The Divvy bike-share network has become an important transportation options since in launched nearly five years ago. But many outlying neighborhoods still don't have have docking stations, and many communities within the the coverage area have a low station density, which makes it less convenient to use the system. The docks are expensive, so the Chicago Department of Transportation has tended to concentrate the stations in the most populous parts of the the city. But that means that many less dense neighborhoods -- including lower-income communities that stand to benefit the most from the mobility, health, and economic benefits of cycling -- are missing out.

Dockless bike-share, aka DoBi ("dough bee"), has the potential to fill in some of the gaps in the Divvy system. It typically involves cycles with built-in wheel locks that are left “free-locked” around a city for customers to locate and access via a smartphone app. Since the bikes can be locked up right at your destination, it can be more convenient to use than traditional systems, and since no docks are installed, it can be introduced to new areas quickly and relatively cheaply.

At least 25 U.S. cities currently have DoBi, including Seattle (where it quickly filled the void after the city's docked system shut down), Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, Houston, and Charlotte, North Carolina. A system is supposed to launch this month in St. Louis. New York City officials received applications from 12 dockless companies and are preparing to launch a pilot this summer.

However, there are plenty of possible downsides to DoBi. The companies have an incentive to release as many cheap bicycles as they can get away with in order to maximize market share, which has resulted in massive graveyards of busted cycles in Chinese cities. Poorly parked free-locked bikes can be an eyesore at best and a tripping hazard at worst. In Dallas, which has the most DoBi cycles of any American city but little cycling infrastructure, the bikes seem to be vandalized almost as often as they are ridden.

And the artificially low rental prices of the venture capital-backed DoBi services could cannibalize successful traditional systems. For example, Divvy's new $3 single-ride fare is three times as expensive as a typical dockless trip. There's also the question of whether dockless companies will serve all neighborhoods in a city fairly, or simply focus on the most profitable ones.

To help ensure that DoBi does more good than harm for cities moving forward, two Chicagoans have written a new report recommending guidelines regulating the technology. City of Chicago officials, who are currently considering whether to let dockless companies set up shop here, would be wise to give it a read.

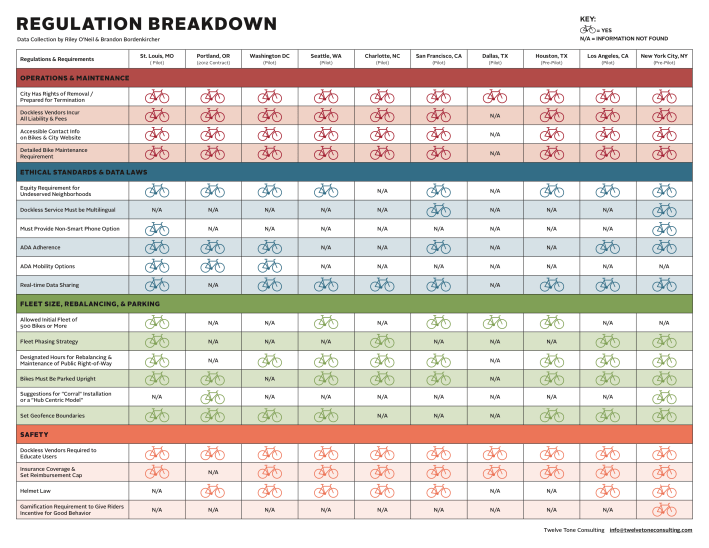

"Dockless Bikes: Regulation Breakdown" reviews existing agreements between U.S. cities and dockless companies and highlights best practices. The report was written by Brandon Bordenkircher and Riley L. O’Neil from Twelve Tone Consulting, a local government affairs consulting company. O'Neil also volunteers for Equiticity, a Chicago-based transportation justice group led by Oboi Reed, who has been promoting DoBi as a solution for bringing shared bikes to underserved South and West Side neighborhoods.

The study reminds city officials that they have the power to make dockless vendors comply with requirements, and explains all the different business rules and regulations that a city could adopt to promote a DoBi system that doesn't clutter sidewalks and provides equitable service.

For example, the authors recommend, cities should reserve the right to relocate or confiscate poorly parked bikes that are blocking the public way or causing other problems. The vendors should be liable for all liabilities or fees, such as if someone trips over a bike lying on the sidewalk, or if money has to be spent retrieve a bike that pranksters have thrown in a river. The companies should be held to certain standards for maintaining the bikes and "rebalancing" them so that they don't cluster in particular locations.

The report discusses strategies that various cities have used to promote equity. St. Louis and New York are requiring the companies to provide a way to check out a bike without using a smartphone. Other municipalities have required DoBi providers to offer adaptive bikes for people who cannot ride a standard bicycle.

The study also talks about ways to ensure equity in coverage. Both New York and Los Angeles are mandating that dockless companies only operate areas not already served by the existing docked systems. In NYC, that includes large sections of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, plus all of the Bronx and Staten Island. However, an argument for not having such a rule in Chicago is that many parts of the Divvy coverage area with low station density would benefit from also having DoBi cycles to fill in the gaps.

Data sharing is another key issue that city officials must consider. Dockless providers collect plenty of data from the apps that users must install on their phones, and selling this data to other companies may be part of their profit strategy. Municipalities should negotiate robust data-sharing agreements to give city planners, transportation advocates, and the public useful info about usage patterns.

Bordenkircher and O'Neil provide specific advice for CDOT, recommending that officials limit the companies to a conservative number of bikes at first to minimize problems as residents get used to the new system. For example, Washington, D.C., which already had a successful docked system, let Dobi providers launch their systems by releasing a maximum of 400 bikes per company.

The report includes feedback from industry professionals as well. For instance, one bike-share planner said DoBi vendors should be encouraged to establish "bike corrals" to aggregate dockless bikes into a single dedicated space on a sidewalk on each block where there are many competing demands for sidewalk space. However, the planner suggested, a city cannot rely on this process alone, and an agreement should stipulate a sufficient rebalancing process to move bikes around in case the corrals become crowded themselves.

In mid-December CDOT announced that it planned to invite DoBi vendors to present their proposed business models and ideas in the next month or two and use that info to inform future city policy. More than three months later there have been no official updates, but O'Neil says dockless company reps told him the department talked with multiple firms in March. CDOT spokesman Mike Claffey promised to provide more info soon.