Along with other unsung heroes who help keep Chicago moving, from CTA bus drivers to school crossing guards, bike couriers play a key role in making the City That Works work. Nowadays folks doing food delivery on two wheels are a common sight – they’re often spotted with large, cube-shaped insulated backpacks and/or broad, flat “pizza racks” on the front of their rides. By switching trips that would otherwise be done by car or truck to a greener mode, they help reduce traffic congestion and air pollution.

Traditional envelope-and-mailing-tube messengers have similar benefits for the city, but they’ve become less common than they were in previous decades due to the rise of digital communications like email and PDF files. But there are still scores of them working downtown, and some of them have diversified their business by transporting boxes via cargo bikes. They help keep the workday running smoother for downtown employees, transporting crucial documents, plans, and parts from one end of the central business district to the other.

While food couriers and traditional messengers have a generally collegial relationship, and some cyclists do both jobs, there's one sore point. According to some paper couriers, Loop building security protocol heavily favors food delivery folks, who are usually allowed to walk into high-rises via the front door and use the regular passenger elevators. Meanwhile traditional messengers are routinely required to enter buildings through loading docks, and ride the slower freight elevators, which they say is a major time-waster that cuts their earning potential.

One traditional messenger, who asked to be anonymous for fear of being banned from the office buildings he criticized, discussed the issue at length. "At 180 North LaSalle [an office high-rise at LaSalle and Lake], if you’re delivering food you go in the front door and the security guard asks you where you’re going,” he said. “You go up the regular elevators.”

In contrast, he said, if you're a paper courier at 180 North LaSalle, you’re required to enter through the loading dock. “You leave your bag by your bike at the dock, take an elevator down to the sub-floor, and that’s where their freight elevator is. You actually have to take two elevators just to deliver an envelope, whereas anyone else going in that building just takes one elevator."

He noted that it is possible to get around this rule. "You can lie, if you have a backpack on,” he noted. Traditional messenger often wear old-school, one-strap courier bags. “That’s what kind of differentiates between a paper courier and a food courier, at least to anyone looking in. I actually have a backpack, so I tell [security guards] I have food. They don't even ask where I'm from.” But he said he’s sure that if he told the guards that he was delivering an envelope, he’d be ordered to go around to the back of the building and jump through the various time-consuming hoops.

The messenger added that forcing paper couriers to enter through building docks can also expose them to safety hazards. That’s especially true when the docks are located on Lower Wacker Drive, which is essentially a subterranean highway where darkness, high-speed traffic, and damp, slick pavement pose dangers to cyclists.

He singled out the 333 Wacker Drive office building, located at the bend in the drive between Franklin and Lake, as a particularly risk spot for deliveries. To access Lower Wacker at this location, messengers use Post Place, an alley located between Wells and Franklin that slopes down to the river level. From there, the most direct way to get to the 333 Wacker dock is to turn left and ride west against eastbound traffic, which is obviously risky. The blind curve created by the bend in the street makes it even more hazardous to follow the letter of the law by crossing Lower Wacker, biking west with traffic, and crossing again to get to the dock.

The messenger said all of this rigmarole is a major hassle for paper couriers who are trying to get around the Loop efficiently in order to meet delivery deadlines and maximize their earning potential. “Why should I leave my bag?” he asked. “It might seem trivial, but every building you go into, you take on and off a twenty pound bag, all the time. It gets to be annoying."

He estimated that half of a traditional messenger’s day is wasted with building protocol. "You care because the customers rely on you to get there fast. And if you work straight commission [rather than by the hour], that’s your time… It adds up over the course of a day, and when you multiply that by five days a week over the course of a year, that's a lot of time they just waste with their rules, which don't make sense.”

He added that even some building employees raise their eyebrows at the policies. “They don't even make sense to the people who are in the freight elevators with you who have actual freight. The maintenance workers, half the time they’re wondering what you’re doing in the freight elevator."

Asked about the tendency of downtown buildings to have different protocols for food couriers and traditional messengers, Michael Cornicelli, head of the Building Owners and Managers Association of Chicago noted that downtown workers want their meals to show up quickly and at the right temperature. “Food deliveries are different from package deliveries in that a tenant expects the food delivery immediately and is most often waiting in the lobby for delivery,” he said. “Alternatively, package deliveries generally do not have an exact arrival time and may not include an individual’s name. Package deliveries also arrive in a variety of shapes and sizes.” Cornicelli added that, for tenant safety, many buildings direct non-food deliveries to their docks or mailrooms so that the packages can be inspected before they’re brought to the recipient.

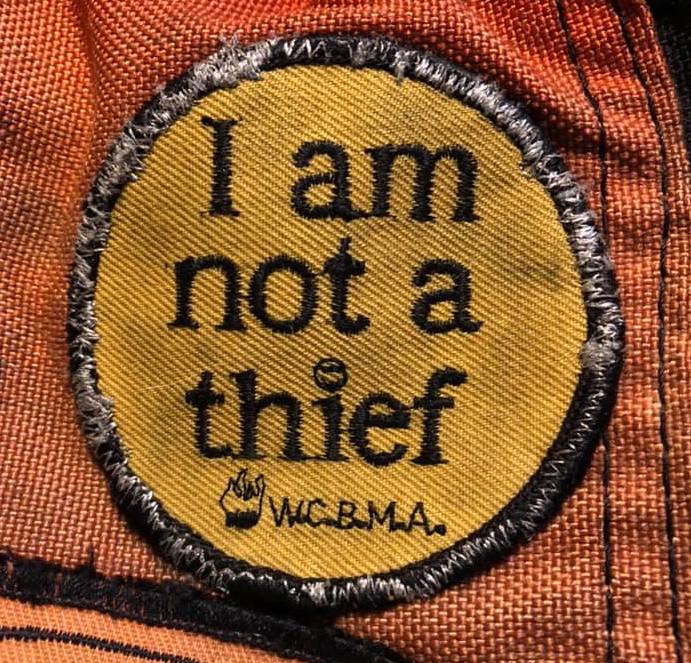

In the past, traditional messengers have argued that they’re singled out for special rules because they’re stereotyped as being potential thieves, and because some white-collar workers don’t like to share elevators with them. But apparently some building managers are willing to make an exception when there’s food involved.

The messenger I spoke with said he’s at a loss as to whom he should speak with about the problem. "The only people I ever talk to are security guards, and they don't have an answer for me -- they're just doing their jobs,” he said. “Seeing as how the buildings have the same sort of protocol, it's safe to assume that they're all following some sort of blanket code.”

Asked whether BOMA might be interested in helping to level the playing field for traditional messengers, Cornicelli indicated that he feels that isn’t his organization’s role. "BOMA/Chicago regularly shares information with our building members about safety and security through our preparedness committee,” he said, but added. “Due to each building having its own set of unique circumstances, we defer to each property management team to implement procedures that best ensure the safety of their tenants."

So, unfortunately for Chicago’s traditional messengers, it may be the case that nothing short of a boycott of the offending buildings will bring about a change in their policies.

This post is made possible by a grant from Freeman Kevenides, a Chicago, Illinois personal injury law firm representing and advocating for bicyclists, pedestrians and vulnerable road users. The content belongs to Streetsblog Chicago, and Freeman Kevenides Law Firm neither endorses nor exercises editorial control over the content.