Since 1982, public transportation has been financially hamstrung by the Highway Revenue Act, which allots 80 percent of federal funding to roads and at most 20 percent to transit. Our car-centric culture, which accelerated in the 1950’s with the construction of the Interstate highway system that ripped through Black and low-income neighborhoods, was further cemented by this Reagan-era funding split, which effectively increased car dependence and essentially ensured that public transportation systems would fall into debt and disrepair.

Advocates believe a bright spot is on the horizon, with the current surface transportation act set to expire this September under President Joe Biden and transportation secretary Pete Buttigieg, who have both voiced support for public transportation. It's a rare alignment of politics and policy cycle that could shift the funding imbalance and transform an unjust transportation system nationwide.

Illinois Congressional representative Chuy Garcia, along with reps Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts and Hakeem Jeffries of New York, put forth a resolution last December for transit parity: equal federal funding for highways and public transportation. Last week, the national advocacy group Transportation for America hosted a panel discussion with New York-based Riders Alliance policy and communications director Danny Pearlstein, Atlanta-based urban planner and transit advocate Bakari Height, and Dr. Beverly Scott, who has served as head of four major transit agencies across the country, to discuss what funding parity would mean for transit and how to get there.

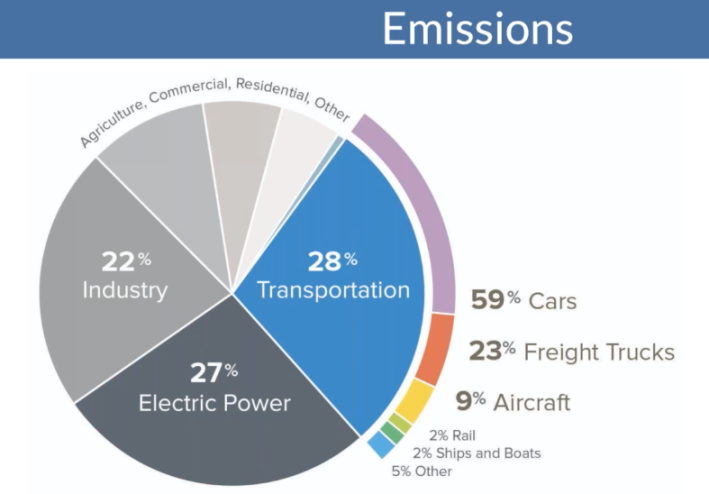

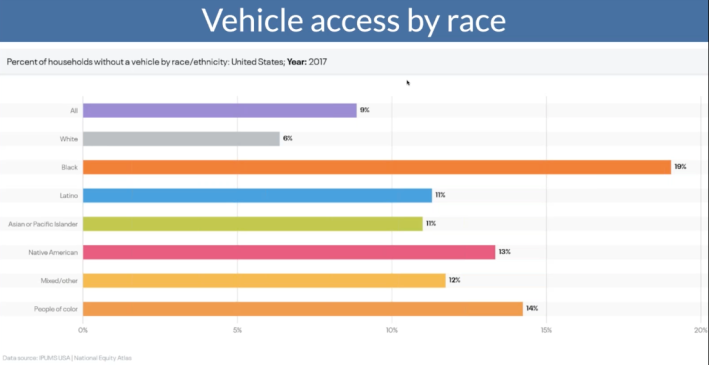

The conversation was moderated by Transportation for America policy and communications associate Jenna Fortunati, who opened with slides illustrating the environmental impact of the transportation sector – currently the largest source of greenhouse emissions, over half of which are spewed from cars – and the racial disparity of households with access to personal vehicles.

Fortunati asked Scott how the longstanding federal funding split affected her ability to deliver service as a leader at several transit agencies, including the Sacramento Regional Transit Authority, the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, and others. Scott said the real, underlying problem of public transportation in the United States is not so much a scarcity of dollars as a poverty of imagination. She said the country needs a vision for transit as bold and sweeping as the federal highway act that built the interstate system and tied the cultural imagination to personal car ownership and the open road. “Let’s get the money right," she said. "But this is tied to a bigger thing: a lack of vision. The American Dream of the 1950’s – "Leave it to Beaver" – is unsustainable. If we can get clear on the outcomes we want, then the dollars flowing, we can get cooking on all cylinders.”

Scott pointed to Europe as a model of visionary transit planning. “They were intentional about having transit systems of first choice, not last resort…we think of building transit for someone else to use. We need to think about building a system I will use, that my friends and family will use.”

Height noted that a truly sweeping and inclusive vision for transit needs to extend beyond dense urban areas. He noted that, as gentrification pushes people who rely on public transportation out to the suburbs, service must expand, and applauded Amtrak’s plan to expand intercity rail. The proposal was spurred by Biden's rail-friendly $2 trillion American Jobs Plan infrastructure package, which includes $80 billion for Amtrak.

An audience member asked how lawmakers can be convinced to support funding parity, which would have a particularly big impact in cities like Birmingham, Alabama. Birmingham receives no funding for public transportation from the state and therefore its bus system has seen severe budget shortfalls and service cuts.

Height replied that attracting big business can spur demand for transit investment, citing the new Microsoft hub in Atlanta, which coincides with the biggest investment in MARTA since its inception. He also mentioned the crucial role housing policy and developers play in creating a convenient, accessible and equitable public transportation system. “If you can’t show people how they can use transit in their lives, they won’t fund it. You have to show how it’s as much of an amenity as being close to a river or a mountain.”

When it comes to changing hearts and minds of lawmakers, Pearlstein also pointed to the problem of transit being perceived as something for people who can’t afford a car – even in New York City, where 55 percent of households are car-less and 60 percent of residents use the MTA. “Many lawmakers feel like they’ve graduated from transit. They have higher paying jobs and can afford to buy a car. What they often don’t realize is how many of their constituents rely on it.”

All the panelists agreed that connecting representatives with the real-life stories of their constituents is the most powerful way to build support for funding transit. Scott invites members of Congress to take a bus ride with one of their constituents. Height looks to coalition-building, finding the stories that resonate, like the streetcar that stops in front of a neighborhood church. Pearlstein takes inspiration from advocates for people with disabilities. “Inaccessibility is a travesty. But it hasn’t stopped a coalition from demanding change. We’re seeing elevators built where they weren’t believed to fit.”

“The democratic process is not a spectator sport,” Scott said. “There is progress, but changing the status quo and institutions takes focus, attention and consistency.”

To ask your representative to support equal funding for transit and highways, visit Transportation for America's website.