A consultant by day, Richard Day serves on the board of Renaissance Social Services, an affordable housing provider in Chicago (the opinions expressed here are his own.) He lives in Logan Square and is on a mission to find the best hot dog in the city.

As Chicago recovers from COVID-19, many of the scars have only begun to heal. One of those scars is on our transit system: CTA ridership collapsed during the pandemic.

Without a strong recovery, rail and bus service could enter a ‘death spiral’ as lower rates of ridership cause revenue to fall. Declining revenue would create budget shortfalls prompting service cuts. Those cuts would result in less frequent bus and train service, and ridership would falls even further, creating a vicious cycle. Many transit users who could afford to do so would ditch buses and trains for private cars and ride-hail, leaving less-affluent riders stranded with worse service than ever, and our city and climate would suffer as a result.

Fortunately the worst of the scare is over. CTA riders are starting to come back, and the federal government is providing support via the American Rescue Plan to help avoid service cuts in the short term. But we’re not completely out of the woods yet. With more people working from home and behavior patterns altered by more than a year of social distancing, it’s unclear how well ridership will recover.

Of course, this process can also work in reverse: If ridership goes up, that means more revenue for transit, which could be used for further investments in the CTA, which would attract more riders, creating a virtuous cycle. Better transit supports even more riders, and a more equitable, healthy, and sustainable city.

So how can we get more riders back on our trains and buses?

People ride transit when it’s nearby

It sounds obvious, but people take the train or bus when it’s more convenient and cost-effective than the alternatives. Of course that means transit needs to be safe, run frequently, and be reliable. But, if it’s not near where people live, none of that matters.

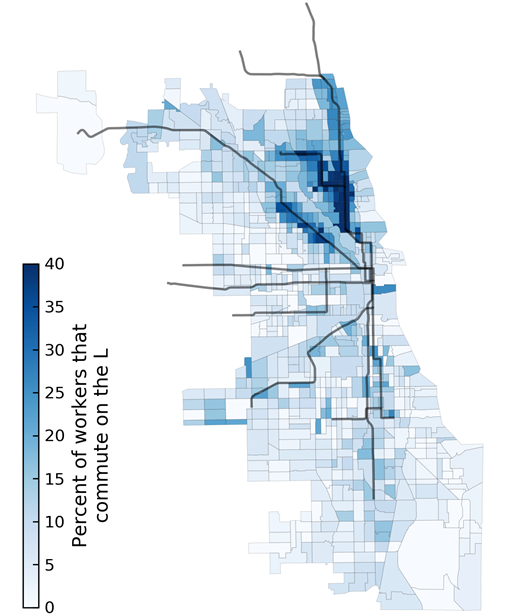

Here’s a look at the percentage of Chicago residents who took the ‘L’ to work pre-pandemic, by Census tract. Ridership drops off dramatically as people get further away from train lines.

There are a range of reasons for the discrepancies between the North and South sides on this map. As previous Streetsblog contributor Daniel Kay Hertz has noted, lower population density, a higher share of bus ridership, and a smaller share of workers commuting into the Loop likely account for the lower ‘L’ commute share on the South Side. But across the city the picture is clear: Chicagoans are much more likely to take the ‘L’ if they live nearby.

And while we need to continue to invest in better transit access, especially on the South and West sides, this map also highlights another approach we can take right away to help the system recover: We can build more housing near the transit we already have.

Better development supports better transit

Denser developments near transit lines can help support a stronger transit system for everyone. People who move next to an ‘L’ stop or bus corridor are much more likely to be consistent transit riders, especially if the development includes relatively modest amounts of on-street parking (which also help keep those apartments more affordable.) In the suburbs, individuals who moved to areas around Metra stops were a third less likely to drive to work alone, from 44 percent to 30 percent.

We’ve already seen promising results from Chicago’s Transit-Oriented Development projects. Since 2012, the city has begun to offer benefits to encourage developments near transit. Between 2012 and 2018, 90 percent of the ‘L’ stops that had ridership growth were in areas with transit-oriented development activity. And that’s just the start. As the city’s Equitable Transit-Oriented Development Policy Plan notes, we can do much more to encourage more equitable development across the city. That includes offering higher density bonuses and waiving expensive parking requirements. In particular, equitable transit-oriented development (eTOD) on the South and West sides could help bring greater density and job opportunities to existing transit lines.

But while transit-oriented development is a good start, the city’s TOD program only yielded 150 new projects between 2013 and 2019. And even as a small number of projects get through, 45 years of efforts to downzone the north and northwest sides have excluded a growing share of Chicagoans from high opportunity, transit-rich neighborhoods. In the process, the very people who would benefit the most from better transit access (particularly lower residents and Chicagoans of color), are priced out.

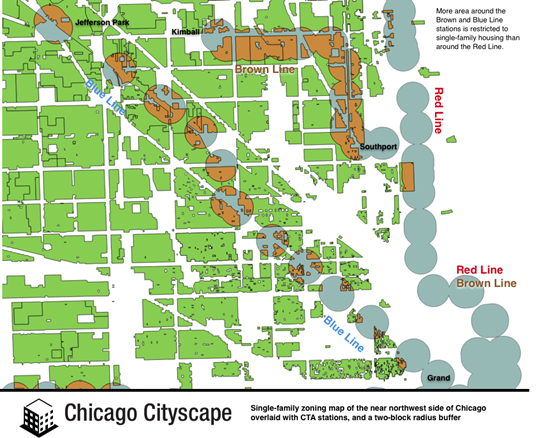

An analysis by Streetsblog Chicago co-founder Steven Vance found that on the North and Northwest sides of the city, much of the area around the Blue and Brown stations has been restricted to single family homes. Areas zoned exclusively for single family homes within the two blocks around ‘L’ stops are highlighted here in brown:

In fact, Vance found that 20 percent of the land within two blocks of CTA and Metra stations across the city is exclusively zoned for single-family homes. Even a slight up-zoning (to two- to four-flats, or courtyard apartments) could dramatically increase the number of people living near (and using) transit.

To secure the future of transit in Chicago, we need to think bigger. In addition to pushing forward with the city’s eTOD plan, we need to update the zoning code to allow two-flats and low-rise apartments near transit in neighborhoods across the city. Not only will that strengthen our transit system, but it will help ensure a more equitable and affordable city for all Chicagoans.