When it comes to models of what a cycling culture looks like, the Netherlands is the most often used example, at least in North America. Yes, the Netherlands has achieved impressive stats on the number of trips made by bike and the representation of women and children using bikes for mobility. However, there’s still a lot to learn from other parts of the world as well.

A little over two weeks ago the Metropolitan Planning Council hosted a discussion titled, “Building Bike Culture: Lessons from Latin America Can be Applied in Chicago.” The discussion was sponsored by Divvy and HDR. Lynda Lopez, advocacy manager for the Active Transportation Alliance, moderated the discussion. Featured speakers were Iván de la Lanza, a sustainable urban mobility specialist with the Sur Institute in Mexico City; Rodrigo Sandoval Araujo, chief of communications for the department of parks, recreation and sports, in Bogotá, Colombia, and Pha'Tal Perkins, founder of Think Outside da Block here in Chicago.

Lopez started off grounding the discussion by sharing that Spanish-speaking countries are often not centered in conversations about biking. Lopez went on to say that by expanding our ideas of what a biking culture looks like we can increase the potential for positive change. Lynda shared her story of learning to ride as a young child and bike commuting after graduating high school. Lynda shared that the recent death of Kevin Clark could spur demands for safe biking infrastructure, but it could also scare people away from biking. “There’s now an added weight when choosing to ride in the city.”

Lopez posed the question, “What does it look like to demand better on our streets for people on bikes?” She spotlighted the needed work to bring more protected bike lanes to Chicago and ended by discussing her hopes for the future. “There’s much work to be done to realize the vision where people can safely bike in our city streets. I hope that learning from perspectives from across the world will spark ideas on what we can do differently. I love biking. It makes me happy. It also fills me with fear. I wonder what it looks like to have mobility without so much fear of the implications of riding on certain streets. I also hope for a day where Black and Brown neighborhoods are prioritized in getting infrastructure improvements and access to bikes.”

Pha’Tal Perkins of Think Outside da Block was the first panelist to present. He shared a compilation of photos and video taken at Roll N Peace community bike rides. Roll N Peace has been the most successful event Think Outside da Block organizes according to Perkins. The 2020 ride was just a few weeks after the murder of George Floyd and attracted over a thousand participants.

Perkins was initially inspired to create Roll N Peace after reflecting on his childhood memories of riding bikes with friends. Perkins has heard from many Roll N Peace attendees that the event was their first time riding a bike. He spoke of two barriers that can hold people back from biking in Englewood: concerns about being hit by a driver while riding and worries about street violence.

Perkins discussed the challenges in creating better cycling infrastructure in Englewood during his time as a Mayor’s Bicycle Advisory Committee representative due to the community having multiple aldermen. Perkins was asked how he sees biking as an avenue of social change in his community. He responded, “I know there’s a common perception that Black people don’t bike or bikes are for kids. I’ve found just by organizing Roll N Peace we’ve been able to change the narrative about Englewood. So many people have shared that Roll N Peace was their first time visiting Englewood and that it wasn’t as bad as they thought. After our second Roll N Peace ride, the police commander for the district that includes Englewood informed us that there had been zero reports of violent crime in the entire district on the day of the ride.”

Lanza shared a presentation on active mobility in Mexico City with a focus on building a more equitable city through cycling. Iván started off his presentation stating some of the challenges cities face: projected population growth, growing numbers of cars, which causes an increase in negative externalities, COVID-19, and climate change. “The decisions we make today will determine whether cities can grow while improvising citizens’ quality of life or perpetuate that cycle of low productivity, poverty, and environmental degradation.” Lanza shared a graph showing the technical feasibility of cities reducing emissions by 2050. The conclusion? Cities can be powerhouses for change, especially when it comes to reducing transportation emissions.

Audience members were provided stats on global rates of active transportation. Twenty to 65 percent of all trips around the world rely on walking or cycling. Many more trips begin or end with walking and cycling. Active transportation provides a variety of benefits linked to sustainable development goals. Unfortunately, many people have had their lives risked or ended while using active transportation. More than 1.3 million people are killed while walking or cycling each year. By improving walking and cycling conditions, cities provide a sustainable and healthy way to access education, health, development, and public space while reducing inequality. According to Lanza, Latin American cities have very unequal access to public spaces. He sees biking as one avenue in which people can become more engaged in their city and have more connection with one another.

