For the last two years, Chicago has hosted pilots of rentable dockless electric scooters, and the city released an evaluation of the 2020 pilot last May. An ordinance proposed by 21st Ward alderman and Transportation Committee chairman Howard Brookins (who made national headlines after he was seriously injured when a squirrel jumped into the spokes of his bicycle) seeks to make the scooters a permanent part of Chicago’s transportation system. The legislation would authorize licenses for three vendors to each deploy 2,500 scooters across the city, for a total of 7,500. That's the same number of vendors that participated last year – Bird, Lime, and Spin – but fewer vehicles than the total of 10,000 that were allowed during the 2020 pilot.

The ordinance states that scooters must be "lock-to," that is, equipped with built-in locks for securing them to bike racks or poles when not in use, as a strategy to help prevent sidewalk blockage and vandalism eyesores. Last year’s pilot introduced a lock-to requirement and according to the Chicago Department of Transportation, 311 complaints related to e-scooters decreased 75 percent from 2019 numbers. Nonetheless, several aldermen have expressed opposition to permanently allowing scooters in their wards, complaining that the vehicles were still a nuisance due to issues like sidewalk riding and right-of-way clutter.

Brookins said he would ultimately like to see corrals for the scooters, akin to Divvy parking stations, but that the city needs to commit to a permanent program for vendors to invest in the parking infrastructure. “Some of the concerns my colleagues have are scooters being littered on the street with no corral to put them,” he said. “I do understand these complaints. The pushback from the scooter companies is, ‘We can’t build out all the infrastructure to properly store them unless we know we’ll be there.’”

Sidewalk riding is a nuisance and hazard to pedestrians. According to Spin spokesperson Jay Ibarra, the company is piloting a new "sidewalk detection technology" system that uses artificial intelligence and and computer vision to detect whether users are riding on the sidewalks and if they are parking scooters correctly. "If it detects that a rider is on the sidewalk, it’ll make an audible sound to tell the rider to go back into the bike lane."

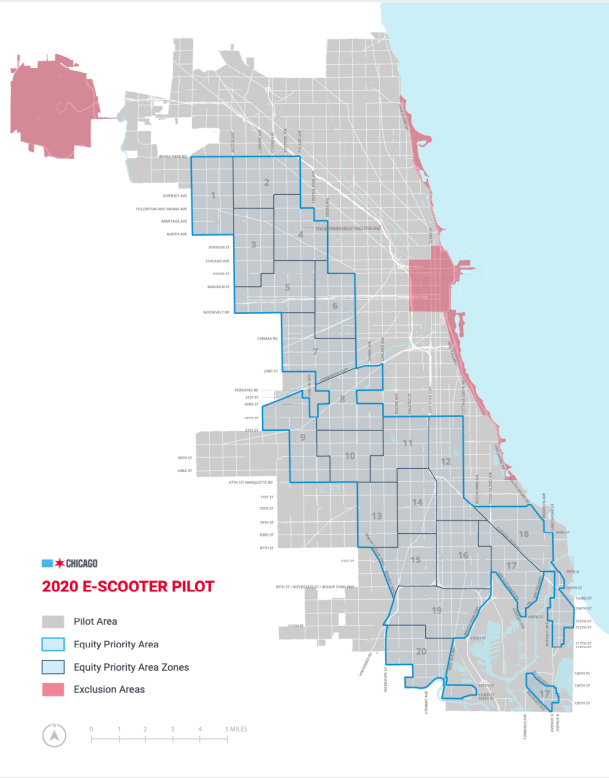

The proposed ordinance requires that all scooters have geo-fencing technology to prevent riders from taking them into prohibited areas, which last year included downtown and the lakefront. Safe riding instruction, including learn-to-ride classes and in-app education would also be a requirement. Scooter use would be restricted to the hours of 5 a.m. and midnight.

Brookins said he believes the scooters are a tourist attraction and he wants to see them available in the Loop for both transportation and recreation. “I think these micro-mobility devices are gateways to the future,” he said. “[They're an efficient and low-cost means of transportation to get to the bus stop, or to get from the Bean, to the Museum Campus, or North Michigan Avenue – and get some of the automobiles off the road.”

The 2020 pilot required vendors to distribute half of their fleets in Equity Priority Areas on the South, West and Northwest sides, which together comprised 45 percent of the total pilot area. Despite relatively equal distribution, with 92 percent of equity areas within a 5-minute walk of a scooter, ridership remained concentrated on the North side, and just 23 percent of rides took place in equity areas.

However, both Brookins and Claffey said this number demonstrates citywide demand. “The companies will be required to distribute scooters on a citywide basis, with a focus on serving equity areas, as defined by CDOT and [the Chicago Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection],” Claffey wrote. “And the scooter companies will be required to implement at minimum scooter access for pricing programs for low-income and unbanked Chicagoans, as well as access for those without smartphones.”

Brookins said that he believes scooters will be more widely adopted once they’re consistently available. “I think as [the vendors]... figure out the market they’ll get better at it. Anecdotally I see younger riders on the scooters and they seem to have fun with it. When people figure out where they’ll be and how to get them and that they’re reliable, more people will try them.”

Brookins said he believes the ordinance will pass and shared e-scooters will become a permanent part of Chicago’s transportation system by next year. He looks to scooter sharing in other cities as evidence they can and should work in Chicago, too. “I really think if we get creative and really plan out the modes of transportation for the next 50 years we can make this the city of the future as opposed to trying to catch up from behind,” he said. “If Memphis and D.C. can have scooters I think we can figure it out.”