Thanks to Streetsblog writers James Porter and David Zegeye for providing input for this piece.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many U.S. cities have been banning or restricting car traffic from streets to open them up for safe, socially-distanced pedestrian activity and biking. In particular, Oakland, California's "Slow Streets" program, which has prohibited through traffic on 74 miles of side streets all over the city, at low cost and with no additional policing, seems promising. However, there has been some pushback against the calls for open streets from Black and Brown mobility justice advocates in various parts of the country.

I understand the criticism given the very real concerns about distribution of city resources, policing, and community engagement. There's also the fact that African-America and Latinx neighborhoods are disproportionately impacted by healthcare disparities, unemployment, and housing insecurity during the pandemic, as well as the high incidence of COVID-19 deaths in the Black community.

Here in Chicago, Saturday's demolition of a 95-year-old industrial smokestack on the Southwest Side sent a huge cloud of irritating dust into nearby POC neighborhoods, creating a new source of fear during in the midst of a respiratory pandemic. Air quality in this part of town is further compromised by heavy diesel truck traffic that continues during the crisis. These factors contribute to unhealthy conditions for walking and biking.

Recreation is a privilege at this time. I'm reminded of this quote from a recent TreeHugger article discussing some of the ways urban design will be impacted by COVID-19.

The virus has exposed a deep density divide: rich people density, where the advantaged can do remote work and order in delivery from their expensive homes, versus poor people density where the less advantaged are crammed together in multigenerational households who must head out on transit to work in crowded, exposed conditions. This density divide weakens all of us because vulnerable communities open all of us to the spread of the virus. A city cannot be safe if it is not equitable.

It bears repeating that Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in America. An outcome of segregation is inequality: There are large disparities between Black and Brown Chicagoans and white Chicagoans when it comes to educational attainment, income, health outcomes, and commute length, to name a few metrics. It's no surprise that there would be a divide when it comes to opinions on how the city should respond to COVID-19.

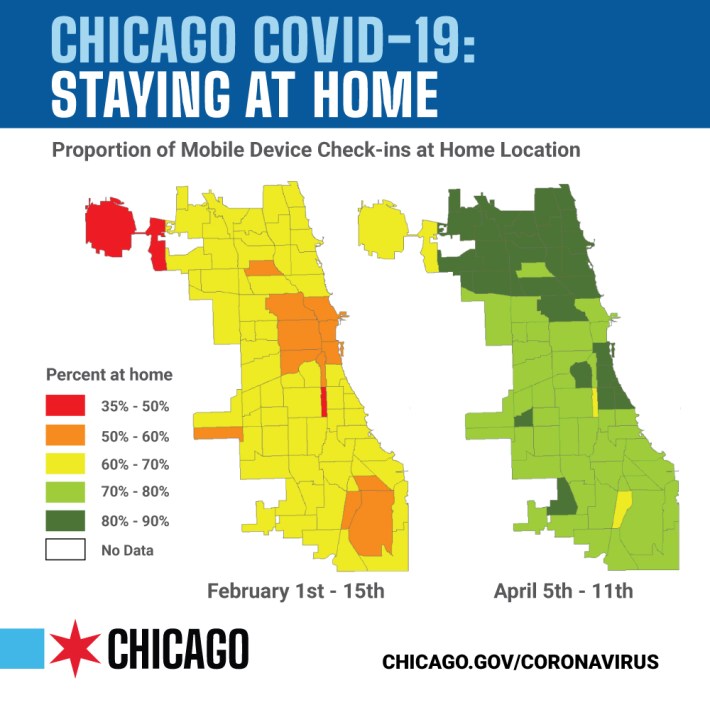

Many Chicagoans calling for car-free or car-restricted streets during the pandemic live in North Side neighborhoods that are majority-white and largely middle to upper income, with many residents working from home during the pandemic. These areas includes some of the city's densest pedestrian-oriented communities, where lack of space on sidewalks for social distancing is more likely to be an issue. These neighborhoods also have high levels of biking.

