To simplify the text, unless otherwise noted, I'm using the words "women" and "men" to also include gender-nonconforming people who may be perceived as female or male by others. A version of this article also ran in the Chicago Reader.

In the midst of the #MeToo movement and the wake of the Kavanaugh confirmation, many well-meaning guys have been analyzing past decisions. Some of us have been wondering if there were times when we could have better supported the women in our lives or done more to put an end to the harmful behavior of other men.

Since my field is transportation, I recently asked female friends, colleagues, and anti-harassment activists if it would be useful to share tips from women for guys, covering how to avoid being a jerk, and be a better ally, while sharing public space on foot, on transit, and on bicycles. The goal would be to make the sidewalks, streets, bikeways, buses, and trains safer, more comfortable, and less annoying places. The answer was a resounding “yes,” with dozen of women and gender-nonconforming folks taking part in the conversation via a Facebook discussion and interviews.

Anita Mechler, a librarian, summed up the golden for men who want to avoid causing hassles for women trying to get where they need to go. “Try to be mindful of how you take up space, physically, verbally, and mentally.”

A common thread was that there are a host of issues that men generally don’t have to worry about -- from catcalling to sexual assault -- that are nearly universal, sometimes near-daily, concerns for women moving through the city. Design professional Marie Walz called these challenges “a woman’s experience in patriarchal world,” one that may be invisible to guys, but surely isn’t to the women in their lives.

Take walking home at night, for example. While all Chicagoans have concerns about crime, some told me it’s understandable for women to be wary of any man they encounter on a darkened street, and guys should do what they can to avoid exacerbating those fears. “You can hurt us,” pointed out architecture and design writer Anjulie Rao. “Easily, quickly. We know this. So don’t be surprised when we move away from you, or walk on the other side of the street… It’s never unreasonable.”

Other women suggested that men try to avoid walking less than half a block away from a solo female at night if they’re traveling at the same speed. If it’s necessary to pass her, they said, the guy should leave as much space as possible between them, perhaps saying a quiet “excuse me” as they go, or maybe even cross to the other side of the street themselves.

If you’re a man bothering to read this article, you probably wouldn’t think of making unsolicited sexual comments towards, or otherwise intentionally hassling, a woman walking, or on a CTA bus or ‘L’ car. But do you intervene when you see it happen?

“I would kill to see a man shut another man down for catcalling,” said Hope Nathan, who works in the film industry. “If it’s one of your friends, for the love of Mike, check him.”

SlutWalk Chicago, part of an international movement "working to challenge mindsets and stereotypes of victim-blaming and slut-shaming," provided a statement with advice on what to do if you witness harassment, including getting the woman and yourself to a safe place if there seems to be a risk of violence. On the other hand, they said, “Be aware of how you approach her as well. This doesn’t need to be dramatic so you don’t need to make scene either -- it’s an embarrassing moment.”

Similarly, law student Ezra Lintner, who identifies as genderqueer, said it’s important to follow the lead of the woman who is being catcalled. “I’ve made the mistake of being confrontational when the women I was with just wanted to keep walking… It’s the masculine person’s job to support her decision. A simple ‘Ugh, should we deal with this or keep walking?’ is enough.”

Marketing professional Rebecca Resman had an interesting suggestion for what to do if you see a stranger on the street being verbally harassed. “Start talking to her, or maybe even pretend you know her, so that your convo can override the other person’s.”

When it comes to riding transit, women have a wealth of tips to avoid being “that guy” on the train. The scourge of “man-spreading” is well-documented – men sitting with legs akimbo, encroaching on the personal space of other riders. It’s especially problematic on the newer 5000 series cars, prevalent on the Red Line, that mostly feature tight, aisle-facing bench seating.

Walz brought up a related “don’t” for men on those type of rail cars. When straphanging, “please turn facing the front or the back of the train, so that people don’t have to have your package right in front of their faces.”

Other transit-oriented requests for men included removing backpacks while standing so they don’t wind up in people’s faces, avoiding blocking doors, and not leaning against support poles, so that others can use them as hand grips. Women also asked that guys volunteer to help moms with strollers and elderly women getting on and off buses and trains, and be sure to offer their seats to pregnant ladies. “I kept a log of how many times I was offered seats during my first pregnancy, and it was seriously six times,” Resman noted.

And Walz advised guys that “If a woman has headphones on, she doesn’t want to talk to anyone unless the train is literally on fire.”

