In the early 20th Century, Chicago was viewed as a "promised land" for African-Americans fleeing oppression in the South. But while the Great Migration north provided new opportunities, racism continued to be a major issue for Black Chicagoans.

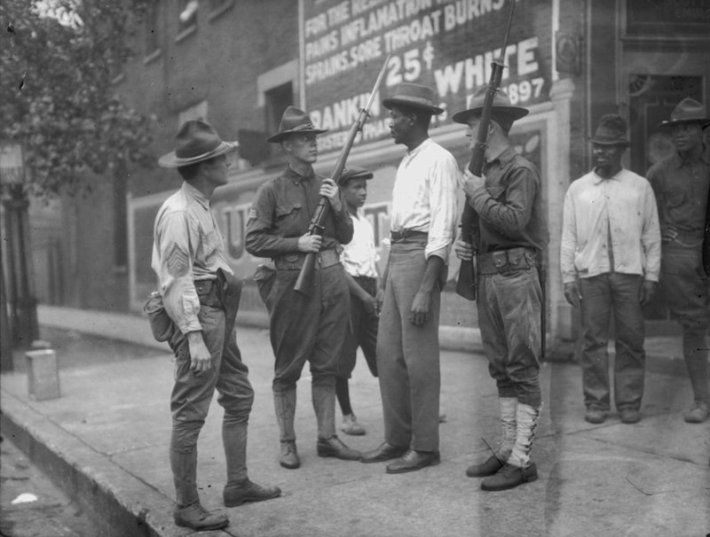

Post-World War I racial tensions came to a head during the Chicago Race Riot of 1919, which took place in Bronzeville and Bridgeport. While it was the most violent such event in Illinois history, with 38 people killed, many local residents aren't familiar with that history

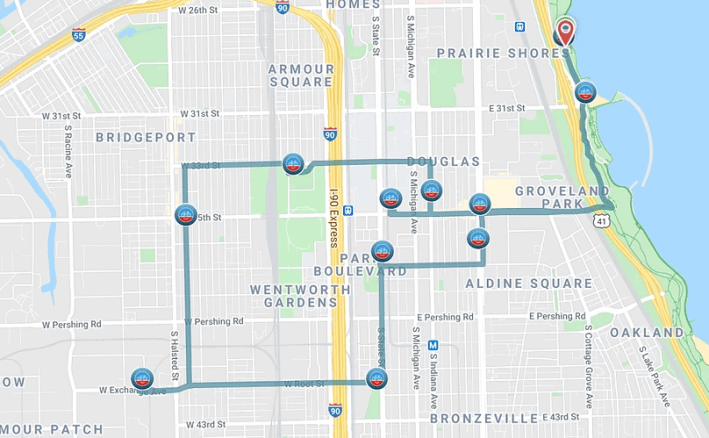

For the 100th anniversary of the riot, Dr. Peter Cole, a history professor at Western Illinois University, and Dr. Franklin Cosey-Gay, project director of the Chicago Center for Youth Violence Prevention at the University of Chicago formed the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project (CRR19.) Last year, partnering with the Newberry Library, they created a bike tour route that visited important historical locations related to the riot and partnered with the Woodlawn-based bike education center Blackstone Bicycle Works to lead a ride where speakers told stories about the events of 1919 at each stop.

Cole told Streetsblog that the bike ride seemed like a good way to spotlight "the origin story of racism in Chicago." He noted that this history is particularly relevant in a year that has seen widespread civil unrest in response to the killings of unarmed Black people by police.

"The term 'race riot' has changed over time," Cole said. In the late 20th Century it became associated with Black uprisings as a reaction to injustices. But prior to the sixties, Cole explained, "that term meant white mobs killing Black people. It's not a simple conversation or a short conversation, but that term means different things to different people. I'm very aware that very few people in the suburbs and downstate know about it."

Cole said the idea for the bike tour materialized "a couple of years ago, after spending time in Berlin, where there is a lot of memory over the Holocaust." Germany has confronted the horrific events of World War II and made an effort to ensure that these atrocities are never forgotten. "The contrast is striking between what Germany has done and what America has not done."

In 1919 African Americans made up only four percent of Chicago's population. Despite this, there was quite a bit of hostility and violence towards Black Chicagoans from whites. Cole cited "more than two dozen bombings of Black people's homes prior to the riot, essentially what we would now call white terrorism."

Unfortunately, that was only the beginning. "The spark [for the riot] was when five Black kids went swimming on a very hot Sunday afternoon," Cole said. "There was only one beach that tolerated Black people, at 25th Street. When these kids went swimming, they made a raft, and they drifted a little southward towards what now is 29th Street. Basically a white guy started throwing rocks at these children when they crossed an invisible line in Lake Michigan that indicated this was a 'white part of the lake.' One of these kids drowned -- Eugene Williams, age 17."

When Black residents asked the police to take action, responding officers would not arrest the white man, instead arresting a Black man. "That night gangs of white men from Bridgeport headed east down 35th Street into what is now essentially where IIT is located," Cole said. Random black people were attacked for a week, with 38 people killed, 23 of them African-American, and 537 injured.

During the last year's bike tour, which took place in July, 40 people pedaled around Bronzeville and Bridgeport. "The area where the rioting occurred across is pretty large," Cole said. "Although it's possible to walk it, it would take many, many hours, and not everyone would be into that. Going around by car, if you go too fast [you miss details], and you have to stop and park. Bicycles are really the ideal mode of transport to cover ground slow enough that you can see things, and stop easily and quickly, and fast enough that you can cover ten square miles." This year, for the 101st anniversary, there were 175 cyclists along for the masked, socially-distanced ride on July 25. Cole cites the Black Lives Matter protests as a possible reason for the large turnout.

If you're interested in riding the route, it's possible to do the ride independently. Better still, if you complete the course by October 31, you could help Blackstone Bicycle Works receive a grant to support its important work with youth from low-income communities. The bike parts and accessories companies SRAM and ABUS will $7500 if 300 people do the ride by Halloween, with a portion of the money helping to fund CRR1919’s project to install 38 markers at the sites where people were killed during the riot.

Riders can follow the route by downloading the mobile app Ride Spot, a platform developed by the national advocacy group People for Bikes, and joining the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Route challenge. Riders will be guided by turn-by-turn directions to each stop along the route. They can also download or stream an audio tour or but a 1919 CRR Route Guidebook.

To learn more about the 1919 Chicago Race Riot and how to do the bike tour, visit crr1919ride.com.