[Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield publishes a weekly transportation column in the Chicago Reader. We syndicate the column on Streetsblog Chicago after it comes out online.]

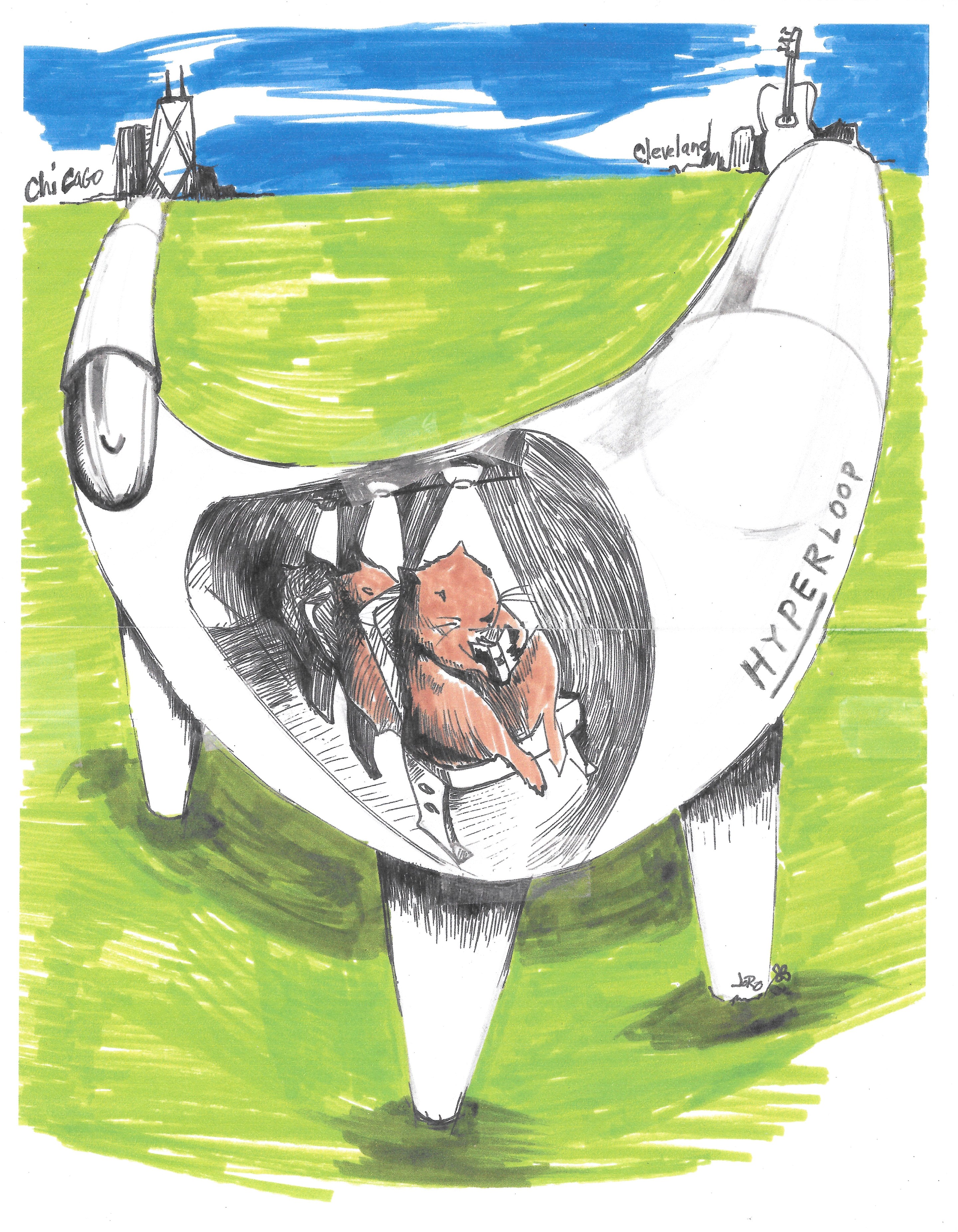

The polished promotional video for what’s being promoted as the world’s first Hyperloop route, between Chicago and Cleveland, features a rough-voiced narrator extolling the no-nonsense virtues of the Midwest. Hyperloop Transportation Technologies claims that within three to five years they can build a 340-mile corridor of near-vacuum-sealed tubes on pylons for shooting passenger in pods as fast as 760 mph, reducing the journey to less than 30 minutes.

“Where do you go to make dreams, to build them with metal and glass and your own two hands?” the narrator says as the camera gazes up at Chicago’s sloping, mist-enshrouded Chase Tower before the clip cuts to other rust belt skyscrapers and an Art Institute lion. “You go to cities like Cleveland and Chicago, Pittsburgh and Detroit… The Midwest is a place that drops its welding mask over its face and gets to work.”

But what the video doesn’t tell you is the technology doesn’t actually exist yet, they don’t yet have the land to build it, and you might not even be able to survive such a high-speed journey.

Still, this Jetsons-esque project has political momentum. On February 26 civic leaders from northeast Ohio, a region that’s desperate for an economic shot in the arm, gathered for the signing of a $1.2 million grant agreement to pay for a six-month feasibility study for the route. The sum includes $400,000 in federal planning funds via the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency, plus $200,000 from the Cleveland Foundation, matched by $600,000 from HTT. Nine midwest congressional reps, including Chicago’s Bobby Rush, recently sent a letter of support to Donald Trump, and the Illinois Department of Transportation has committed to helping out with the project.

