Earlier this month the Illinois Department of Transportation hosted the tenth North Lake Shore Drive Task Force meeting on the project to reconstruct Chicago's iconic, but excessively wide and car-centric, shoreline highway. It was several months after the last such meeting took place last July.

The March event focused on the possibility of converting two of the drive's eight travel lanes to managed lanes. These would give drivers the option of paying a toll to use the theoretically less-congested right-of-way, with the cost of the toll rising as more drivers enter the lanes, i.e. congestion pricing. CTA buses would also be also use these lanes. However, the Active Transportation Alliance has noted that it's possible that the managed lanes would still fill up with cars, and it would be politically difficult to keep raising the tolls, so dedicated transit lanes are needed.

Unfortunately, the possibility of adding light rail to the drive is no longer on the table. But thankfully things like transit-friendly stoplights, queue jump lanes (which give buses a head-start over other vehicles), and converting mixed-traffic lanes to bus-only lanes are still in the mix.

During the meeting, officials discussed five scenarios for accommodating buses. The different options were projected to cut an average of 5 to 20 minutes over existing transit trip times.

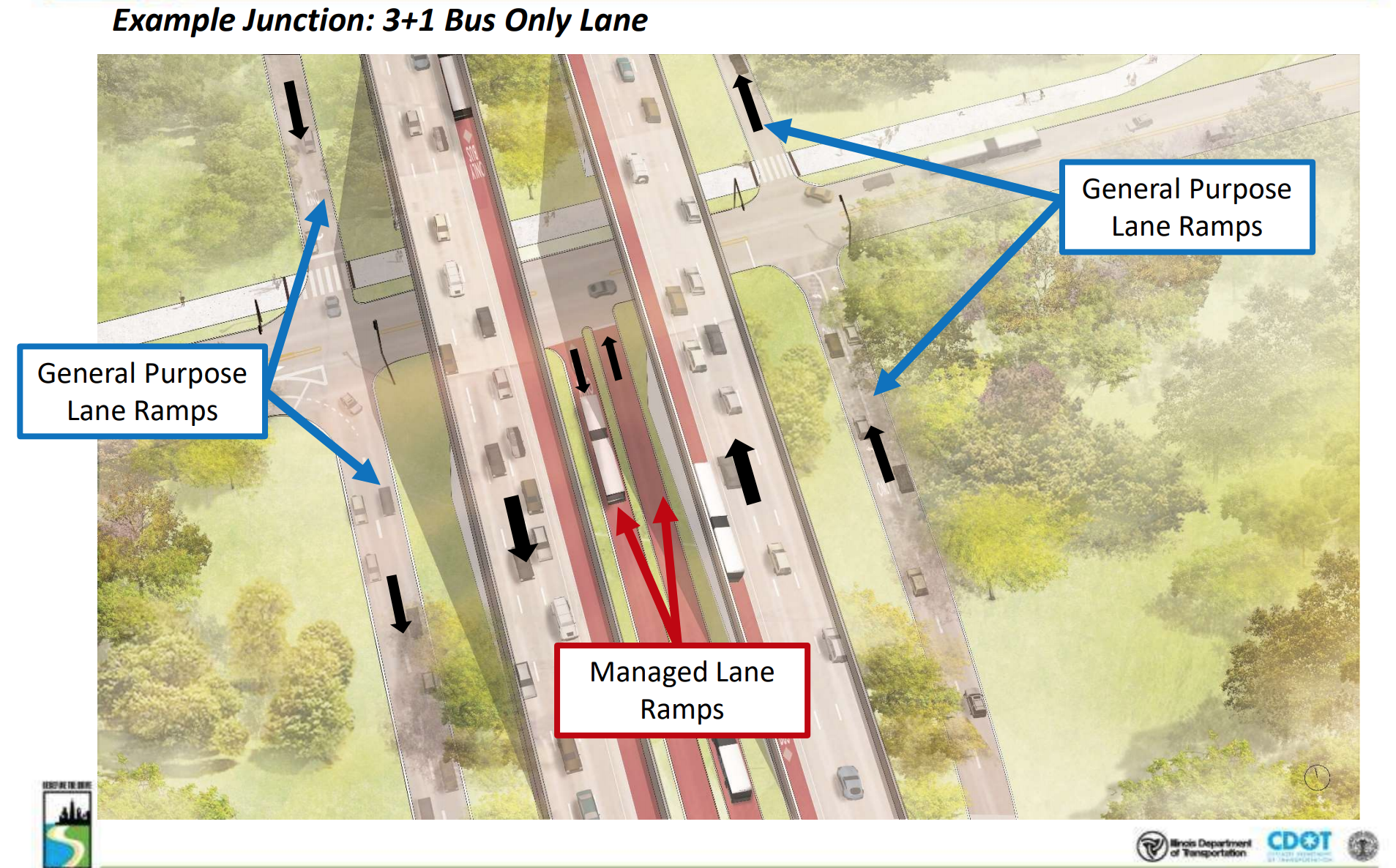

The strongest of the five possible layouts is the 3+1 Bus Only Lane scenario. The main drawback of this scheme, which would have the buses in the center lanes, is that there could be complications for downtown service, and in the event that the busway is eventually upgraded to rail. Interestingly, the CTA rep present at the meeting mentioned that a potential bus network redesign was in the works, with the express buses getting special attention, so this strategy could be in flux.

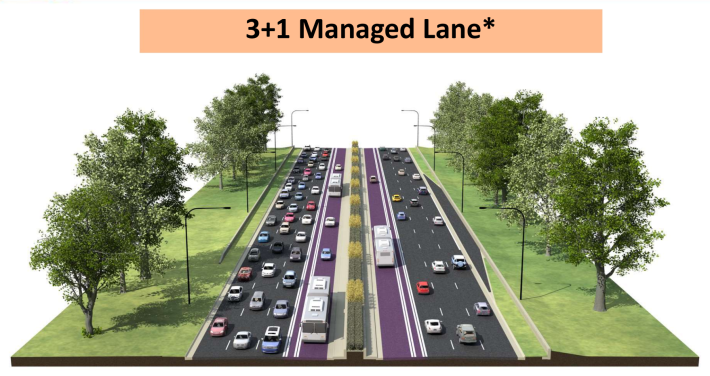

Then there's the three more car-centric managed-lane scenarios, 3+1 Managed Lane, 2+2 Managed Lanes, and 3+2 Reversible Managed Lanes. 3+1 is identical to the Bus Only Lane layout, with the main difference being that a limited number of toll-paying drivers would mingle with the buses. That could could be easily converted into Bus Only Lane or even light rail in the future.

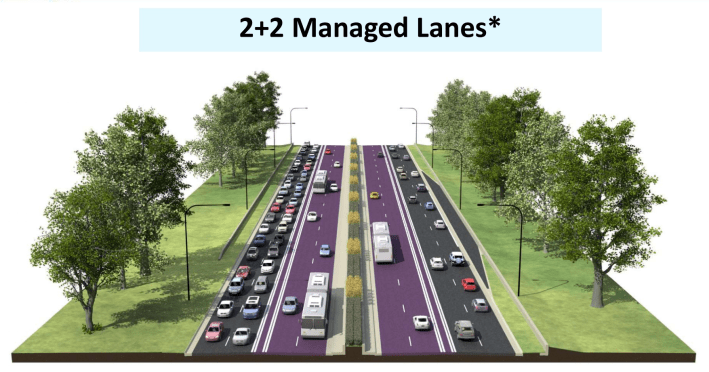

The 2+2 scheme has the same devotes two lanes in each direction to managed lanes shared by tolled drivers and buses.

