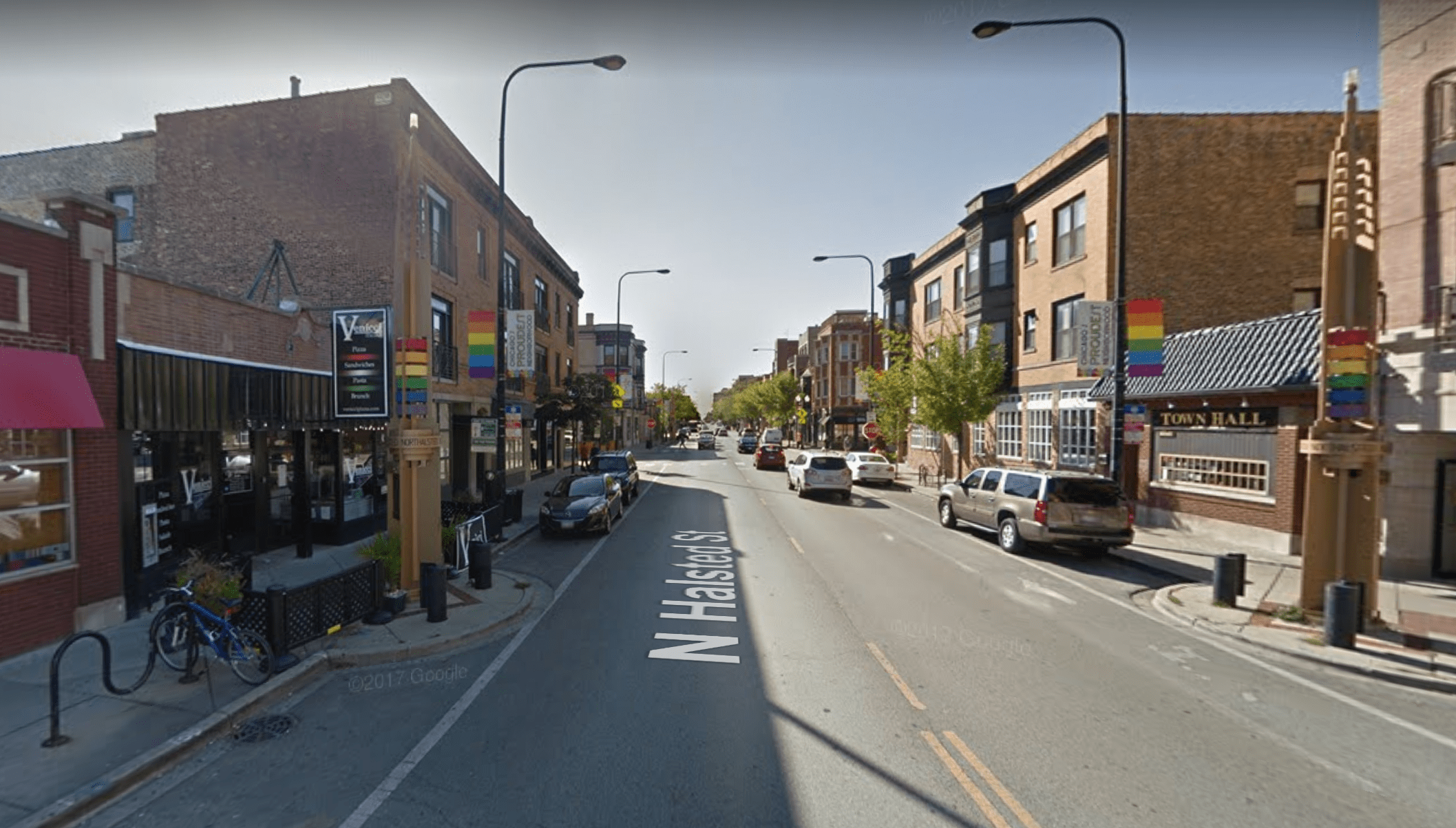

This spring will mark the second year of an expanded weekend parking ban on a half-mile stretch of Halsted Street between Belmont and Addison in Boystown. The parking restrictions were originally piloted in 2011 on the short segment of Halsted from Belmont to Buckingham Place, with parking banned between midnight and 5 a.m. Saturdays, Sundays and Mondays from spring through early fall.

