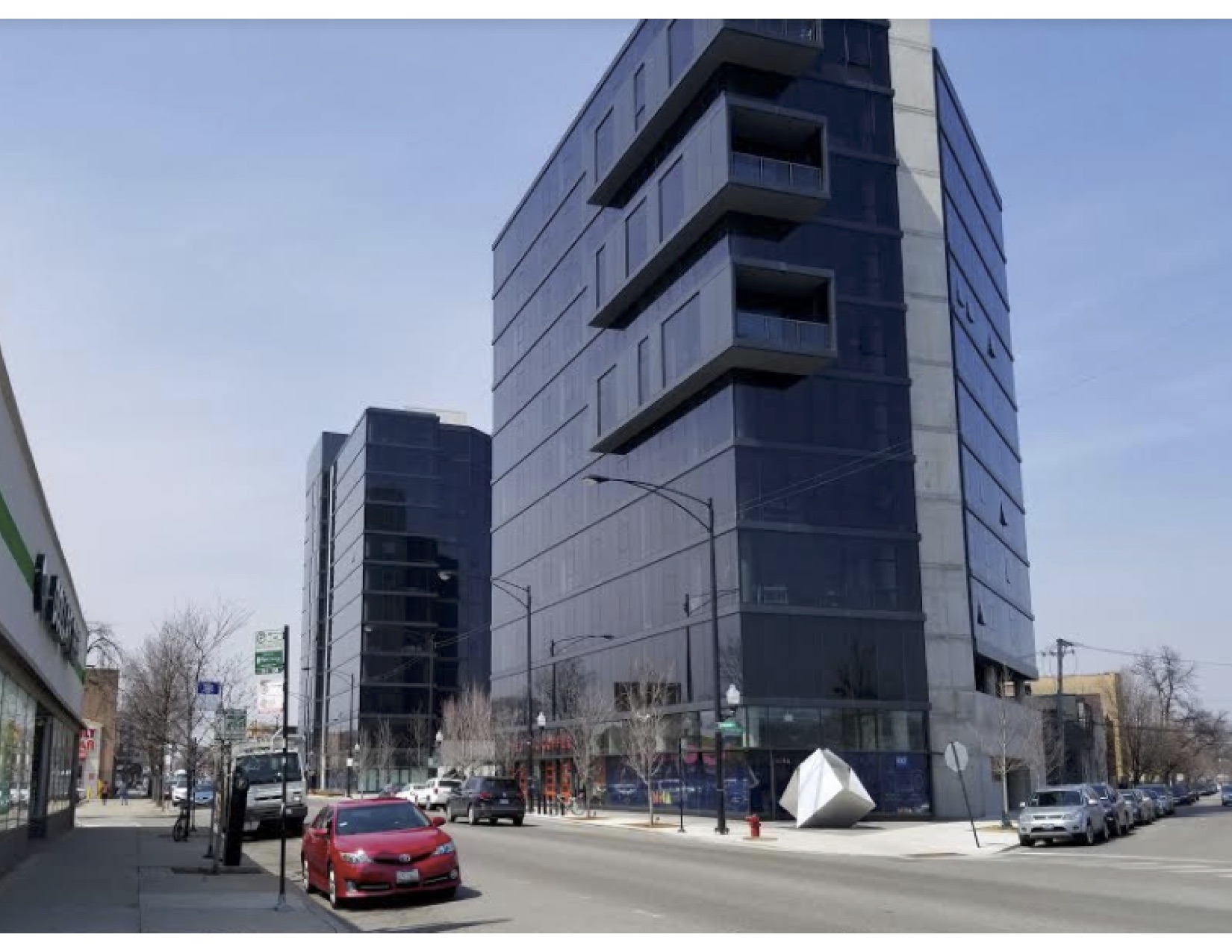

The MiCA transit-oriented development towers, which were erected two years ago at Milwaukee and California (hence the name) near the California Blue Line station, gave Logan Square’s skyline a jolt. At 11 and 12 stories respectively, the buildings rise far above most other structures in the neighborhood and serve as one of the most striking examples of Chicago’s embrace of dense, parking-light, transit-friendly TOD.

During construction of the towers in 2016, affordable housing activists argued that the upscale apartments would drive up property values and housing costs in the neighborhood. Some went as far as to barricade the work site by locking themselves together in a human chain via PVC tubes and buckets of concrete. Some proponents asserted that adding additional market-rated housing in gentrifying neighborhoods takes pressure off the rental market, and noted that ten percent of the onsite units would be "affordable," as defined by city ordinance. The activists countered that the rents for the discounted units still wouldn't be within reach of local low-income and working-class residents.

Setting aside the debate over MiCA's impact on gentrification and displacement, there's a lot to like about the physical structure itself. The towers are definitely TODs: The developer built 216 units with only 59 parking spaces, operating under the assumption that most residents would use the 'L', nearby bus routes, ride-hailing, walking, and biking to get around, instead of driving. And, aesthetically, MiCA isn’t bad by any means. The black glass gives it a distinguished look, and the retail base meets the street well on Milwaukee Avenue, maintaining a pedestrian-friendly environment.

