At the second of three West Side Vision Zero community input meetings held this week, residents discussed what part they'd like to see the police play in their communities as part of the city's campaign to eliminate traffic deaths by 2026. During the hearing at Garfield Park's Legler Library, some argued that, due to the department's widely documented issues with civil rights abuses, the police shouldn't be involved with Vision Zero in communities of color at all.

The city launched Vision Zero this summer with an outreach program focused on the West Side communities of Garfield Park, North Lawndale, Austin, and the Near West Side, some of the most crash-prone neighborhoods in Chicago, funded by a $185,000 grant from the National Safety Council. Four Vision Zero outreach workers, dubbed "community organizers," have appeared at 130 local events, collecting input from neighbors about their traffic safety concerns. The first of the three community meetings was held Tuesday in North Lawndale, and the final hearing takes place this Saturday from 1-3 p.m. at Austin Town Hall, 5610 West Lake.

Public policy consultant Amara Enyia introduced the Garfield Park meeting by noting that the purpose of the outreach process is to help create a Vision Zero strategy that accurately reflects the will of residents. "This is a safe space," she said. "Please be as candid as you can. This is the only way that the plan will be an accurate reflection of your thoughts and concerns."

Rebekah Scheinfeld, commissioner of the city's transportation department, which is spearheading Vision Zero, then addressed the room, noting that about 2,000 people are seriously injured or killed in crashes on Chicago streets each year. "It's a number that's completely unacceptable," she said. "Crashes are, for the most part, preventable." For this reason, she argued that traffic collisions should be referred to as "crashes, not accidents." The commissioner added that she herself has been a victim of traffic crashes at multiple points in her life.

Scheinfeld noted that the West Side focus neighborhoods have been disproportionately impacted by traffic violence, with 900 people seriously injured or killed between 2010 and 2014 (the most recent year for which official state crash data was available before the city's Vision Zero plan was written.) She then outlined different possible strategies to combat the problem, including engineering (safer street designs), education, and enforcement. "We're committed to policing traffic laws fairly and educating drivers about dangerous behaviors," she said.

Next, Vision Zero community organizer DeAndre Bingham shared a story about why fighting traffic violence is a personal issue for him. "I never really understood the true meaning of traffic safety... until I lost a friend to a car crash, to a person that was drunk, doing 90 mph down a 40 mph street." He said this loss motivates him do everything he can to prevent others from experiencing the same heartache.