Last August the restrictions were extended to Addison and expanded to start at 11 a.m. At the time, Chris Jessup, an assistant to 44th Ward alderman Tom Tunney, told the website ChicagoPride.com that the parking program was implemented in partnership with the 19th Chicago Police District, the Northalsted Business Alliance and community members. "The goals of this police order pilot program are to improve vehicular and pedestrian safety on Halsted and to discourage public drinking and loitering in and around parked vehicles," he said, referring to gatherings residents have dubbed “car parties.” Tunny's office did not respond to requests for a comment for this article.

The website CWB Chicago, which covers crime in Lakeview, reported in August that the restrictions were implemented after neighbors, many of them residents of a condominiums near Belmont and Halsted, complained about “late night music blasting from parked cars, dancing on sidewalks, and drug dealing.” (It’s interesting that dancing on the sidewalk in a buzzing nightlife district is considered a bad thing.)

“Essentially, the problem is people loitering or ‘hanging out’ without any reasonable purpose,” local police commander Marc Buslik said, according to CWB. “[They’re not] patronizing the businesses or visiting residents.”

Last week Crain’s Greg Hinz, who lives in the area, reported that Tunney has said another reason for the ban is to clear up curbside space so that ride-hailing drivers can pick up and drop off passengers without double parking, which stops traffic on the two-lane street.

While the ban is reportedly popular with local residents, and the parking restrictions don’t seem to negatively affect businesses, some of the explanations for the policy raise class and race issues. Are the restrictions simply an effort to prevent illegal behavior (and traffic jams), or is there also a question of exactly who is welcome to hang out on Halsted?