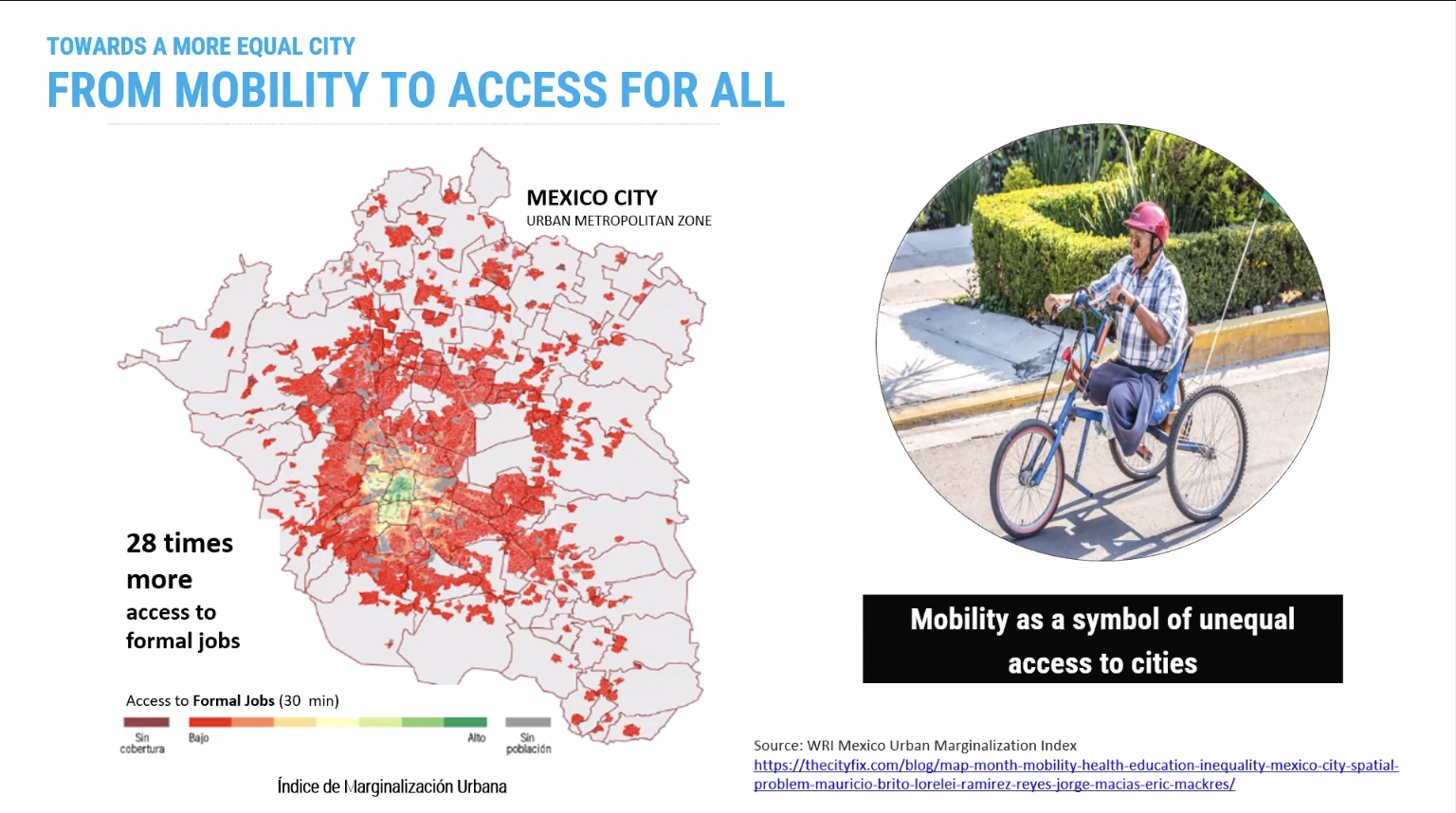

In Mexico City, residents in the central zone of the city have up to 28 times more access to formal jobs than other residents. Mobility modes can symbolize unequal access to the city. Fifteen years ago Mexico City developed the Bicycle Mobility Strategy which relies on three main pillars: culture and education (an Open Street program and Bike Schools), Infrastructure and Equipment (bike lanes and bike hub networks), and the ECOBICI program, Mexico City’s bike share system. ECOBICI, which debuted in 2010, was designed to be well-integrated with the public transportation system. During a 2017 earthquake, the Metro system was down for several weeks. Bikes filled in some of the gaps during that transit shutdown.

I was impressed by the concept of a bike hub. Essentially they’re covered garages for people to park their bikes when they use transit. I found the before and after image of the space used for one hub to be pretty cool.