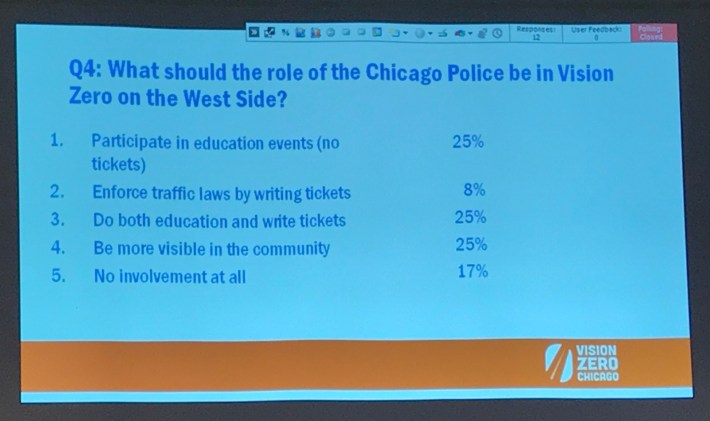

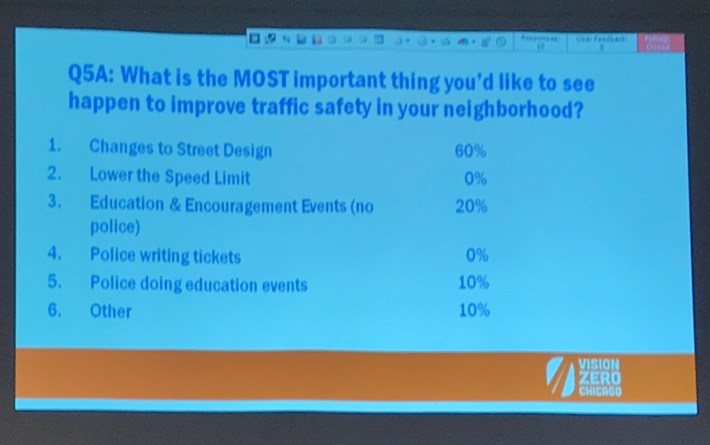

Bingham and fellow organizer Shameka Turner then led the attendees in a live survey about their commuting habits and views on various Vision Zero strategies, handing out electronic clickers that provided instant survey results that were projected on a screen. When it came to what role police should play in the campaign on the West Side, some participants supported safety education efforts by officers, ticketing, or a combination of the two, while others called for a more visible police presence, but some said there should be no police involvement at all.

North Lawndale resident Barbara Stewart called for more police visibility. "I would like to see -- and I hesitate to say it with officers in the room -- foot patrols! I live two blocks from a police station and I've never seen an officer walk down my street." She argued that this tactic would make officers better attuned to what's going on in the neighborhood and would improve community relations.

Slow Roll Chicago, which promotes biking on the South and West Sides, has previously called for the city to remove enforcement from the Vision Zero Plan, arguing that a police department that is nationally known for civil rights violations by officers should not be given the opportunity to increase its activities in communities of color. The group recently launched an online petition on this issue, which has garnered almost 300 signatures.

According to a recent blog post by cofounder Oboi Reed, Slow Roll leaders met with staff from Mayor Rahm Emanuel's office and the Chicago Department of Transportation last Friday to discuss their concerns. Reed says the city officials weren't on board with the request to remove enforcement form the plan, but they did agree to share ticketing and crash data for a future Slow Roll study, as well as to meet again after this week's hearings.

"We fully support the goal of Vision Zero and we believe we can get there by prioritizing engineering and education, not police enforcement in communities of color," Reed said at yesterday's meeting. "We are not suggesting that the Chicago Police Department stop doing their jobs. We expect them, and we pay them, to enforce traffic laws and criminal laws."

"Our concern is about the the risk to people of color, the risk of over-policing, the risk of our communities being further criminalized or worse," Reed added. "We've seen it, we've read about it, we've seen the video footage. We know the potential for what can happen when structural racism is a part of the Chicago Police."

Stewart agreed that Vision Zero could potentially give the officers another tool for harassing residents by using traffic enforcement as a pretense for otherwise unconstitutional stop-and-frisk policing. "We have to figure out another way forward." However, she added that ticketing the most dangerous driving behaviors might be helpful, if it's possible to ensure that it's done fairly.

A young woman in attendance argued that police officers sometime seem to be heavy-handed with traffic enforcement on the West Side. "I don't think there needs to be six different police cars involved in one traffic stop."

Turner acknowledged these concerns about policing, noting that it's important to consider any unintended consequences that could occur from enforcement efforts. She noted that during the North Lawndale meeting, a Latina resident mentioned that any interaction with officers, even as part of traffic education efforts, can cause anxiety for undocumented immigrants who fear deportation.

Turner handed out laminated pages with examples of traffic safety infrastructure such as sidewalk bump-outs, pedestrian islands, speed humps, traffic circles, and speed feedback signs. Stewart said she wasn't a fan of some of the traffic calming strategies, arguing that drivers will often speed to a hump, slow down to go over it, and then speed the next one. "All they do is tear up my car."

Stewart also noted that some residents may view new infrastructure as a harbinger of gentrification. "It seems that these changes and upgrades are being enacted not for the residents but for the future residents as part of the changing complexion of the West Side," she said. "With that comes increased costs and [property taxes] and you present it to me like, 'Oh, this is a gift.'"

"I hear you," responded Turner. "At out first meeting we were talking about bike lanes and people were like, 'Bike lanes aren't for us, they're for them.' And I was like, 'Well, I kinda ride a bike, and I kinda want to be safe.' The bike lanes can be for everyone."

This post is made possible by a grant from Freeman Kevenides, a Chicago, Illinois personal injury law firm representing and advocating for bicyclists, pedestrians and vulnerable road users. The content belongs to Streetsblog Chicago, and Freeman Kevenides Law Firm neither endorses nor exercises editorial control over the content.