Decades ago, before most communications were digitized, and you could get whatever you wanted on demand with the touch of a smartphone, if you needed to send documents or packages across a city's central business district quickly, the most efficient way to do that was by bike courier. While "paper messengers," who carry envelopes and mailing tubes, still exist, nowadays most Chicago delivery bikers transport food.

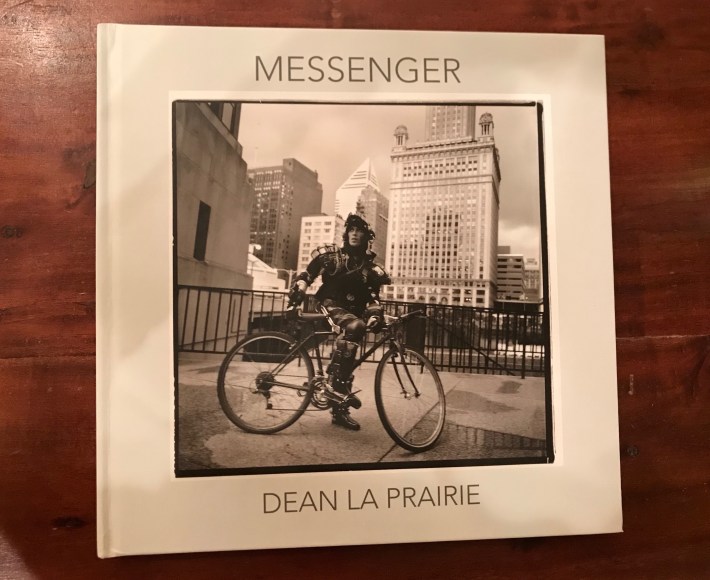

But "Messenger," the photo exhibit by my old Nineties Chicago courier colleague Dean La Prairie, currently showing at URI-EICHEN gallery in Pilsen, offers a window to that bygone era. And during the the packed opening party for the show earlier this month, Ashley Baber, a Loyola PhD candidate in sociology discussed "The Gig Economy Then and Now," looking at the labor issues than affected old-school messengers, as well as modern delivery and ride-hail workers.

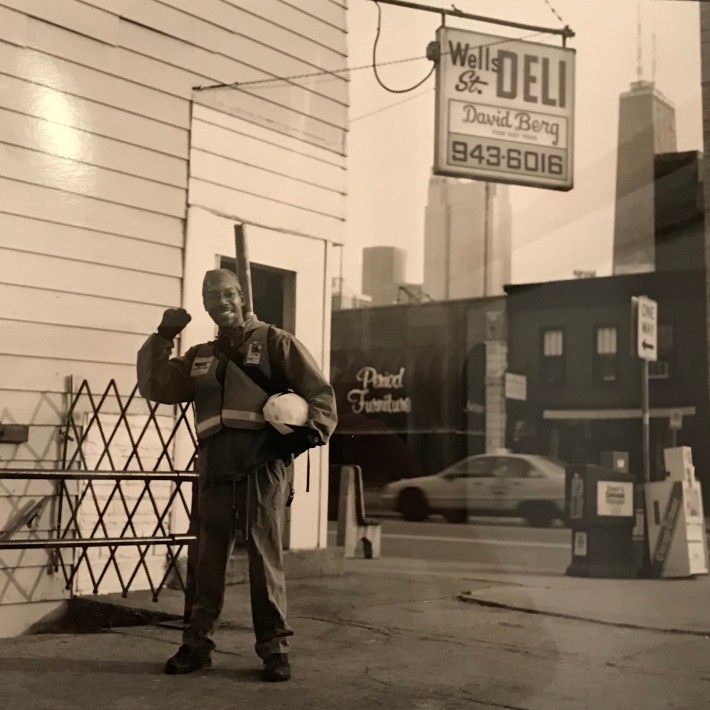

La Prairie shot the black-and-white images images from 1993-95 while working as a courier himself. It was a time when, he said in his artist statement, "the bike messenger was a common everyday fixture of the urban experience, a flesh-and-blood system of communication in a pre-Internet world." While cycle couriers are associated with constant motion, he chose to shoot still portrait photos in a square format "because of its contrast in presenting fluid energy in repose, as well as the square’s challenge of presenting the messenger’s natural environment; the urban landscape."