The Hyperloop craze launched in 2013, when tech guru Elon Musk introduced and named the concept. (Musk is currently vying to build the O’Hare Express route using a similar scheme he called a “high-speed Loop.”) A few different companies are currently trying to pioneer the Hyperloop, and several different corridors are being brainstormed around the country. In late February HTT’s competitor Virgin Hyperloop One joined forces with the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission for another Buckeye State route, linking Columbus to Chicago and Pittsburgh.

The grand plan of these Hyperloop boosters is a network of space-age hamster tubes linking the entire Great Lakes region to the eastern seaboard. They argue that this environmentally friendly mode, featuring passive magnetic levitation and electric propulsion, fueled by solar energy and other sustainable sources, will solve problems of congestion and pollution while making it exponentially faster to transport people and freight between cities.

HTT projects that its Hyperloop will be able to carry 54,720 customers a day between Chicago and Cleveland for about $20 a ticket. And, despite the fact that nowadays the Forest City’s airport is struggling to draw enough traffic to survive, the company says it’s confident the Hyperloop service can be profitable, with no need for a government subsidy. (The thinking is that the government-subsidized study will help prove that.)

There’s just one problem: A passenger-safe Hyperloop doesn’t actually exist yet. While the gruff-voiced narrator assures us that “We’ve already got a prototype,” he’s referring to a not-to-scale model Virgin Hyperloop One is testing in the desert outside of Las Vegas. In December an unmanned pod set a record at 240 mph, but that’s less than a third of the target speed.

Since no one knows yet whether a full-size, full-speed Hyperloop could carry human cargo safely and comfortably, does it make sense to invest hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxpayer money to plan a route? And, as Illinoisans, should we be concerned about this potential boondoggle diverting resources from other worthy projects?

For example, in 2013 transit analyst and mathematician Alon Levy deconstructed Elon Musk’s white paper for a Hyperloop from San Francisco to L.A. He noted that Musk estimates for engineering and land acquisition costs were about a tenth of market rates. Moreover, Levy said, Musk failed to fully account for the g-forces that supersonic ground transportation would have on the human body, which would result in a terrifying “barf ride.” The press release for the Chicago-Cleveland project promises that that customer comfort would be maintained through “methods of limiting the force felt by passengers during the critical acceleration braking phases.”

HTT spokesman Ben Cooke told me that the company is currently building out test facilities in Toulouse, southern France, and hopes to test a full-scale system later this year, although he didn’t confirm that the trial would include passengers. He argued that the technology to create the Hyperloop already exists on the market today and said the system has been validated as realistic by third parties including NASA. “Most recently one of the world's largest reinsurance companies, Munich Re declared our system to be feasible and insurable.” (Munich Re also acknowledged that the challenge of building the system would be “extreme.”)

Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency director Grace Gallucci, who formerly served as deputy director of Chicago’s Regional Transit Authority, argued that the $1.2 million will be money well-spent. “We’re pretty confident that the Hyperloop is going to happen – it’s just a matter of where and when. We want to have the benefits of being early adopters.”

Illinois Department of Transportation spokesman Guy Tridgell said that while his department recently signed a memorandum of understanding with NOACA, IDOT hasn’t budgeted any funding for the project. “They’ve asked us to help them with some research on this,” Tridgell said. “We’re donating some staff time, but that’s about it. We like to view ourselves as an innovative department, so if there’s something in the private sector that could help grow our economy and improve our connections to other economies, that’s worth investigating.”

DePaul University transportation expert Joe Schwieterman believes IDOT’s approach makes sense. “There’s plenty of reason to test the waters and see if momentum builds for something this dramatic,” he said. “You don’t want to be like the guy in the 1920s who said, ‘We’re never going to have ubiquitous air travel all across the country.’”

On the other hand, Schwieterman argued that there’s an opportunity cost for setting aside a significant amount of money for doing such a speculative project. He contrasted the Hyperloop research project with a study IDOT conducted a few years ago looking at the feasibility of running French-style high-speed rail between Chicago and Saint Louis, capable of exceeding 200 mph. “That’s technology that’s ready to go.”

Schwieterman added that a possible “fly in the ointment” for the Chicago-Cleveland plan route could be the difficulty of getting federal approval for such a radical new form of transportation. “A lot of assumptions are being made that safety issues are going to be quickly resolved, but I see no evidence that the U.S. Department of Transportation is going to fast-track this project.”

Rick Harnish, director of the Midwest High Speed Rail Association argued that the HTT is also underestimating the difficulty of getting right-of-way access, especially since traveling through a tube at the speed of sound will require that the route have few or no curves. “That’s what really galls me,” he said. “These Hyperloop guys think that the barrier to high-speed travel is technology, but the real problem in this country is right-of-way. Do they think they can get permission for a straight line from Cleveland to Chicago in three to five years?” He added that even though the tubes would be raised above the ground on pylons “people are not going to want this in their backyard any more than an attractive high-speed rail line.”

Harnish noted that, in order to maintain a cost advantage over rail, the Hyperloop pods will need to be much less roomy than a train car. Moreover, they won’t have windows, and passengers will need to stay strapped in their seats for the duration of the trip. “That doesn’t seem like a very attractive way to travel. And what if you need to use the restroom?”

Still, Harnish agrees with Schwieterman that it’s appropriate for IDOT to be involved in the feasibility study. Even if the Hyperloop scheme turns out to be a bust, Harnish argued, the report could be a boon. “I hope that it demonstrates that there’s a market for this route and, as a result, the states wind up building high-speed rail.”