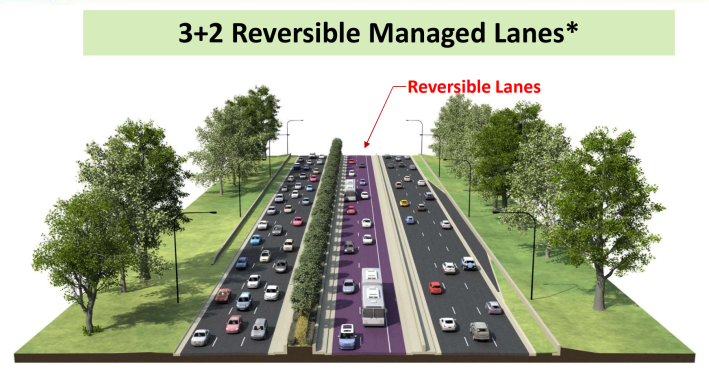

The 3+2 Reversible layout, would have reversed the flow of traffic in two central managed depending on the time of day. That idea was ultimately scrapped, but it was an interesting proposal with a similar scenario to the I-90/94 express lanes.

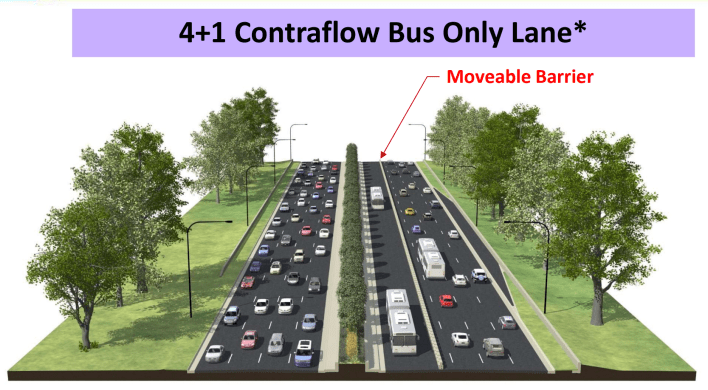

The last scheme, 4+1 Contraflow Bus Only Lane, is a bit of an oddity. In this layout, a moveable barrier would be used to create one inbound bus-only lane during the morning commute, while maintaining four lanes for inbound drivers, leaving three lanes for buses and drivers doing the outbound reverse commute. The barrier would be removed at all other times of day, reverting to the current layout.

While these sort of movable lanes are common on things like bridges, such as the Bay Area's Golden Gate Bridge, few have been attempted on this scale. In addition, the barriers could impede the movements of emergency vehicles that frequently use North LSD to bypass busy local streets.

While these sort of movable lanes have been used in Chicago on South LSD and are common on things like structures like the Golden Gate Bridge, the longest, at 13.8 miles, is on I-30 in Dallas. While North LSD is much shorter at 6.4 miles it is also much narrower and without proper shoulders, meaning this strategy may require widening the road at strategic points, or else the barriers could impede the emergency vehicles that frequently use the highway to bypass busy local streets.

One problem with most of these scenarios is that there would be little or nothing in the way of physical barriers preventing drivers from entering and exiting the bus-only or managed lanes. Currently Illinois law does not allow for camera enforcement of bus lanes, although Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot has said she plans to lobby for such legislation to make busways on surface streets more effective.

Then there's the difficult decision of how to actually toll the drivers. There's also the question of whether existing or future legislation could even support such a change.

Near the end of the meeting, IDOT officials shared projections about how much car traffic would be added to surface streets under the different scenarios. Only the 3 +1 Bus Only Lane scheme was predicted to push a significant amount of drivers off the drive and onto local roads. Of course, if you take space away from drivers on Lake Shore Drive and make buses much faster and more reliable, it's likely that a significant number of existing car trips will be replaced by by transit rides.

During the Q&A session, an attendee voiced concern about what they called a lack of transparency in how IDOT reached its data conclusions, particularly in regards to mode shift. When asked about the predicted shift in drivers from Lake Shore Drive proper to the Inner Drive, IDOT argued that this would be bad for transit riders because an increase in traffic on local streets would hamper buses on the Inner Drive.

You can let IDOT you support adding bus-only lanes to North Lake Shore Drive by providing input on the project website. You can also email email info@northlakeshoredrive.org.

View the presentation and materials from the March task force meeting here.

Here are some tips on preventing the spread of COVID-19, and advice for Chicagoans on what to do if you think you may have been exposed to the virus.