[Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield publishes a weekly transportation column in the Chicago Reader. We syndicate the column on Streetsblog Chicago after it comes out online.]

Last month, community organizer Jahmal Cole floated a bold proposal: Eliminate all fares for riding the CTA. As the founder of the My Block, My Hood, My City nonprofit, he often leads underprivileged youth on transit field trips to different neighborhoods.

Some Streetsblog commenters scoffed at the idea. "'I think it should be free,' means he thinks someone else should pay for his transportation, as nothing in this world is free," one reader wrote.

But is it really such a crazy idea from an economic point of view? Transit helps people get to schools, jobs, and preventive health care, and if a higher percentage of current Chicago residents were well educated, employed, and healthy, that could save a lot of money for society. And coaxing more people out of cars and onto buses and el trains would mean less congestion, pollution, and crashes, which would lead to less lost productivity and property damage, lower bills for public health and first responder services, and less wear and tear on roads.

For example, a 2014 study by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found that U.S. traffic crashes cost $871 billion a year in economic and societal costs. Since the city of Chicago represents about 1/120th of the nation’s population, our share of that loss could be roughly $7.3 billion.

The seemingly utopian concept of free transit isn't so foreign in Europe. Estonia's capital city, Tallinn, population 450,000, was a pioneer in this area, rolling out free transit service for residents in 2013. City officials there say that the program is financially sustainable, since it has encouraged more people who live in the region to establish residency in the city. They say the resulting $25 million-plus gain in income tax has more than covered the $15 million in lost fare-box receipts, allowing the city to continually increase transit service to meet demand.

But could complimentary public transportation work in a metropolis as large as Chicago? We may soon find out, since in March Paris's Socialist mayor, Anne Hidalgo, announced plans to study the feasibility of making transit free across the city of 2.2 million in an effort to boost mobility and fight pollution.

Still, when I asked the CTA about Cole’s proposal, spokesman Steve Mayberry indicated that the agency doesn’t consider the concept worthy of serious consideration. He noted that state legislation that has been in place for 70 years requires the transit system to recoup half of its annual operating budget ($1.51 billion in 2018) from fare-box revenue. "This kind of idea has zero successful precedent among U.S. transit agencies," Mayberry added.

It's true that Seattle ended its 40-year-old policy of free downtown transit service in 2012 as a cost-cutting measure. On the other hand, the regional transit system in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, that state's second largest, is still free to ride thanks to funding from local municipalities and the University of North Carolina, and there are plans for a future service expansion.

Chicago transit experts and advocates were also skeptical about whether totally free transit could work here. "Due to our city and state budget problems, we are probably the last metropolitan region in the country that should considering this," said DePaul transportation professor Joe Schwieterman. He added that if the CTA was a free resource, it would create a "tragedy of the commons" scenario where riders would be more likely to abuse the system, amplifying passenger concerns about safety and cleanliness.

Even staff from the progressive Active Transportation Alliance expressed doubt that free rides for all Chicagoans could be feasible under the current fiscal climate. But governmental relations director Kyle Whitehead said the group has been working with UIC's Great Cities Institute about quantifying the burden of transit fares on low-income residents, and how a lack of transportation options prevents many people from getting and keeping a well-paying job. Whitehead said this research could help make the case for reduced fares for low-income residents. (The CTA currently provides reduced or free fares to CPS students, low-income seniors, people with disabilities, and members of the military.)

"Yes, yes, and thrice yes," responded Ronnie Matthew Harris, head of the south-side transportation advocacy group Go Bronzeville, to the idea of income-based CTA fares. "I'd go further and say it should be free for all under 18. Not [just] because of it increasing access, but to help create a generational culture of use of and reliance on public transportation."

