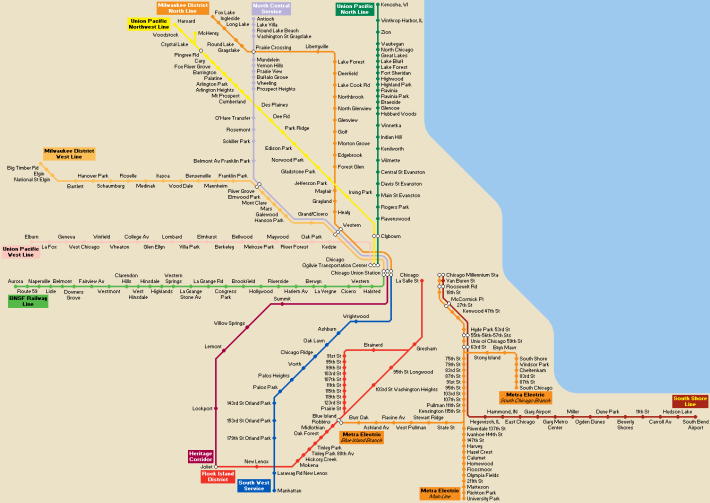

Metra is a transit agency that provides commuter rail service largely geared towards people traveling between the suburbs and downtown Chicago for 9-to-5 jobs. It also offers limited commuter service within the city, as well as some near-rapid service between downtown Chicago and the Hyde Park neighborhood, where the University of Chicago is located.

During the COVID-19 pandemic the number of people working in offices has plummeted. Of people who are still showing up in person for downtown office jobs during the crisis, many are driving rather than taking Metra. In response, Metra is running fewer trains on all lines. In addition, the railroad is currently running the usual Sunday schedules on Saturdays, too, which means some lines have no weekend service.

Ridership in November 2020 was up 24.3 percent compared to October 2020 but down 91.7 percent compared to November 2019. People still made 498,000 trips on Metra in November 2020. The railroad's dependence on people who are currently telecommuting returning to their offices was reflected by a sentence from a recent board meeting slideshow discussing who is and isn't a potential Metra rider: "If their business has not returned to the workplace, they are not a potential customer."

Earlier this month during a presentation for Northwestern University’s Sandhouse Rail Group, Metra CEO Jim Derwinski said he's willing to "try something that I’ll call 'regional rail.'"

Regional rail is the antithesis of commuter rail. While commuter rail serves most stations during traditional rush hours and some stations outside of those periods, regional rail is an all-day network for everyone. (Metra is part of a bigger network in that it's augmented by a few connections with CTA 'L' lines, such as at the Jefferson Park transit center, and in the future that network could be augmented by bus rapid transit connections to travel between suburbs without having to head downtown.)

Regional rail is common in Europe, especially in Paris with its "regional express rail" (RER) network, all major cities in Germany, the entire Netherlands, and Greater London. Closer to home, Toronto's commuter rail agency, GO Transit, is slowly transitioning to regional rail and has already upgraded two of its seven lines to run every half hour instead of hourly (since 2014). Amtrak's Northeast Corridor on the East Coast combined with Metro North and Long Island Rail Road trains exhibit characteristics of regional rail, connecting big cities with smaller cities at all times of the day – connecting five states and focusing on New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. (Although it's likely that this system emerged accidentally, rather than being intentionally designed.)

Regional rail at its most basic means running more trains. The vision is to better connect suburbs to the city, suburbs to suburbs, and even crosstown trips within the city. Rush hour transportation works for people who start work during that time, but it's a bad time to travel for non-work trips (which are the majority of trips we take on a daily basis) because of crowded vehicles. Outside of rush hour, though, transit service is less frequent. When transit is less frequent, getting where you need to go on time requires making connections, which depends on transit vehicles meeting each other at connection points at the right times. Without high frequencies, a missed connection could mean a missed opportunity to learn or work that day.

The Chicagoland regional plan, called ON TO 2050, calls for beefing up transit service across the metro area. "The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning [which created and implements the plan] kept speed, frequency, and reliability in mind when developing transit recommendations," spokeswoman Dawn Raftery said. "Through our research, we have found people who rely on transit the most often do not work traditional '9 to 5' work schedules."

