The Lincoln Yards mega-development is nearly a done deal after a vote yesterday by City Council's Zoning Committee, which approved the $6 billion development on 55 acres of land along the North Branch of the Chicago River. Developer Sterling Bay is counting on a $900 million tax-increment financing subsidy, which will go before the city's Finance Committee for approval on Monday, after which it would go before the full Council for a final vote on Wednesday, March 13.

In light of this news, it's especially important to take a look at the potential impacts of Lincoln Yards on Chicago's transportation network. Last month Jacob Peters analyzed the issue as part of a series on Lincoln Yards he wrote for Chicago Cityscape, Streetsblog Chicago cofounder Steven Vance's development-tracking website, syndicated here with permission from Jacob and Steven.

Note that some of the stats about Lincoln Yards mentioned in this article may have changed somewhat since the latest plans reduced the height of the tallest buildings from 800 to 600 feet and capped the total size of new buildings at 14.5 million square feet. -JG

The Lincoln Yards proposal is a major redevelopment of industrial land that had few workers on such a large site, relatively little car traffic, and nobody living nearby. That will all change as 6,000 new residences and tens of thousands of new jobs are planned to land on the site and nearby. The issue is that there isn’t enough transportation infrastructure to get them there.

My previous article identified small areas in Chicago that have a similar density, of both residents and jobs, to the Lincoln Yards and the surrounding area. We showed that the proposal isn’t that dense, and that much of Chicago’s North Side was denser.

Needs more transit

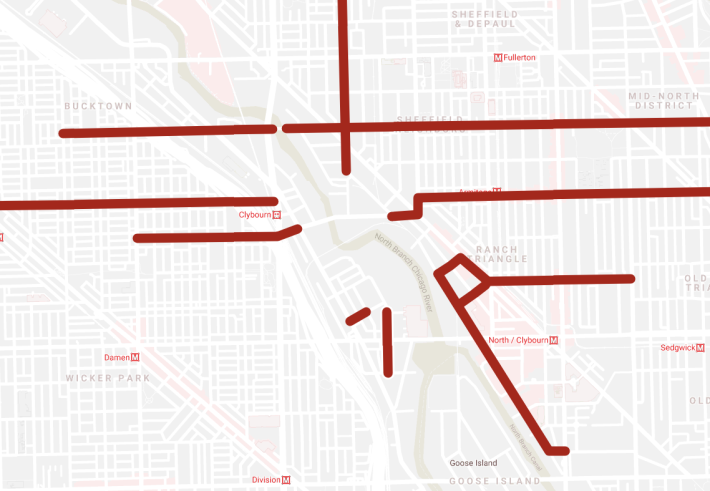

A big difference, however, is that every one of those comparison areas has more transit service than currently serves the Lincoln Yards and surrounding area. (Our “study area” is bounded by Webster, Clybourn, North, and the Kennedy Expressway.)

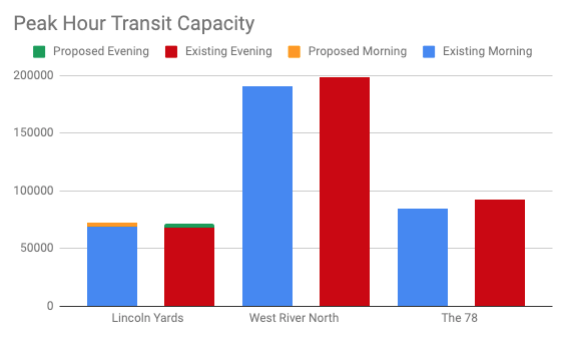

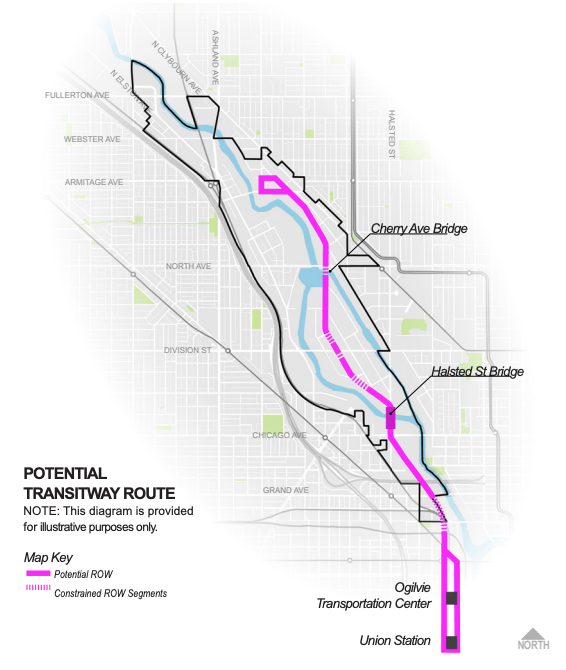

Those comparable areas also have more transit service than the study area will have even if a proposed new transitway ends up carrying as many passengers as the Orange Line BRT in Los Angeles, the highest-performing bus transitway in the United States [1]. The proposed water taxi stops and the transitway are both downtown-centric, and will not measurably improve access to the site from a majority of the city in a way similar to the Loop-adjacent areas identified in the last article.