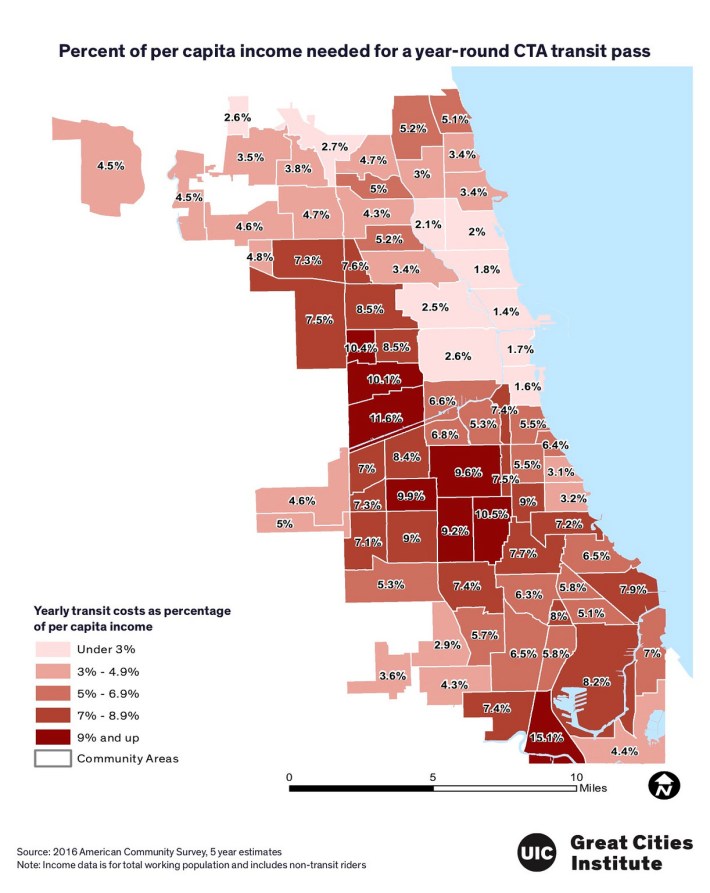

Matt Wilson, an economic development planner with the Great Cities Institute, told me the think tank's research for Active Trans found that in lower-income communities on the south and west sides, the annual cost of buying CTA monthly passes ($1,260) is more than 5 percent of the per capita income for the total employed population. In Little Village the figure is 11.6 percent, and in the Altgeld Gardens area the number is 15.1 percent—a major financial burden.

Wilson added that it would be "incredibly hard" to measure whether reducing transit fares could pay for itself in terms of lower societal costs. "I would imagine that if CTA or the city was to subsidize fares, it would be more of an investment for the social benefit of Chicagoans, not something where cost is intended to be recovered."

Audrey Wennink, a director with the Metropolitan Planning Council, acknowledged that offering free transit for all Chicagoans would be an uphill battle. However, citing last month's Paris announcement, Wennink said that if there is political will in Illinois to address climate change and economic inequality—she noted that about 71.5 percent of CTA riders are people of color and 29 percent are low-income—it might be possible to overcome the financial barrier through creative revenue strategies.

For example, Wennink said, more of the state transportation budget could be shifted from roadways to transit, or tolls could be added to all the highways in the region to fund public transportation. Another idea would be to create a new tax on employers that would be earmarked for transit. About 42 percent of the $12.3 billion annual operating budget for the Paris regional transit authority comes from a tax on firms with ten or more employees.

But if those progressive ideas are nonstarters in a broke, tax-fatigued state like Illinois, Wennink had a couple more modest proposals. The Seattle-area transit authority currently offers the Orca Lift program, with $1.50 fares for residents earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level, similar to Chicago’s Divvy for Everyone discounted bike-share program. Wennink added that cities like Portland, Oregon, have implemented “fare capping,” which means that riders who pay as they go for multiple rides during a given time period never spend more than the price of the equivalent transit pass.

While free CTA for everybody might not be in the cards in the foreseeable future, making public transportation more affordable for low-income residents is a no-brainer. "Making [transit] even more accessible to riders could be great for our region and really distinguish Chicago as a place with high quality of life," Wennink noted.