Anne Alt, a Beverly resident who has been commuting via the Rock Island Line to downtown Chicago for 16 years, said a regional rail scheme would be helpful for making connections. "For me, regional rail would mean better connectivity between modes (Metra to Pace, CTA, Amtrak) and off-peak trains that are more frequent than the current two-hour headways that are common on weekends (and weekdays during the pandemic). With some connections, the Metra train arrives 5-10 minutes too late or leaves 5-10 minutes too early for connections to be feasible."

Nearly seven years ago, the Active Transportation Alliance and the Center for Neighborhood Technology revealed their vision for an expanded regional rapid transit network, with support from Cook County President Toni Preckwinkle. The proposal was called Transit Future and called for raising sales taxes in Cook County to fund new and extended bus and rail lines and more service. ATA and CNT spent several years lobbying for the Cook County Board to create a new sales tax revenue stream. The effort was derailed in part by Republican governor Bruce Rauner's failure to pass a normal budget for two years.

One of the great aspects Chicagoland having historic and widespread transit infrastructure is that it's possible to make better use of infrastructure that's already there, rather than having to start from scratch. Regions around the country are spending a lot of money developing new transit ways and building up the land use densities around them to create and sustain ridership. Chicagoland already has the tracks, stations, vehicles, and people living and working near stations.

David Lassen, who reported on Derwinski's speech in Trains magazine, wrote, "Derwinski says he foresees more midday and weekend trains." Between Metra's morning and afternoon rush hour services, most trains sit in yards. What's most costly in an expanded service scenario is paying for fuel and people to operate and maintain the existing trains. Metra would likely need additional funds from the region or the state to start up regional rail service until ridership can grow to sustain more of the costs with fares.

Derwinski defined regional rail like this: "Maybe they’re every half-hour, and during rush hour, every 15 minutes. It lets people know there’s always going to be a train to come — not as fast as rapid transit [like the 'L'], but definitely more enhanced than the one- or two-hour windows we have now."

Metra can start working immediately towards this goal. For example, Derwinski said that the freight railroads that own most of the tracks Metra uses are a barrier, and the relationship with at least one of them is sometimes fraught. The service characteristics that Metra will need to modify to convert to regional rail are too long for this article, but it's worth highlighting one of them because of a change just implemented: Pricing.

Under the Fair Transit South Cook initiative, which launched this month and is subsidized by Cook County, fares on Metra's Rock Island District and Electric District lines are now 50 percent lower for three years to increase ridership. No Metra service changes were made, except that the Electric District has had reduced service since a timetable change in 2018.

Separately, the regional transit agencies must work together on a fare policy for transfers between modes and agencies. Metra is studying fare changes for itself. Ideally, regional rail is part of regional transit in that it doesn't matter how or when someone needs to travel by transit, there is a simple fare and payment method.

Cities can also play a part in developing regional rail: To support transit ridership, new job centers and housing need to be established near transit nodes. Thankfully, it's a mutually beneficial arrangement: Property values are sustained or increased near Metra stations, and property taxes could be used to sustain or increase transit service.

The pandemic has shown flaws in many cities' land use choices of placing so lots of parking near train stations. While the trains are still running, and many people still rely on them, the land around them is empty. Things are slowly starting to change in Metra suburbs like Naperville, where one developer is building more housing near transit.

Alt, the Beverly commuter, noted that a regional rail scheme would have perks beyond work commutes. "The most obvious benefits would be improved opportunities for recreation, casual travel, and tourism, as well as reduced congestion and pollution. If it's easier for local people to visit family and friends by train, to go out for entertainment or recreation, they're less likely to get in their cars. This could be a boost to both Chicago and suburbs, enhance revenues for businesses and tourist destinations, and encourage job growth."

To have a convenient rail network that gets people to where they need to go when they need to go there, the Chicagoland needs leadership on regional transit once again.

Disclosure: Anne Alt works for FK Law Illinois, a Streetsblog Chicago sponsor. Neither Alt nor FK Law Illinois had any influence over the content of this article.