The city of Chicago is considering turning the little-used portion of Altenheim Line, a CSX railroad owned freight line that runs through North Lawndale, into a pedestrian and bike path, similar to the Bloomingdale Trail, aka The 606.

The city is looking at the section of the line between Kostner and Califoria avenues, which runs on an elevated embankment roughly mid-way between Taylor and Fillmore streets. Ald. Michael Scott (24th), whose ward includes most of North Lawndale, said that he’s been interested in turning the line into a trail for the past few years.

On August 12, he, along with Chicago Department of Planning and Development and the North Lawndale Community Coordinating Council, held a community planning session at Douglass Park field house, located about four blocks south of the rail line, to get input from residents about what they’d like to see on and around the trail. Around 20 people attended over the course of two hours. As officials emphasized several times, the planning process is still in preliminary stages. Two more meetings will take place in the fall, and the final report isn’t expected to be completed until January 2022.

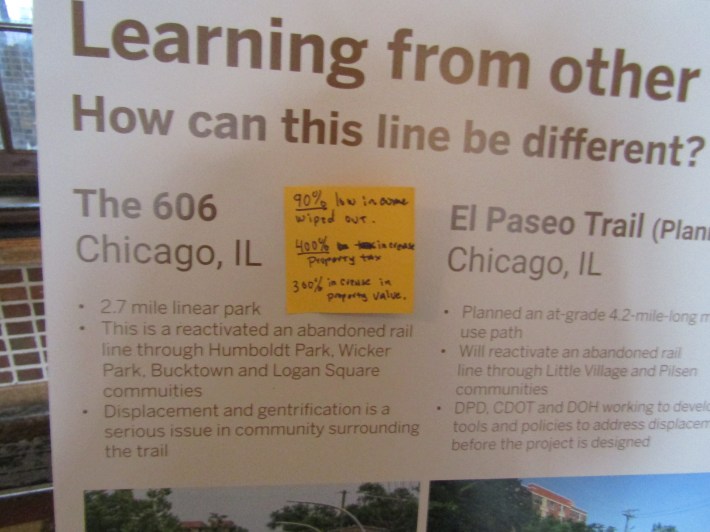

While the officials touted the trail’s potential to spur development, they acknowledged concerns that while the new amenity would increase property values, it could also lead to higher property taxes and housing costs, and housing displacement. Scott said that the city learned its lesson from the Bloomingdale Trail situation, and he argued that displacement would be easier to avoid near the North Lawndale greenway because the amount of city-owned land near the trail would give the city more leverage in shaping development.

The Planning Process

The rail line was originally built by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in 1893, going as far west as the present-day Altenheim retirement community in Forest Park. The line served several factories and warehouses in North Lawndale – most notably, the Sears, Roebuck and Company’s campus. The line had commuter service, but it lasted less than three decades. While the western portion of the line gets regular use, DPD staff said that the North Lawndale portion is used an average “once or twice a year.”

Scott said that, not long after he was first elected alderman in 2015, he toured the redeveloped Sears campus. As he looked at around from the top of North Lawndale's Sears Merchandise Building Tower, the original Sears Tower, he saw the rail line cutting through the community.

“I needed to know what was going on with that line,” Scott said. “Since then, I’ve been on the mission to get this done.” The alderman said that he didn’t get much traction until Maurice Cox was appointed Planning and Development Commissioner in Oct 2019. But it still took the better part of two more years before the study kicked off this summer.

The North Lawndale Community Coordinating Council is a coalition of North Lawndale community organizations, institutions, business owners, community activists, and other people involved in the community. Jesse Green, the organization’s senior director, said that as soon as the council heard about the proposal, they wanted to get involved.

Green added that NLCCC wanted to make sure residents were involved early on. “Oftentimes, what happens in the community is that people don’t get engagement until after the design has been completed, and we don’t want to do that approach."

Green said that NLCCC assembled a committee made up of “renters, homeowners, business owners and youth” to work with the city on the trail design and review feedback from outreach events. “This isn’t one and done – this is a repetitive engagement process that is transparent and inclusive."

NLCCC shares its regular committee meeting schedules and Zoom access information through its newsletter, but planning committee meetings haven’t been included. When I brought that up, Green said that while he never thought of it before, posting video recordings of the meetings online would be a good idea.

During the planning session, residents were asked to comment on what kind of development they would like to see around the rail line, including what kind of art and recreational amenities they're interested in. Adding a grocery store was a recurring theme, as were community gardens, historical installations and recreational spaces such as skate parks.

Attendees were even asked to suggest trail names. Brian Hacker, DPD’s West Side coordinating planner, said they are simply using the existing Altenheim Line name, but they would go with whatever the community wants. Some of the suggestions included “Peace Trail,” “Lawndale Trail” and several variations of “OutWest Line”

Theresa Thomas, of North Lawndale, feels the trail idea has potential. “It would keep us connected as a community, because it would give us more things to do. It will give us a new perspective. Sometimes, when people get something new, it makes them feel good.”

Tito Cantres, of North Lawndale, said that he grew up near the Bloomingdale Line before it was converted into the trail. He was leery because he recalled the line being dangerous and he didn’t want the Altenheim trail to become “a highway for gang members” crossing gang territories and evading police. But he added that it could be avoided with community involvement. “I am also optimistic, because [the trail] could help economic growth and improve the neighborhood."

Displacement Concerns

The planning process kicks off amid several efforts to bring development to North Lawndale. As part of the city's Invest South/West initiative, DPD is soliciting redevelopment proposals for the former Silver Shovel dump site at the west end of the proposed trail, as well as the seven lots along Ogden Avenue, between Homan and Trumbull avenues.

At the same time, Scott has been working with several developers to build homes on city-owned vacant lots throughout North Lawndale through the City Lots for Working Families program. Most notably, Lawndale Christian Development Corporation and Pullman-based Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives are trying to build 250 homes.

One challenge has been that the city's definition of affordable housing is based on the Area Median Income for the entire Chicagoland region, which puts rents out of range for most North Lawndale residents. LCDC would try to address this issue through housing subsidies. But Scott and the developers said that one of the goals is to attract new residents to make up for decades of population loss, and many of those newcomers may be more well off.

Developments involving city-owned land are automatically subject to the Affordable Requirements Ordinance, even if the developer isn’t getting city funding or asking for a zoning change. The city can also attach covenants to the land sale. The current version of the ARO also incentivizes putting affordable units in gentrifying communities.

“When the developer approaches us, we're going to make sure those things are community-friendly,” Scott said. “If you’re going to erect things that displace folks, that’s not something I’m going to support.”

Green believed that the alderman’s approach would work, adding that avoiding displacement is a major priority for NLCC. “The goal of this program is to ensure that the existing homeowners stay in their homes,” he said, adding that his organization is working with the Chicago Department of Housing and Richard Townsell, LCDC director and chair of NLCCC’s housing committee, “to come up with strategies for how we can mitigate displacement.