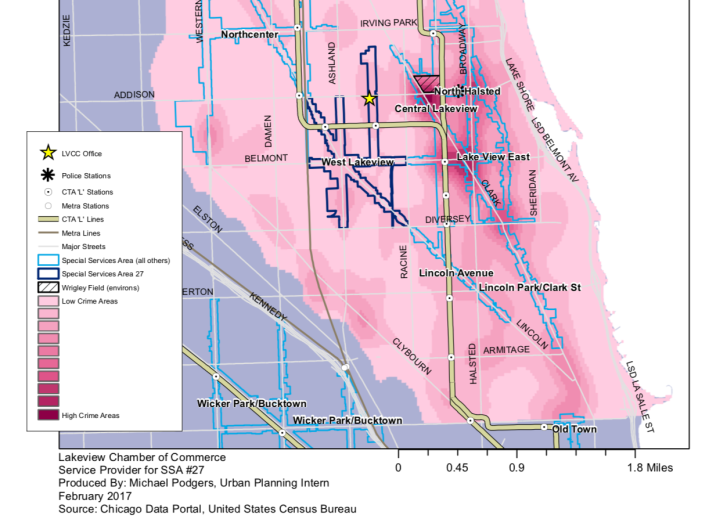

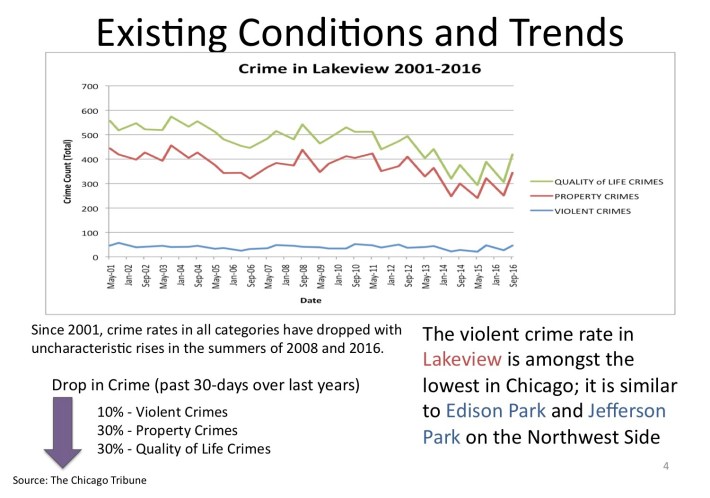

While crime has grabbed headlines in Boystown in recent years, statistics suggest there’s a disconnect between residents’ perceptions of its prevalence and the reality. According to Chicago Tribune data, Lakeview is among the city’s safest neighborhoods, on par with predominantly residential ones on the far Northwest Side, such as Jefferson Park and Edison Park. This is in spite of Lakeview being home to two of the city’s rowdiest nightlife areas—Boystown and nearby Wrigleyville.

When you map crime incidents in Lakeview, the parking ban strip does have a higher density of illegal activity than some other parts of the neighborhood, and the Belmont/Clark/Halsted area is a hotspot. But it pales in comparison to the density of crime around Wrigley Field and the surrounding Wrigleyville bar district. While Wrigleyville’s sports bars attract a predominantly straight, white, middle-class clientele, Chicago’s gay village attracts a much more diverse crowd, because it functions as a Mecca for LGBTQ people from all over the city and suburbs regardless of race and class.

It’s notable that the idea that Boystown has a crime problem picked up speed not long after the Center on Halsted community center, which offers counseling services, STD testing, after-school drop-in programs, and other services, opened in 2007. This landmark further attracted LGBTQ people seeking resources tailored to their needs, as well as a safe, judgment-free place to hang out and be themselves. This includes many youth, people of color, and lower-income individuals who don’t fit the mold of the stereotypical white, more affluent Boystown bar patron.

Sadly, it is their presence that may be behind the perception that crime is on the rise and the streets are becoming more dangerous. This issue came to a head in 2011 when LGTBQ youth of color held protests asserting that they were being scapegoated for crime and racially profiled when they visited the area.

Of course, just because some residents believe that there’s a crime problem doesn’t mean that a neighborhood is actually less safe than other parts of town. In his book “Boystown,” sociologist Jason Orne examines the perception and reality of crime in the area and points to studies that show an increase in the presence of people of color in a community often correlates with residents sensing crime has gone up, even when it stays constant or drops. This is the case in Boystown. Indeed, Lakeview has seen an overall decline in crime incidents in recent years.

Normally a livable streets advocate like myself would applaud a parking ban that makes it easier for people to access a popular nightlife district without driving there. But the Boystown restrictions are troubling because they seem to have the intention of discouraging people from spending time a neighborhood that's supposed to be a haven for them, simply because they don’t have the money to buy drinks in nightclubs or know people who live in pricey condos.

The ban is troubling because it reeks of thinly veiled racism and classism towards Black, Brown, and lower-income LGTBQ people who want to enjoy themselves in a queer-friendly neighborhood, just like other Halsted Street visitors. This policy restricts access to public space under the pretense that “hanging out” and dancing on the sidewalk by people who can’t afford cover charges and cocktails is inherently problematic, while drinking and dancing in clubs by people with thicker wallets is not.

