As I’ve written before, Rockford, Illinois, the state’s third-largest city with about 150,000 residents, is an overlooked road trip destination for Chicagoans. Not only is it a Mecca for fans of power-pop legends Cheap Trick (lead guitarist Rick Nielsen still lives in Rockford and is one of its most loyal boosters), but the city also has a lovely riverfront bike trail and a serene Japanese garden, and nearby Rock Cut State Park is a great place to camp. To top it off, the area boasts a completely vegan brewpub – even our vast metropolis doesn’t have one of those.

Soon there will be another great reason for Chicagoans to head downstate to Rockford (assuming that an Illinois city northwest of Chicagoland is still "downstate.") This weekend the Forest City will become a lot greener as LimeBike releases the first fleet of dockless bike-share cycles in the Land of Lincoln. That will make Rockford a great place for Chicago cyclists to experience the technology firsthand. The Chicago Department of Transportation is currently considering whether to let dockless bike-share, aka DoBi ("Dough Bee"), operators set up shop here – more on that in a bit.

LimeBike is based in San Mateo, California, and currently operates in over 50 markets. Last month ex-CDOT deputy commission Scott Kubly resigned from his post as Seattle transportation czar to run government operations for the firm.

Like other dockless brands, LimeBike cycles are left “free-locked” around a city, secured with built-in wheel locks, for customers to locate and unlock via a smartphone app. Partly thanks to having $132 million in venture capital, the company offers low rental prices, $1 for a half-hour ride (compared to a $3 single ride on Chicago’s Divvy system), and a mere 50 cents for students.

While traditional, docked bike-share systems like Divvy typically require a major public investment for the pricey docks and heavy-duty bikes, DoBi bikes are provided for free by the companies. That may make them a practical alternative for smaller cities like Rockford that could benefit from the mobility, health, and economic perks of bike-share, but where it might be challenging to muster political support for purchasing a system.

On the other hand, some bike advocates argue that you get what you pay for. Dockless cycles are typically cheaper, less durable bikes than Divvies, and since they’re usually not locked to a fixed object, many DoBi cities have had problems with sidewalk clutter, vandalism, and theft.

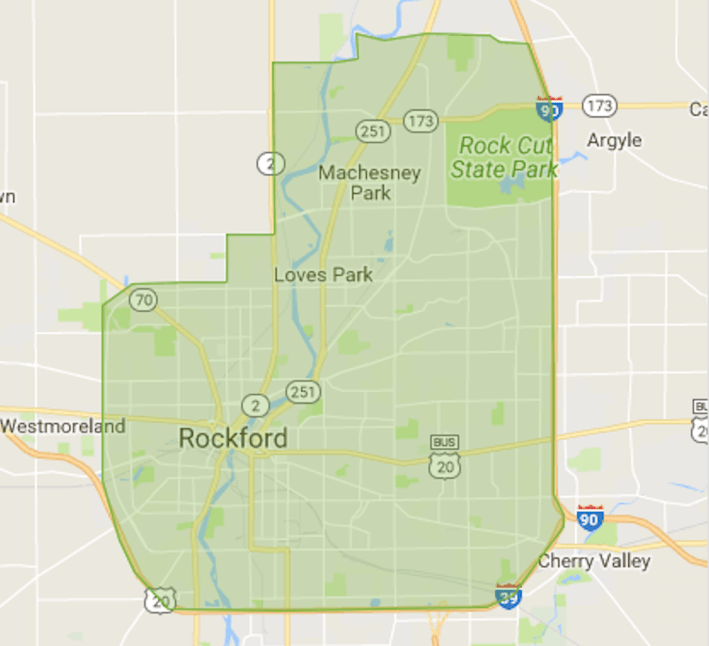

However, Rockford officials say they’re optimistic that dockless bikes will be a positive addition to the region. (The LimeBike coverage area will also include nearby communities like Loves Park and Machesney Park.) “We’re excited to offer a bike-sharing program to the residents of our area,” said Rockford city administrator Tom Cagnoni in a statement. “We researched available options and found that LimeBike was a great fit for the community with a model that does not rely on a big capital investment from community partners.”

