Last week, the Washington D.C.-based urban planning nonprofit Smart Growth America held a three-day virtual summit about improving racial equity and taking action on restorative justice in housing, business development and transportation. Day three, dedicated to the latter, centered around the environmental, health, and economic damage inflicted by the interstate highway system, envisioned in the 1950s and '60s as massive urban renewal projects which, in actuality, razed homes and businesses, displaced residents, carved up neighborhoods, introduced massive amounts of concentrated auto emissions into neighboring predominantly Black and Latino communities, and created a high-speed conduit for white flight to the suburbs.

The day began with an introduction by Smart Growth America CEO Calvin Gladney, who summarized three emergent themes from the previous days. One, that to talk about racial equity one must address the racism of past infrastructure decisions. Secondly, as Gladney put it, “our fates are tied,” in that equity is economic stimulus improving outcomes for all. And thirdly, that ending the harmful policies of the past is not enough and plans must include repairing the damage of past wrongs.

These themes continued to resonate on day three during a panel discussion moderated by Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America. Osborne opened with a policy proposal forwarded by T4America and Third Way to “undo the damage of ‘urban renewal.’” The title slide was an aerial photo of the Eisenhower expressway facing due east, the Willis Tower and lake Michigan providing an iconic backdrop to the 14-lane expanse of concrete where vibrant Greek, Italian and Jewish neighborhoods once stood.

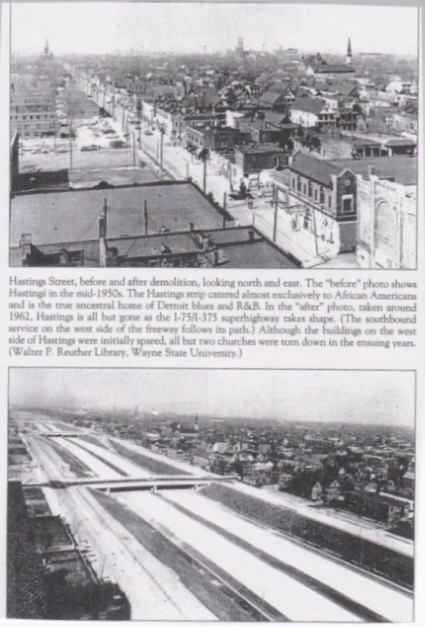

Osborne noted that these kinds of highway projects displaced over a million people nationwide, particularly in Black neighborhoods, sharing dispiriting before-and-after photos from Atlanta, Detroit and a more recent highway development in Kansas City. Osborne added that, ironically, much local economic activity was decimated by these projects intended to renew urban areas, which “serve the needs of people passing though, not those on the ground. She added, "Everyone agrees infrastructure is a priority. But we want projects that sustain and develop strong communities. If we aren’t strategic, we’ll have more problems: exacerbated racial inequities, more pollution and harm to health and economy.”

The T4America and Third Way initiative calls for a $10 billion grant program to fund community proposals for infrastructure change; land trusts to help local residents buy property; updates to U.S. Department of Transportation modeling tools; and a requirement that federal agencies issue guidance on prioritizing resources to communities where they’re needed most. T4America proposes these recommendations be included in a COVID-19 infrastructure package or as stand-alone legislation. A grant of this size could go a long way to improving infrastructure in impacted communities, and the question of the day was, what does community-based urban planning look like? How can community members, urban planners and legislators effectively take action and make positive change that redresses damage from top-down decision-making of the past?

Osborne then introduced the three panelists for the day: Dr. Destiny Thomas, founder/CEO of L.A.-based urban planning collective Thrivance Group; Minnesota State Representative Rena Moran; and Melvin Giles, a community leader in the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul, an African-American cultural hub that was cut in two by the construction of I-94.

Osborne argued that contemporary urban planning is still tainted by the bad decisions of the past. She said it's necessary to identify aspects of transportation planning that “move us unintentionally toward more inequity and pain?”

Thomas said she didn’t agree that inequitable consequences of modern transportation planning are unintended. “Transportation in this country is about appeasing white comfort,” she said. “Highways were built to serve white people in suburbs uncomfortable living beside Black people in urban centers. We’ve addressed density, but not overcrowding from ghettoization in Black and Brown communities. We need to have Black practitioners at the table for policy and funding… There’s a lack of lived experience and cultural know-how and empathy at tables where these practices stem from."

Thomas added that with "multiplicity of need and despair in Black communities," we need to think from interdisciplinary perspective. “Take the bus shelter: Why isn’t it providing high-speed internet? Why don’t we want it to provide shelter for people experiencing homelessness? Why can’t bus stations be places to get fresh produce?”

When Osborne asked how advocates and legislators could make community engagement around transportation issues easier and more user-friendly, Giles drew a bubble wand from a plastic container and blew a stream of iridescent spheres toward the screen, his face beaming. “Joy,” he said. “Get out of our heads and into our hearts.” Giles added that he is grateful to organizations doing the policy work he, and probably most people, find boring.

Giles discussed an inspiring example of residents literally coming to the table around a transportation issue. “In 2014, when light rail was going to cut through the neighborhood, we had the vision of [Create: The Community Meal] a half-mile table, 2,000 people gathered around, hundreds of volunteers serving food, those volunteers were dancing. Sharing food, growing food. Go where people are.”

Thomas gave an example from her own organization. “We were able to bring planning to community in a way that wasn’t transactional. We invested in long-term relationships, spending eight hours per day every day with community members. As planners we weren’t trying to grapple with what community wanted, and the community wasn’t trying to grapple with language we used.” Thomas also emphasized the importance of partnering with social safety net agencies like WIC, which understand community needs, and including them in planning exercises and charrettes.

When asked how to best communicate the benefits of new approaches and sway individuals resistant to change, Giles replied that it takes skill, training, and for all parties to let go of guilt and blame. “This is about healing,” he said. “We need to stop pointing fingers.”

Thomas argued that too much negotiation around mobility issues has already taken place. “We have negotiated too much around human decency," she said. "Think of how irrational it would seem if your city had to pass five ordinances just to get water flowing through a pipe. Water is a pubic utility. Transportation is a public utility. Sometimes the majority does not know what is best, particularly for the people receiving the short end of the democracy stick. The democratic approach in transportation planning has not worked. We need bold, willing leaders to step in and do what needs to be done.”

Moran noted that willing leaders in government are usually spurred to action by their constituents. “Every movement has been created from people standing up and marching," she argued. "It hasn’t been created by an elected official creating the change—they’ve been forced into it. It’s about organizing, about a collective vision.”

Thomas saw need for visionary top-down action at the city and federal level as well. “These cities and municipal agencies know how to override the will of a majority. They do it in Black neighborhoods all the time,” she said. “So use the mechanism you’ve been using, but do it to benefit a different community this time."

Thomas also argued that transportation investments in previously disenfranchised communities of color should be referred to as reparations. "[That] sets the tone and agenda for how we resource this and bring it to scale," she said. "What I would not like to see happen, is what we saw with rollout of high-speed internet, when we began to name the digital divide before it was rolled out. We’ve been good at naming and foreseeing what the harm will be, and less invested in preventing it from happening. This has to do with who we allow to sit at the table and lead these processes.”

The Smart Growth Equity Summit laid out a vision for racially equitable transportation planning: a process that brings together technical experts, residents and elected officials in candid conversations that assess errors of the past and the needs of the present, and envisions the future in a spirit of trust, celebration and healing. It's a process that brings together advocates for healthy transportation systems, food systems, medical care systems, housing, education, and the environment. As Moran said, “Transportation is not a siloed topic.”