"The messenger would cover hundreds of miles a week of city streets and make continual incursions in and out of countless office buildings," La Prairie wrote, "to the point that after a measure of time they both became as familiar an environment as their own personal spaces." One of the rewarding aspects of the viewing the exhibit, in addition to seeing what bike couriers looked like and rode 25-plus years ago, is checking out how Chicago's built environment appeared back then, including classic architecture that is largely unchanged today, but also humbler features, including parking garages, hot dog stands, liquor stores, old signs, stoops, bridges, 'L' tracks, and more.

"These photos were never set up," La Prairie said at the opening. "I was working, and it would take a long time for the perfect synergy to happen, like 'Hey, do you have two minutes?' 'OK, I've got two minutes.' And I would shoot them very quickly." In a few cases, getting a still portrait wasn't even an option, because the photo subject would be called away on a run, and La Prairie had to snap their image as they sped away towards a package pickup.

After a screening of the excellent early-Nineties Chicago courier documentary short "Concrete Rodeo," directed by Chip Williams, Baber discussed her research on the gig economy, which focuses on how New York City, Austin, and Chicago have been regulating the industry. She said that gig work is typically defined by what it is not: rather than being traditional, full-time work, it's labor that is done on-demand, job-by-job, or short-term. In addition to traditional bike messengering, this includes activities like driving for Uber or Lyft, freelance writing, contracted construction work, or work acquired through a temp agency. Recent estimates of how many U.S. residents are doing this kind of labor range from as low as 16 percent of the labor force to as high as a third.

This kind of flexible labor is promoted as offering workers low barriers to entry, autonomy over their hours and schedules, the ability to earn "extra" cash, and the opportunity to advance to full-time employment. In reality, Baber said, low levels of autonomy are reported by gig workers, such jobs are increasingly needed to support a low-wage labor market, flexible workers waste a fair amount of time waiting for work, and these jobs rarely turn into permanent employment.

Baber showed a vintage ad to recruit "Kelly Girl" temporary office workers, offering women the opportunity to "turn extra time into extra money," and compared that to a contemporary Uber ad showing a man spending time with a young relative, promising that you can "drive when you want, earn what you need." These rose-colored depictions of the gig economy are sometimes accurate, she said, with some workers reporting that they're satisfied with their status. But others report having to work long hours to make ends meet, and say that changing pay structures are a major problem, particularly for ride-hail drivers.

Historically, using temporary labor was a strategy for companies to avoid providing employees with health care, paid leave, or worker's comp. Similarly, today gig economy businesses, particularly Uber and Lyft, have argued that their workers are independent contractors rather than employees, and therefore aren't entitled to benefits.

Gig workers across the country have been organizing to fight this "misclassification," Baber said, and there have been some wins, such as California's AB5 bill, which classifies ride-hail drivers as employees, and a minimum wage ordinance and cap on the number of ride-hail drivers in NYC. "But Uber, Lyft, and Postmates [which uses bike couriers] are really leading the fight against regulations, and therefore against workers."

Baber argued that, compared to peer cities, Chicago has been "quite welcoming" to gig economy companies. She seemed to take a dim view of our city's new ride-hail tax that kicked in on January 6 in an effort to fight congestion, plug Chicago's budget gap, and fund the CTA, noting that the tax is paid by customers. "It isn't a tax on Uber and Lyft themselves, and of course the drivers don't see any of that money." She added that Uber is expanding its freight sector into Chicago's old main post office, and they're piloting their UberWorks app for temporary work here, which appears to be geared towards at the restaurant industry.

"So cities can make decisions in the interest of workers, or they can make decisions that increase labor market precarity and inequality," Baber concluded.

The closing party for "Messenger" takes place on Friday, February 7, 7-9 p.m. at URI-EICHEN Gallery, 2101 S Halsted. La Prairie will discuss the show at 7:30 followed by a screening of "Concrete Rodeo." The gallery is also open by appointment through February 7. For an appointment call (312) 852-7717.