biking across driveways or entering the street from the sidewalk. Nonetheless, it can be a more attractive option than being potentially sideswiped by a cement truck driver or attempting to share a lane with cars traveling at 45 mph.

Jason Hardt, who was fatally struck by a hit-and-run driver while riding his bike on Independence Boulevard in North Lawndale, is a tragic, recent illustration of why cyclists might opt to risk a citation for riding on the sidewalk over pedaling on a dangerous street.

During my own commute, heading north on California Avenue in Little Village, the four-block stretch between 35th and 31st streets narrows as it travels under the Stevenson Expressway and over the South Branch of the Chicago River. It feels so treacherous, I admittedly break the law by taking the sidewalk every time I ride that stretch.

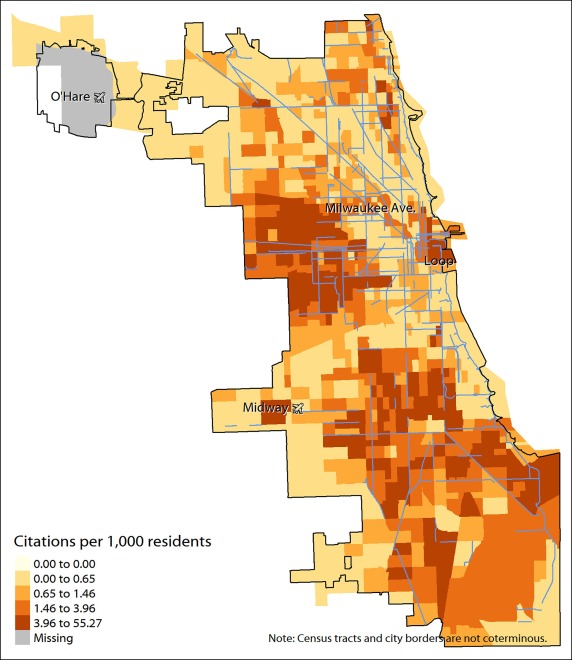

It’s no surprise then that, according to a study by University of California Davis professor Jesus Barajas, tickets for riding on the sidewalk were issued eight times more often per capita in Chicago’s majority-Black communities than majority-white neighborhoods, which tend to have far more miles of marked and protected bike lanes on arterial roads.

In addition, the Chicago Police Department has been fairly upfront about the fact that it uses zero-tolerance traffic enforcement as a strategy to enable searches for guns and drugs in high-crime neighborhoods. “When we have communities experiencing levels of violence, we do increase traffic enforcement,” Glen Brooks, the department’s director of public engagement, said on WTTW's "Chicago Tonight" show in 2018. “Part of that includes bicycles,”

So on top of having to navigate unsafe riding conditions, people riding bikes in African-American communities run a higher risk of being stopped and ticketed by the police. Baraja’s paper, entitled “Biking Where Black” draws a connecting thread between the compounded inequities of inadequate bike infrastructure and disproportionately high level of policing in Chicago’s Black neighborhoods, and how improved bicycle facilities might reduce harm from racially-biased policing.

Barajas' study focuses exclusively on tickets for cycling on sidewalks which, in 2019, made up 90 percent of bicycle-related citations in Chicago. As one might guess, 93 percent of these were issued on streets that had no bikeways. The vast majority of these citations were in predominantly Black neighborhoods – three times more than were issued in majority-Latinx neighborhoods and eight times more than in predominantly non-Hispanic white neighborhoods.