But what’s the plan to help ensure that LimeBike will be an asset, rather than a nuisance for Rockford residents? Gabriel Scheer, director of strategic development for the company, who grew up a couple hours north of Rockford in Wisconsin, told me that the enthusiasm of Rockfordians for bringing the system to town makes him confident the bikes will be a success. “There’s been an amazing amount of coordination between the stakeholder groups, including government officials, the business community and citizens, and people are really excited.”

Unlike other cities where multiple DoBi companies operate, the contract grants LimeBike the exclusive rights to provide bike-share in Rockford for three years. Scheer says they plan to release a few hundred bikes by the end of next weekend, eventually building up to about 500 in the near future. Their contract allows them to introduce up to 1,000 cycles, plus additional bikes in increments of 100 with permission from the city. The company has rented a warehouse and hired a couple of local employees, and plans to take on a few more soon.

As for mis-parked bikes, Scheer says LimeBike will work with city officials and the local press to get the word out that the cycles need be locked on the sidewalk or at a bike rack in a manner that doesn’t obstruct pedestrians. He acknowledged that that it's possible some pranksters may throw the cycles in the Rock River. “Regrettably, whether it’s Seattle’s Puget Sound or a lake in Houston, our teams have gotten good with grappling hooks,” he said. “But people eventually become bored with vandalizing the bikes, and in the best-case scenario they might even come to understand that the system can be useful for them.”

The Rockford contract doesn’t allow the city to fine LimeBike if too many bikes are scattered across sidewalks or hung from trees. “But ultimately the city can decide the program isn’t working and shut it down,” Sheer said. “Obviously our goal is for that not to happen.”

The contract also lacks metrics metrics for maintaining the bikes. Scheer said LimeBike’s standard is to check the condition of every cycle at least once a month, but the bikes are typically checked more often then that due to “rebalancing,” when workers redistribute the cycles to keep them from clustering in popular spots. Customers can also report maintenance problems via the app.

Geographic equity is often an issue for bike-share systems. For example, Divvy docking stations were initially concentrated in dense, relatively affluent parts of Chicago, with fewer stations placed in lower-income neighborhoods. Scheer said they’ll be monitoring use patterns in Rockford and rebalancing the bikes accordingly, but in other cities they’ve found that the bikes get good use in business districts and near colleges and universities, as well as in lower-income communities.

Scheer said that after Seattle's Pronto docked system was was shut down, dockless bikes that were introduced to fill the void quickly made their way to economically diverse outlying neighborhoods that had never before had bike-share access. That jibes with what Seattle Bike Blog editor Tom Fucoloro previously told me. (The Chicago-based transportation equity group Equiticity has already worked with community groups on our city's Far South Side and Far West Side to establish "bike libraries" using cycles provided by LimeBike competitors Ofo and Jump, although users have been checking the bikes directly from members of the groups, rather than using the dockless technology.)

Scheer added that Rockford LimeBike members who don’t own smartphones will have the option of calling a number to request that a cycle be unlocked for them remotely. Unbanked residents will be able to use cash to pay upfront for ride credits, and the company plans to make this system easier to use in the near future.

While Chicago city officials haven’t released any information about their dockless decision-making process since December, Scheer told me that in March LimeBike and several other potential vendors met with Chicago Department of Transportation staff. The companies fielded questions about their operations, and then were each allowed 30 minutes to make a private pitch. Yesterday CDOT spokesman Mike Claffey said the department should be providing an update in the near future.

But while our transportation officials make up their minds about dockless, Chicagoans who are eager to give this style of bike-share a spin might consider catching a Van Galder bus to Rockford to do some test-riding. Another option is to bring a personal bike aboard Metra's Union Pacific Northwest line to Harvard, Illinois, and then pedal to downtown Rockford, a 34-mile ride, largely via trails.

Cheap Trick’s Rick Nielsen didn't respond to an emailed request for comment about the LimeBike launch by press time.