Yet future TODs should not model themselves after MiCA. The towers soar upwards, but most of the development's lot is unbuilt – with only an underwhelming plaza on Milwaukee Avenue and a broad expanse of surface parking on the property to show for it. Chicago developers should learn from MiCA's mistakes and strive for comparable density with less height by building out more of their properties. That way their buildings will fit more neatly into the context of their neighborhoods and avoid aggravating a development-weary public. The future viability of TODs in Chicago requires some degree of public approval (or, at a minimum, their tepid tolerance). But MiCA's height is a factor in why many Logan Square residents dislike the project.

More than half of MiCA’s parcel remains untouched. The development plan originally called for a one-story retail strip along Milwaukee to connect the towers, but that was scrapped just before completion due to a perceived lack of demand for storefront space. In its place, Henry Street Partners added the rather uninspiring plaza.

In effect, the plaza is a waste of developable land that doesn't add much to the neighborhood. On its southern end, Colectivo Coffee has set up a pleasant seating area for patrons, and an adjacent fire installation adds some character. The rest of the plaza, however, leaves a lot to be desired.

Its northern half is just an empty concrete rectangle. The large rocks that were placed in the center of the plaza are tacky. There's almost no green space, making it doubtful many people would want to hang out in the southwest-facing space, especially on hot days. An intimidating rock wall lines the back of the plaza. Behind it, the 59 surface parking spaces consume the rest of the lot.

MiCA easily could have achieved comparable (or even greater) density at a shorter height, if it made full use of its lot. Instead of two large towers, there could have been three mid-sized ones, or any number of other configuration – it’s a large lot. A smaller plaza would have delivered the benefits of the current one, and the surface parking could have become more housing.

Building out versus building up

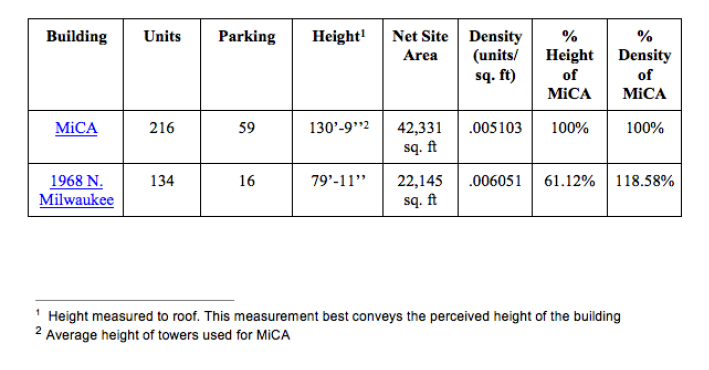

Just a stop down the Blue Line, an under-construction TOD, developed by Clayco, offers a better example for future development. At seven stories, Clayco’s new (currently nameless) apartments at 1968 N. Milwaukee combine height and bulk much better than MiCA. They pack in even greater density, and at seven stories, better fit the surroundings. Clayco built out the lot more fully and will offer fewer parking spaces. The development is next to the Western Blue Line station.

Of course, comparing two developments with unique offerings is difficult, and this general category of “units” does not capture the whole density picture. Moreover, it’s unclear if First Ward alderman Joe Moreno’s office granted Henry Street Partners the regulatory flexibility to reduce MiCA’s parking below the 59 spaces. MiCA was approved as a Planned Development, giving the developers some leeway with zoning in exchange for greater community benefits. Given the controversy MiCA stirred in Logan Square, it’s possible the off-street parking was part of the compromise between developers and the alderman. But, no matter whose decision it was, the outcome is unfortunate – for Logan Square, and, potentially, for future development prospects in the neighborhood.

Preserving Public Support for Development

Development has quickly become a dominant issue in Logan Square. Successive waves of gentrification have moved up the Blue Line and newcomers are pouring into the neighborhood. Many longtime residents have grown averse to new construction projects that they fear will accelerate Logan Square’s transformation and push them out.

This sentiment is clear in the controversies surrounding future development, and in policy moves from local representatives. Last year, 35th Ward alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa announced his intention of downzoning the 0.4-mile stretch of Milwaukee Avenue from Kimball to Central Park in Avondale, restricting how much density developers can build on those parcels. Under Chicago’s system of aldermanic prerogative, aldermen wield immense power over development in their wards. By downzoning, Ramirez-Rosa would gain greater leverage over future projects: Developers would have to ask him for a rezoning to build denser projects. This would slow down development and makes it more costly. According to Block Club reporter Mina Bloom, who has been tracking the proposal, the ordinance is currently stalled in committee at City Council.

Ultimately, downzowning isn’t a longterm solution for keeping Logan Square, or the rest of Chicago, affordable. Our city desperately needs more housing. Subsidized housing is essential, but even more so, the city needs to maintain healthy growth in the number of market-rate housing units.

When the housing supply in a neighborhood doesn't keep up with the demand, home prices and rents can skyrocket. If neighborhoods like Lincoln Park hadn’t blocked so much development in the past, raising housing costs, it’s far less likely that places like Wicker Park and Logan Square would be facing such significant housing pressures today.

Unfortunately, MiCA's overly tall design sets back the cause of development in Chicago by clashing so sharply with its neighborhood. Of course, that's not to say that more context-sensitive development eliminates any backlash to new construction. Nothing will, and 1968 N. Milwaukee had opposition, too. But better-designed development stands a better chance of limiting blowback. Hopefully, this approach will help Chicago's housing supply keep up with demand.