Earlier this month NBA great LeBron James announced a Lyft program called LyftUp, which will provide free one-year bike-share memberships for low-income young people between ages 16 and 20, starting with New York's Citi Bike program and soon expanding to include Chicago’s Divvy system and the Bay Area’s BayWheels network. In his announcement, James also stressed the importance of cities building safe bikeways to protect children and other residents.

In his announcement, James said, “A bike opened doors, allowed me to get to safe places after school, and gave me access to opportunities I never would have known.” Lyft’s co-founder and president John Zimmer shares his goal for the program, “With LeBron as our inspiration, we want to demonstrate how transportation can be a spark that helps young people reach their full potential.”

It’s a very laudable vision, and when I heard about LyftUp, I was happy that happy more teens would be gaining access to bike-share. However, an Instagram post about the initiative from Cyclista Zine, a cycling advocacy zine focused focused on "sharing knowledge and the stories" of BIPOC (Black and Indigenous people of color) and FTW (femme, trans, women) people in cycling, was thought-provoking.

The post included a quote from former Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition executive director Tamika Butler, a very visible Black and queer presence in the bike advocacy world. (Scroll up on the sidebar of the Instagram post to read the quote.) Butler stated, “There is debate on whether or not these changes [venture capital and tech companies joining the bike-share field] are good or bad, and there are questions about whether private companies are getting involved because they care about transportation and mobility solutions, or because they want to gain data and market share. When decisions about access to mobility are made based on profits, can we achieve the outcomes we promised about equity with public bike share systems?”

In addition to questions about for-profit companies running transportation systems (the city of Chicago owns the Divvy system and has a contract with Lyft to operate the network), there's the issue of the negative impact ride-hail companies like Lyft have on traffic safety, including bicycle safety. If you ride a bike for transportation in a city like Chicago, you've probably encountered ride-hail vehicles parked in painted bike lanes, heard stories from fellow cyclists about a Lyft or Uber driver who put their safety at risk in some other way, or had a run-in with a ride-hail driver yourself.

A University of Chicago study estimates that, due to increasing the amount of driving in cities, Lyft and Uber have increased traffic deaths by 2-3 percent nationally. While Lyft claims that their drivers are not employees, the company should still take some level of responsibility for ensuring that drivers who use their app for income are not a risk to people on bike or on foot. Are you really helping young people use bikes to "reach their full potential" through biking when the bread-and-butter of your company, ride-hail, makes streets less safe for cycling, and increases congestion and air pollution?

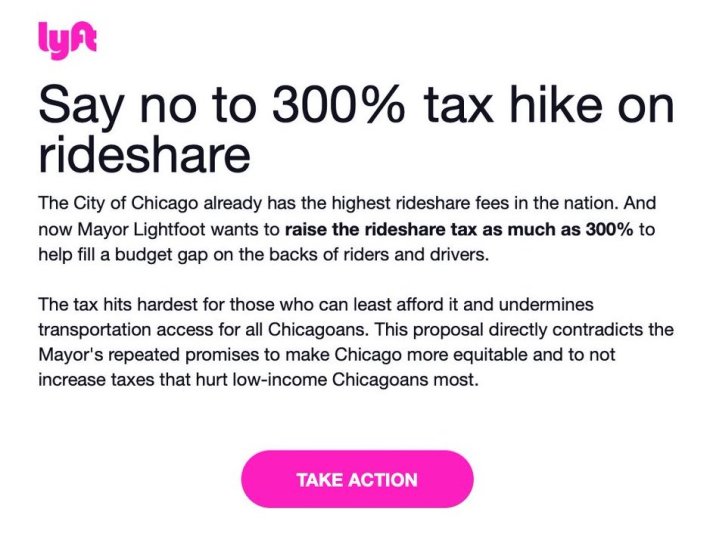

It's also worth noting that this fall Lyft actively campaigned against the city of Chicago's new ride-hail tax structure that passed in November, designed to reduce downtown congestion by discouraging unnecessary and solo trips, address the city's budget gap, and fund CTA bus improvements. The company argued that the fees would hurt low-income residents, but transportation advocates of color pointed out that most trips hailed on the South and West sides, which are the less-expensive shared trips, would actually be a bit cheaper under the plan, and low-income Chicagoans would benefit from improved bus service.

In fairness to Lyft, the company has made some efforts to improve safety, like educating drivers and passengers about the "Dutch Reach" anti-dooring technique. In San Francisco Lyft geofenced Valencia Street, a busy corridor that had seen an increase in injuries to people on bike due to doorings and other collisions.

In my view, cities are partly to blame for crappy street designs that put people on bike and foot at risk from drivers. If a motorist can easily drive or park in bike lane, it’s not a truly safe facility. Still, ride-hail companies should step up to continuously educate their workers about actively watching out for people on bikes and driving safely around them. While safer ride-hail drivers would be an improvement, having fewer Lyft and Uber vehicles on the streets would be even better. When there are fewer cars on the roads, walking and biking become safer, and buses can operate more efficiently.

Beyond ensuring people in disinvested neighborhoods have access to bike-share, we also have to make sure that everyone has access to a network of safe bikeways. While I agree with Streetsblog's Lynda Lopez that infrastructure alone isn't enough to get more Black and Brown people on bikes, building more safe, physically protected bike lanes on the South and West sides is a step in the right direction.

Per Ms. Butler's comments, it's fortunate that Chicago owns its bike-share system and Lyft is simply the concessionaire, rather than having the final say on policy and strategy. It was a reminder of the downsides of privately-owned bike-share when LimeBike recently pulled its privately-owned fleets from Seattle and Boston, leaving residents with fewer transportation options. So while Lyft's latest initiative to provide free bike-share memberships to low-income teens is commendable, we can't ignore the larger negative impacts of ride-hail companies, and the fact that their decisions are generally guided by profit-seeking, not altruism.