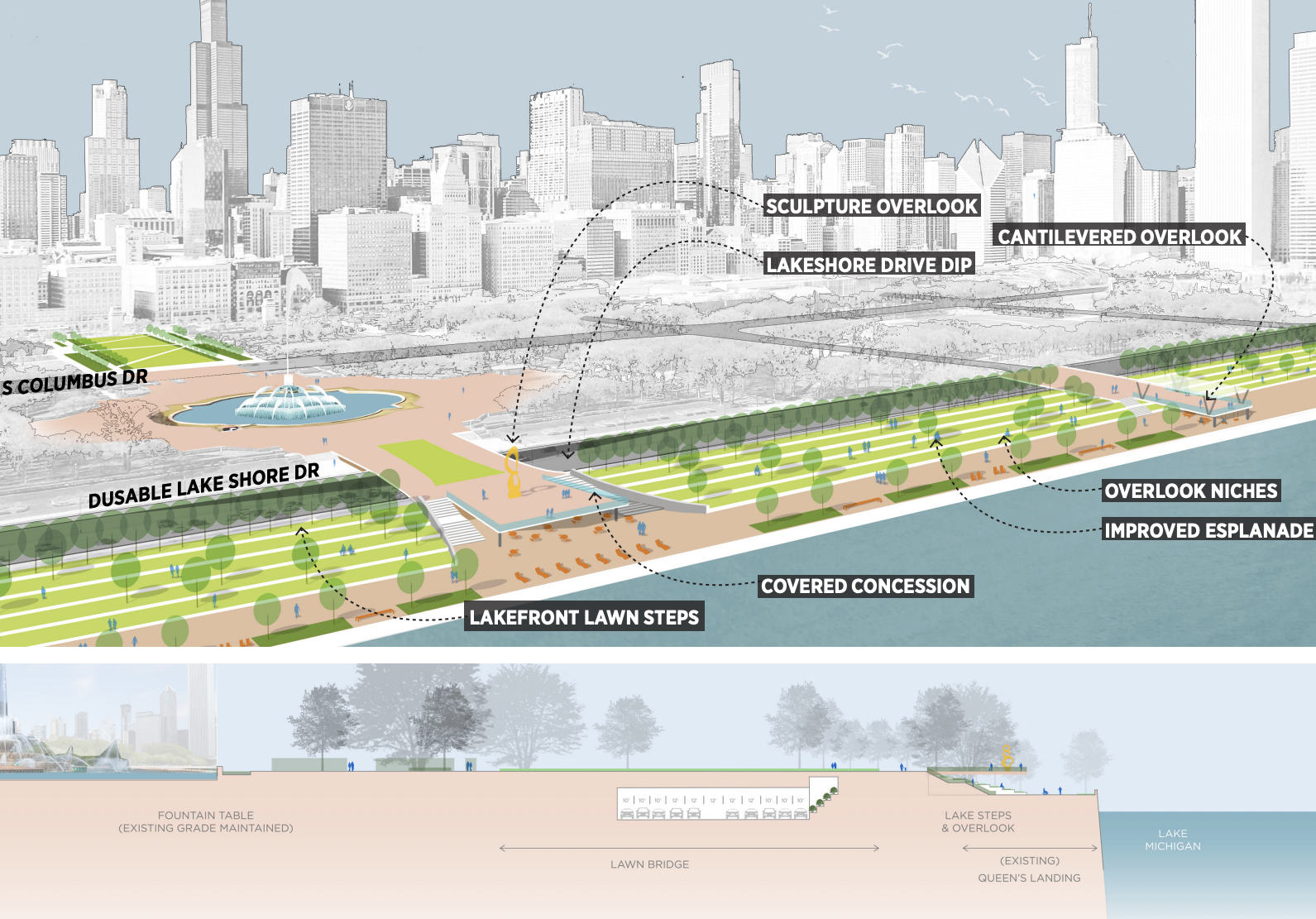

As it stands, the ban makes it easier for police to target visitors of color or lower incomes, which makes Boystown less welcoming to people who don’t have the same economic or social support systems as wealthier denizens. If the restrictions are truly needed, a better approach would be to pair this strategy with public space initiatives like wider sidewalks, seating areas, pocket parks, and affordable food trucks. That would invite people of all backgrounds and income levels to come spend time and be themselves in the gay village.

Correction 2/6/18 5:45 PM: This post previously incorrectly stated that there is no nighttime parking ban in Wrigleyville. There actually is a parking ban on Clark Street near Wrigley Field on Saturdays and Sundays from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m. I apologize for the oversight. -- John Greenfield, editor