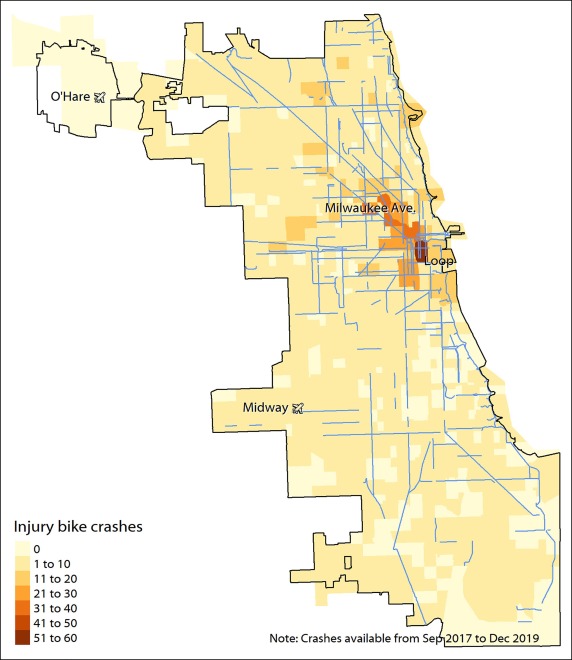

Barajas makes the case that this aggressive level of enforcement has little to do with cyclist and pedestrian safety, noting that “the high number of tickets in majority-Black neighborhoods came despite having the fewest serious bicycle crashes.” Meanwhile the parts of town with the highest numbers of serious crashes – North Side, majority-white neighborhoods with high rates of cycling – had few citations issued.

Barajas found that a high rate of ticketing was most strongly associated with neighborhood poverty. The rate of citations for cycling on the sidewalk rose 3 percent for every percentage point increase in the census poverty rate. He also found the high numbers number of bike tickets correlated with a high number of violent crimes in a neighborhood. He noted that, as mentioned above, the Chicago Police Department has justified heavy bike enforcement in Black neighborhoods as an anti-violence strategy. It's essentially a legal version of “stop-and-frisk” that he argues has contributed to over-policing and undue harm in communities of color.

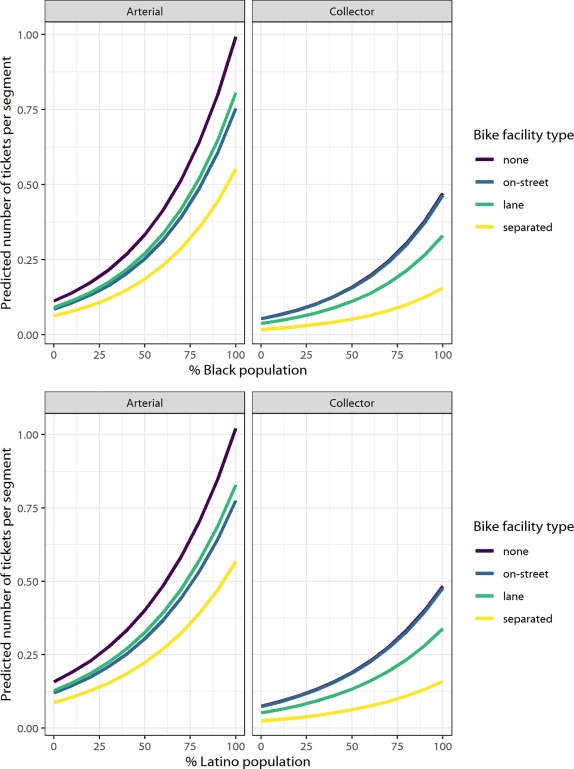

Barajas reasonably postulates that improved bicycle infrastructure – like the surprise Chicago Department of Transportation announcement last week of 100 miles of new bikeways planned for 2021-22, mostly slated for the South and West sides – could reduce citations and to some extent mitigate police overreach by creating safer cycling conditions on busy roads. Using predictive modeling, Barajas calculates that the presence of protected or separated bikeways would cut the number of citations in majority Black neighborhoods in half.

While Barajas doesn’t present bike lanes as a silver bullet to end racially-skewed bike enforcement, he does postulate that they could reduce bicyclist exposure to police action. He writes, “Many sidewalk cycling tickets would not have been issued if the infrastructure associated with improved safety perceptions were available. In this light, bicycle infrastructure might be seen as a tool to advance racial justice…a small but important measure of protection from police overreach.”

Perhaps most importantly, Barajas emphases the importance of community involvement in the planning of new bicycle infrastructure. The crash on Independence Boulevard that killed Jason Hardt occurred after parking-protected bike lanes had been removed at request of residents who were unhappy about the new parking configuration. “Cycling has been seen as a symbol of gentrification in low-income communities of color,” Barajas states. “Removing inequities in cycling infrastructure provision, while also ensuring communities are fully represented in bicycle planning processes, is crucial.”