Transit nerds should also open and read the footnotes. There is a much larger discussion about specific transit alternatives and routes that could be created to integrate the Lincoln Yards and environs into the CTA ‘L’ network.

If investments were made to increase the amount of service from across the region to the Lincoln Yards site, it would lessen the impact of housing cost increases on the surrounding neighborhoods [2], while simultaneously bringing residents closer to new amenities.

The size or scope of a development in a low-density area adjacent to higher density areas only becomes problematic when the transportation infrastructure improvements don’t match the scale of development that is being proposed.

An earlier version of the Lincoln Yards proposal placed a stadium on the south half of the development, to which the Chicago Department of Transportation and 2nd Ward alderman Brian Hopkins ascribed much of the traffic demand.

Now that the stadium has been eliminated, however, the peak demand for transportation to and from the site doesn’t change by much. Why? The stadium’s area was replaced with 1,500 more residences [3]. What changed is how and when people make trips into and out of Lincoln Yards. The additional units could encourage more car ownership — and thus more traffic — among Lincoln Yards residents, since the 6,158 proposed parking spaces will more than double the garage parking within 1/4 mile of the study area [4].

Having an easy place to store a car overnight discourages a commuter from using a bus — especially when the only bus improvements being made are to and from downtown and not to any other job centers.

All that parking on the site could create an awful situation: One commuter drives out of the garage in the morning to get to work elsewhere, while another commute drives into the garage in the morning to work at Lincoln Yards [5]. While it’s great for the garage operator to have a full garage 24 hours a day, it's bad for the environment, shoppers, walkers, and bicyclists.

These commute patterns will make the entire development more car dependent, especially since the number of vehicular crossings of the river in the area will be quadrupling.

More roads = more traffic

Hopkins and other officials have claimed that the new bridges and new streets (creating a new increase in road capacity) will “reduce congestion.” This is simply false due to the fundamental law of traffic congestion, that any new road capacity will be filled with equivalent car capacity within a few years.

These new river crossings will have an indirect on a far wider area than if no new road capacity was being added and the developer and their new tenants aggressively shifted as many new trips as possible to public transit. Privately-operated shuttle buses with infrequent, low capacity service, used only by office workers during rush hour, would not be a viable solution to the transportation needs of Lincoln Yards. The only scenario in which this new network of vehicular river crossings would not increase the congestion that neighbors are complaining about would be if officials address the morphing travel demands of the city in a holistic manner that is heavily bike- and transit- focused.

Supporting a shift to sustainable modes of transportation will require improvements that are done in phases that match the increasing demands created by the upcoming phases of industrial redevelopment. It cannot focus solely on the North Branch Corridor, solely on trips to and from downtown, or solely on improvements to one mode of travel.

Fortunately, the Lincoln Yards “Planned Development” document requires Sterling Bay to conduct new traffic studies and design a set of new transportation improvements be approved by the Chicago Department of Transportation before any subsequent phase is completed [6].

Chicagoans need to be the ones pushing to make sure that those phases of improvements are not primarily car-centric, and that they contribute to citywide public transit connectivity and capacity increases.

Think beyond the transitway

The Active Transportation Alliance has already taken the first step, but we need a comprehensive plan that resolves deficiencies in CTA’s network of bus and ‘L’ routes. District plans like the North Branch Framework Plan and the Central Area Plan are necessary, but they don’t knit together regional solutions to the shifting commute patterns that they help facilitate [7].

