With an already threadbare social safety net stretched beyond capacity during COVID-19, and federal emergency funding running out, the pandemic has become a crucible for an array of longstanding inequities, often scrutinized as independent social ills, to boil together into a crisis. Inadequate access to nutritious food, transportation, healthcare, education, job opportunities and other basic amenities in low-to-moderate-income communities of color—problems that existed well before the coronavirus—have worsened to the point that their cyclical interconnectedness is undeniable.

This week, the Active Transportation Alliance held the third in a series of Zoom town hall meetings around transit justice, this time to discuss the intersection of two basic needs often unmet in Black and Brown communities, and now exacerbated by the pandemic: food security and transit access. Panelists included 3rd District state senator Mattie Hunter, 4th District state representative Delia Ramirez, Hyde Park Food Pantry director Jan Deckenbach, Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago’s Children community programs manager Ruth Rosas, and Cosmos Ray, member of the Bronzeville Kenwood Mutual Aid Network. ATA bus organizing fellow Rylen Clark, who uses they/them pronouns, served as moderator for the event, which discussed the depth of the problem and possible solutions.

After a round of introductions, Clark asked the panelists how food access and transportation policy solutions could be tied together. Ramirez and Hunter talked about how constituents and organizations could work with legislators to implement their ideas, and Hunter listed a number of recently passed agricultural bills.

Ray noted that hunger is an immediate problem, one that can’t wait for the wheels of government to turn. “While I think policy is necessary, what we’re seeing from national statistics is that 15 million more people are food insecure than this time last year,” he said. “I think the Mutual Aid Network is the best at rapid response. The other stat that hurts my feelings is 40 percent of food is wasted in the U.S. There is no shortage of food.”

One challenge faced by the Mutual Aid Network is moving food from parts of town with a surplus to areas in need. Ray suggested imaginative approaches during the crisis, like using CTA 'L' cars and off-duty buses on their way back to the garage to transport food across the city. “We have to re-imagine a new system,” he said. “Trying to ship food 1,500 miles across the country for it to ripen on a shelf, those days are over. We’ve seen how fragile this system is.”

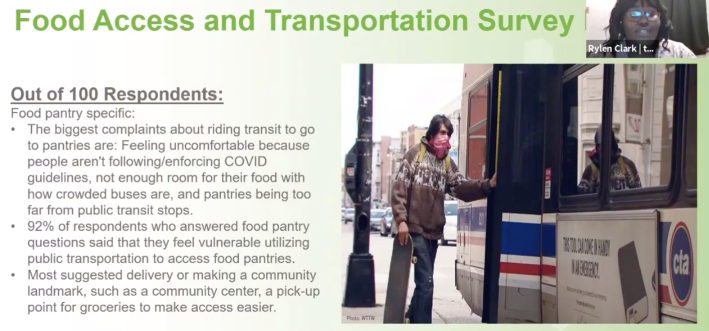

Deckenbach emphasized the importance of public transportation for people coming to the pantry from other parts of the city, some of whom visit her Hyde Park location from as far as Hegewisch. She also suggested creating pop up pantries and food pickup locations in empty storefronts along bus lines and near train stops, specifically mentioning spaces in Grand Boulevard Plaza at Garfield Boulevard and the Dan Ryan Expressway.

Rosas asked how to effectively advocate for transportation funding for transit, walking, and biking. “When funding is cut for transportation more is allocated to highways. Not everyone uses highways, but everyone uses sidewalks,” she said. “The prioritization process is confusing for local residents. How does the state prioritize making sure our transit systems are being funded so they have access to grocery stores or whatever they need?”

Hunter was eager to connect the advocates with her staff and the Illinois Department of Transportation.

ATA campaign manager W. Robert Schultz III mentioned that ATA and other organizations have successfully collaborated with IDOT on several projects, including securing funding and hosting training webinars to help suburban and downstate communities access said funding for walking and biking projects. “The key issue is, we’ve got the money, we’ve got the energy, but not all of our government agencies are sympathetic to the new way of getting around, so we’re trying to break that paradigm,” he said. “We have allies in IDOT who see a sustainable future, but admittedly heretofore it’s been a car-centric agency. It takes a lot of energy to get a shift going in another direction.”

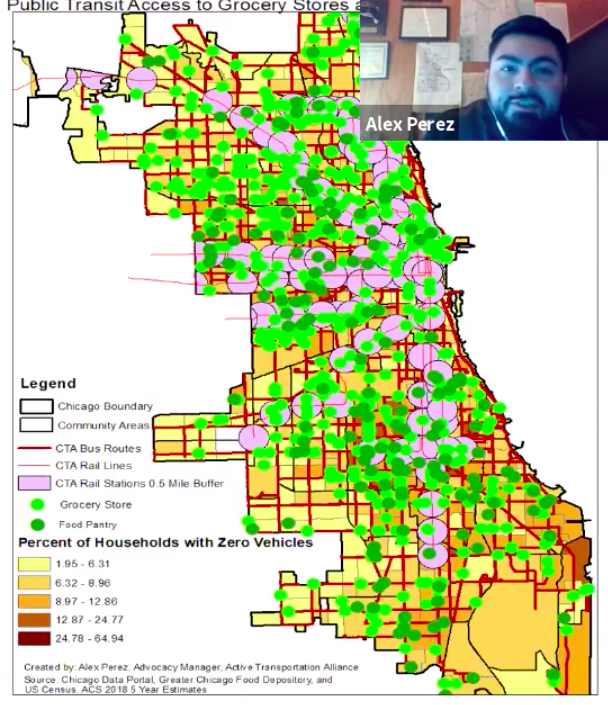

Data presented by ATA advocacy manager Alex Perez presented four maps that highlighted how overlapping inequities overlap compound systemic problems. The first showed the location of grocery stores and food pantries in the city. Then Perez showed the first map with an overlay of CTA train stops and bus lines. The third image was a heat map showing percentages of people without access to a car. And a fourth image overlaid all three data points. The final image revealed areas of the city—notably the southwest and east sides—with concentrations of people without cars who have no grocery stores in their immediate area and no nearby bus or train lines to take to the closest one.

Clark asked the panelists how their organizations could support one another. Deckenbach said that the Greater Chicago Food Depository is providing funding to start new food pantries in areas most in need, and asked for help spreading the word to anyone interested in starting a pantry.

However, Ray expressed reluctance to partner with GCFD. “We focus on solidarity instead of charity. Sometimes if you go to GCFD you might need to show ID or be sober. The barrier to access has been an issue for us,” he said.

Deckenbach also offered to talk through the logistics with anyone interested in opening an independent food pantry.

Ray said the Mutual Aid Network could use additional food and supplies, as well as volunteers able to make deliveries. He also encouraged people to practice mutual aid in their own communities. “Mutual aid starts hyper-locally. Check in with your neighbors and see how they’re doing,” he said.

One of the final questions came from an audience member who asked how food access advocates and public transportation advocates can work together. Ray stated that community members often have answers, but no access to the power structures that can make change. Rosas agreed. “Talking to community members and working with them directly opened my eyes,” she said. “People don’t see food access as separate from health care access and how to get around. When we get too fragmented in or work, we wind up making decisions that aren’t best for our communities.”