On the South Side, which is majority Black and Latinx, residents are grappling with the aforementioned pandemic-related , healthcare disparities, unemployment, housing insecurity, higher mortality rates, and industrial pollution, as well as the ongoing issue of heavy police surveillance and harassment. They're more likely to work essential jobs that require showing up in person. These parts of town are also generally less dense and more car-oriented. For all these reasons, open streets is less likely to be a pressing concern for South and West siders.

I hate thinking in terms of binaries. North Side residents are not wrong in calling for open streets, nor are mobility justice advocates who live on the South and West sides wrong for arguing that that open streets is not a priority in their neighborhoods. I realized early on that different communities have different needs, which is why I proposed allowing people who truly saw a need for open streets treatments in their neighborhoods to request them from the city.

Both sides are responding to their lived experience. Folks on the North Side who are going out for a walk or a bike ride to make an essential trip or take a break from being cooped up at home are at risk of being hit by drivers. Many of them have tweeted about their encounters with reckless motorists. Crowding on sidewalks, which doesn't allow for social distancing without stepping onto the parkway or into the street, is a very real thing in the dense, racially and economically diverse Rogers Park neighborhood on the Far North Side, where I live. Even though some folks are brave enough to walk or run in the street, they're being passed by drivers who are often going too fast for conditions.

Just as real are the experiences of South Siders who have experienced dangerous crowding on CTA buses during the pandemic as they make their way to essential jobs. (Recently the CTA began addressing this issue with de-crowding measures, like allowing bus drivers to run express after they reach a certain capacity.) And people in POC communities often experience police harassment just for existing outside their homes. All of the above issues must be addressed.

Some op-eds have pointed out that COVID-19 has shown us yet another way that America is failing its most vulnerable. I agree. The crisis is a chance to rethink business, healthcare, income inequality, workers' rights, policing, and the prison system. This period when driving has plummeted and walk/bike has surged is also a unique opportunity to take a fresh look transportation and land use, and their impact on public and environmental health.

I agree with Untokening members that broad, permanent changes to our transportation networks should not be happening when community engagement is difficult. Many people have much more pressing issues on their minds, and not everyone has access to the Internet to weigh in on proposed initiatives. However, I don't see any harm in temporarily creating more space for people to safely travel and recreate, especially if Chicago modeled its efforts after Oakland.

Oakland’s Department of Transportation had equity in mind when dedicating 74 miles of neighborhood streets for bikes, pedestrians, wheelchair users, and local vehicles only. In a section on the city of Oakland's Slow Streets webpage titled “COVID-19 Exacerbates Inequalities," Oakland DOT acknowledges that some parts of the city have inequitable access to parks and open space, and low wage income earners and single parents are less likely to work jobs that allow them to telecommute and have childcare options. “OakDOT seeks to reduce barriers to opportunities for physical activity and ensure safe transportation for our most vulnerable community members,” it states.

Imagine the transformation we could make if more city officials recognized inequalities and worked to reduce them with significant input from residents. I'd love to see city departments prioritize fighting inequalities and climate change, and work with residents to improve outcomes for humans, animals, and plant life.

The divide between white and POC perspectives is a longstanding problem that impacts many aspects of our society, including transportation. It's unfortunate that ignorance regarding the lived experiences of Black and Brown people continues. It would be helpful for more Chicago sustainable transportation advocates to educate themselves about the issues affecting African-American and Latinx communities.

If you're interested in learning more about how to center the experiences of BIPOC (Black and Indigenous people of color), women, and trans folks when it comes to mobility issues, you may be interested in getting involved with the Cyclista Zine community. Cyclista was created “to shed light on lack of inclusion of underrepresented communities in cycling and to disrupt cycling media outlets and mainstream narratives of who cycles.” They regularly share articles and other content that includes or centers the perspective of Black and Brown people in a mobility justice context.

Here are some tips on preventing the spread of COVID-19, and advice for Chicagoans on what to do if you think you may have been exposed to the virus.