Sandoval Araujo provided context for biking in Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, which has over 8 million residents in a mountainous and rainy environment. Many of these residents own bikes and that’s not by accident. Only thirty percent of Bogotá residents own a car. For over forty years there’s been a growing movement to make bikes a part of the urban fabric in the city. Since 1974, there has been a regular opening of the streets to bikes, skating, walking, etc. The weekly open streets events happen on Sundays and are called the Sunday Ciclovia ("Bike Path."). The Ciclovia was organized by Jaime Ortiz Mariño, who was able to recruit other passionate cyclists for the scheme. In the late 1970s then-mayor Luis Prieto Ocampo made the Ciclovia became an official program promoted by the City government and supported by the Transportation Department. The Ciclovia has spurred similar events across the world.

Along with regular street openings to support active transportation and recreation, Bogotá offers some incentives for bike commuters. Sandoval Araujo actually drafted the legislation which led to these incentives. He admits the bill is not as good as it can be but there are some nice incentives. For example, public parking lots must dedicate at least ten percent of the space to bike parking. Public servants can apply for a paid half day off work for every 30 days they commute by bike. Every new road project must include separated bike infrastructure.

Currently, around ten percent of Bogotá commuters use a bike for their commute. Bogotá has over 800 kilometers (497 miles) of separated cycling infrastructure, about the same mileage as the distance from Chicago to Nashville. Bogotá is building 300 km more of separated cycling infrastructure in the next two years. This year Bogotá created The Bike Public Policy which is a guide document that will guide a six hundred million dollar investment on biking policy for the next ten years. These investments will lead to a public school focused on creating new technical knowledge around biking, new bike paths, research on public biking, and the creation of a public bikeshare system. An investment like this was possible due to a strong social movement around biking and the prioritization of biking among elected officials.

However, despite the strong social movement and government support, there’s still a large gender gap when it comes to cycling. Sexism in Latin America has led to many young women not being taught to ride a bike. Myths about riding a bike leading to loss of virginity and ideas about acceptable social behavior for young women have held back potential women cyclists.

The city of Bogotá has created women-only cycling classes where women can come and learn how to ride a bike. These classes are available six days a week. There are even classes specifically for older women. (Here’s an article highlighting the push to get more women on bikes in Bogotá.)

I learned that Bogotá has “Manzana de cuidados," which are structures that house parks, schools, and public laundry (!!!). These centers are the site of biking classes for older women. For those concerned about their safety as they cycle, there are “bike to work” events that employ police and public servants who lead rides for commuters. Lastly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Bogotá created temporary separated bike lanes as a way to reduce people’s COVID exposure on public transportation.

During the Q & A , and attendee asked increasing the number of women and children who bike. Perkins said he believes in making biking fun through strategies such as holding contests for who has the coolest decorated bike and offering prizes. While I definitely agree making biking fun is a strategy for attracting more children, safe infrastructure is key.

Lanza highlighted the importance of safety and the inequality of road deaths. Those who are lower-income are more likely to be killed in traffic crashes. He said, “We need to design the roads to be safer.”

Sandoval Araujo pointed to the bike to work program which provides an opportunity for cyclists to form commuting groups. The idea is that there is safety in numbers. He later added that while relations between government and social movements are not always easy, the communication between the two allows policymakers to respond. He cited an example of women’s rights organizations reaching out to transportation policy makers informing them of areas that women highlighted for needed safety interventions. It also helps that the leader of the Ciclovia program is a woman who rides the streets every day.

Presenters were then asked how equity, particularly economic equity, has been woven into biking culture and initiatives in order to create a ridership that is diverse economically. Sandoval Araujo said there are difficulties in building bike paths in poor neighborhoods. He noted that twenty years ago a 22o kilometer (thirteen miles) bike path was built in Bogotá, which leads from a poor neighborhood to the industrial area. When the path was first built, there was no development. Afterwards development followed. He encouraged policy makers to see biking infrastructure as a development tool.

Lanza reiterated that mobility is a symbol of inequality across the world, in that that different travel modes result in different access or mobility levels. For example, those who primarily walk will have lowered mobility versus people who drive. Lanza wants cities to see bike infrastructure and bike-share systems as an investment in their citizens as opposed to subsidizing a niche group. Given the low cost of bike-share for users (ECOBICI only charges one peso for forty five minutes which is equivalent to ten US cents) and its ability to provide first- and last-mile trips to and from with public transportation, Lanza sees an investment in the expansion of ECOBICI and bike infrastructure as a smart choice.

Watch the full discussion here.