Assistant horticulturalist Yaritza Guillen told me that bike commuting has turned out to be a good solution to avoiding the hassles and indignities she regularly faces while walking or riding the CTA. “I don’t have to deal with strange men in my space or creepily talking to me about nonsense.

But while cyclists tend to be politically progressive, that doesn’t mean that bikeways are sexism-free spaces. There’s the phenomenon of “bike mansplaining,” in which male cyclists assume women are ignorant about bike setup or repair, and offer unsolicited, sometimes insulting, advice or assistance. Yasmeen Schuller, owner of the local social networking site The Chainlink, noted that “not all women like being considered a damsel in distress” when they have a mechanical issue. She suggested that men who encounter a female on the street with a bike problem ask if they have everything they need to fix it, rather than assuming that they need help.

Danielle McKinney, a technical trainer at a hospital, recalled attending a seminar on biking to work where the presenter asked the audience members if they knew how to fix a flat. “I raised my hand. He said, ‘You -- you know how to change a bike tire?’"

Bikesplaining even happens to female professional “wrenches” like Mary Randall, who’s also a serious racer. She also reports that during “literally every solo road ride” she goes on in the Chicago area, random men will attempt to “draft” her (ride close behind to cut wind resistance) without saying anything. “So you have this hulking stranger riding two inches behind you, and you have no idea who they are or if they can ride well enough to be that close to you safely.”

How does she deal with that deeply creepy situation? “I just pull over and stop for a few minutes and let them go,” Randall said. “Sometimes I say something like, “If you can’t introduce yourself, get off my f---ing wheel. Sometimes I just blow snot rockets with reckless abandon.”

A number of women spoke out against “man-shoaling,” a topic that requires a bit of explanation. The cycling term “shoaling,” invented by widely-read blogger Bike Snob NYC, refers to the faux-pas of a cyclist cutting to the front of a line of cyclists waiting at a stoplight. Man-shoaling, which may have first been coined by Chainlink members, refers to a guy cutting in front of a woman at a light, under the assumption that he’s going to pass her anyway when the light turns green. “Man shoaling is obnoxious and insulting,” Resman said. “Tip for men: don’t f---ing do that.”

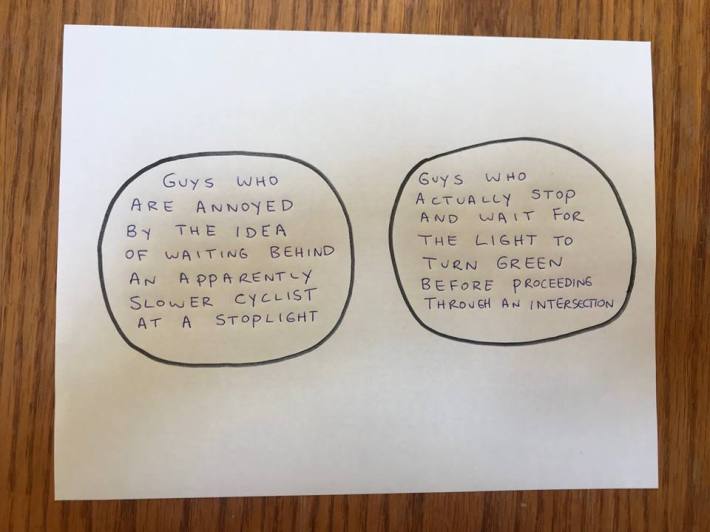

A few men, all of them current or former bike messengers, chimed in on the Facebook discussion to argue that if a man knows that he’s faster than everybody else waiting at a light, based on his skill and steed, it’s unfair to ask him to wait in line. In response, I drew the following Venn diagram to illustrate why this seems to be a non-issue.

Despite all these suggested rules, women also said that men don’t need to walk on eggshells when interacting with them in public space. For example I mentioned on Facebook a tip for men that noted bike frame builder and cycling philosopher Grant Petersen included in his book Just Ride: a Radically Practical Guide to Riding Your Bike: “Don’t chit-chat with solo women you meet [while biking] -- give them their space.”

But some women argued that it’s actually fine for men to strike up a conversation with females they meet in lanes and paths, rather the key is keeping things brief and being mindful of nonverbal cues that the woman isn’t interesting in continuing the conversation. “I met some of my best guy friends and dates because they were chatting me up on bikes,” said artist Aurora Danai.

So, guys, you don’t have to be paranoid that you’re going to inadvertently oppress women as you move around Chicago. But, as Mary Randall said, just remember to “consider how much space you’re taking up, and how that might be affecting the people around you.”