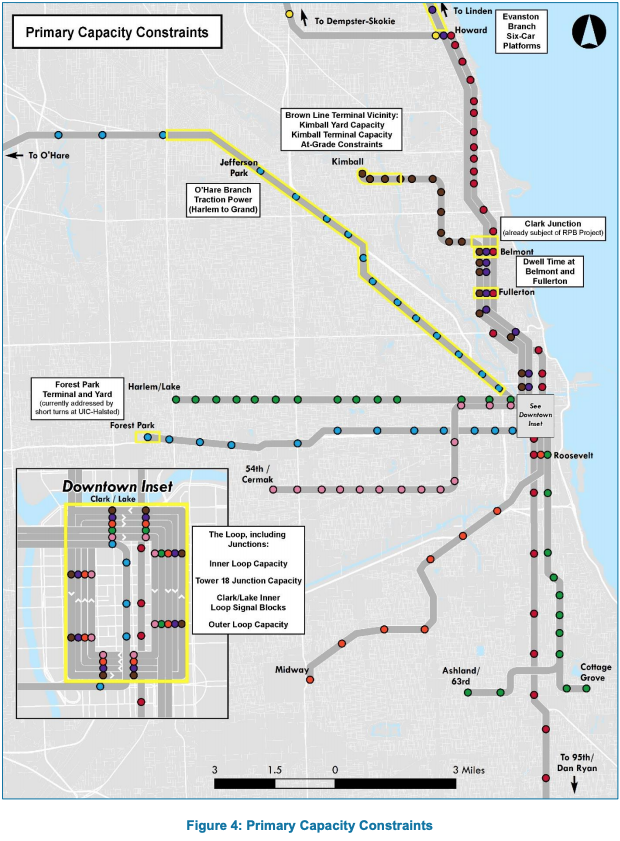

The Loop elevated — where five lines operate — is the biggest primary constraint of the CTA’s train capacity. This was identified in the 2017 CTA System-Wide Rail Capacity Study and it remains unaddressed — this means that the branches that serve the Loop elevated can no longer add additional trains during rush hour. Up until 1964, this issue was dealt with by additional rush hour trains that terminated at stub stations just outside of the physical Loop. The former Chicago Department of Subways and Superhighways addressed these constraints by opening the Dearborn and State Street subways, which allowed riders headed to points on the opposite side of downtown to bypass the constrained Loop elevated.[8]

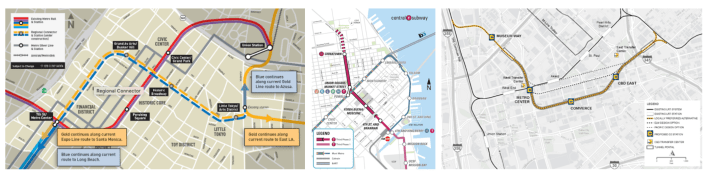

Other cities in North America are dealing with similar issues and addressed capacity constraints on a central “trunk,” similar to the Loop elevated, by building relief lines that add passenger capacity in the central. Look to the Los Angeles’ Regional Connector, San Francisco’s Central Subway, and Dallas’s D2 Subway. These are more like when Chicago built the Dearborn and State Street subways, but they show that increased transit use requires increased capacity on outer branch lines.

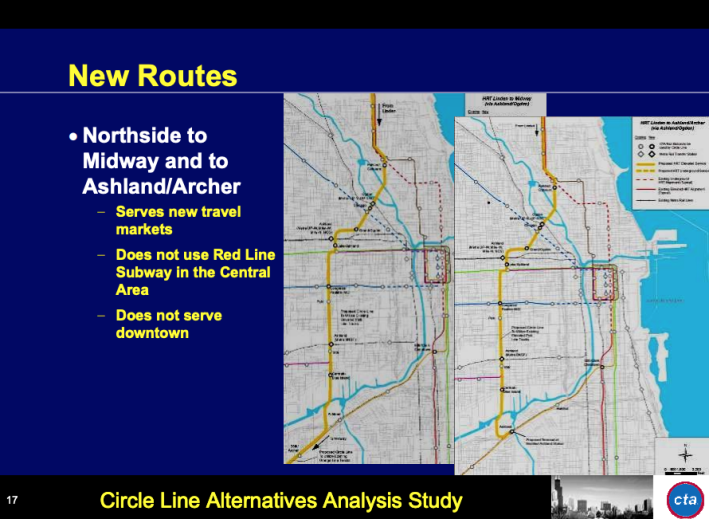

The first proposal that comes to mind is the Circle Line. Yes, the Circle Line would provide connections between places that are outside the Loop. However, if it actually operated as a circle, it would worsen frequency on the outer branches of the Red Line [9].

Instead, it is important to look at this slide from the 2009 Circle Line Alternatives Analysis Study. Instead of running trains through the most constrained portion of the system, the CTA considered running trains directly through the area that is currently seeing so much growth.

It would have been great to have continued developing those concepts so that we would be shovel-ready today with a project to address the new jobs that are outside of downtown, but the bright side is that we can envision a route that serves multiple purposes [10].

Long term, a north-south route on the near west side would serve the 50,000 jobs that might be generated in the North Branch Corridor (Lincoln Yards + environs) better than a proposed “transitway” alone between Lincoln Yards and the Loop.

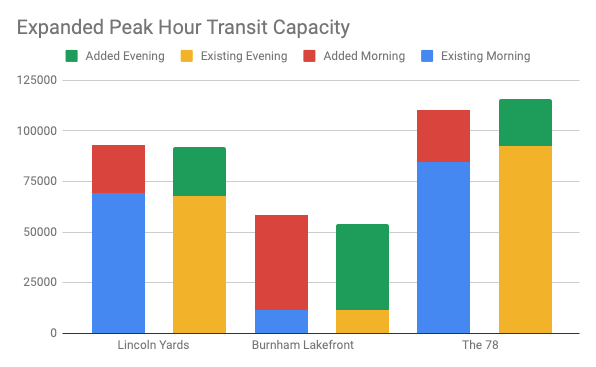

We’ve reorganized the ‘L’ network twice before: Connecting the lines with a consolidated Loop in 1897, and adding cross city capacity via the subways in the 1940s. Now is the time to take advantage of the money and momentum of large redevelopment projects — including The 78 and the Burnham Lakefront [11] — to reorganize our transit system for a future of citywide growth.