[The Chicago Reader publishes a weekly transportation column written by Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield. We syndicate the column on Streetsblog after it comes out online.]

On June 12, the city of Chicago finally released the Vision Zero Action Plan to eliminate serious and fatal traffic crashes, years after peer cities launched similar programs, about six months later than originally planned, and not a moment too soon. After all, more than 2,000 people are killed or seriously injured in our city each year, with an average of five serious injuries each day and a death every three days. The plan, which was crafted with input from a dozen city departments and agencies, led by the Chicago Department of Transportation, has the stated goal of achieving zero serious and fatal crashes by 2026.

“Chicago has made progress in making our streets safer, but we still experience far too many traffic crashes,” Mayor Rahm Emanuel said in a statement at the time. “The status quo is unacceptable,” Mayor Emanuel said. “We will streamline our efforts to protect the lives, health and well-being of all Chicagoans.”

The new plan, which covers the next three years of the decade-long safety push, includes several ambitious, but hopefully realistic, benchmarks to reach by 2020. It seeks to reduce deaths from traffic crashes by 20 percent from the 2011-2014 average of 111 per year to 89, and serious injuries by 35 percent, from the four-year average of 1,896 to 1,232.

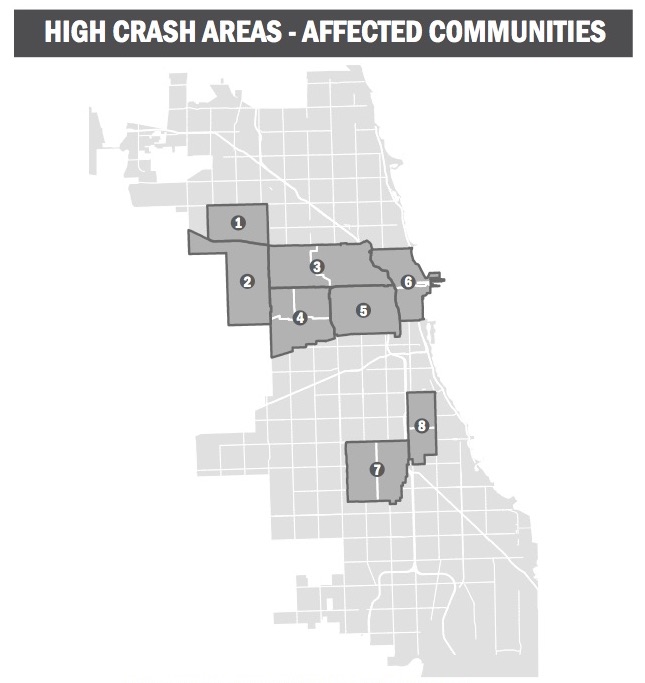

As part of the planning process the city used crash data to identify 43 High Crash Corridors and eight High Crash Areas. All of the High Crash Areas, save for downtown, are located on the south and west sides. (The plan attributes the high crate rate in the central business district to high population density and large amounts of vehicle and foot traffic.) The goal is to reduce the number of serious crashes in both the High Crash Corridors and High Crash Areas by 40 percent by 2020.

The plan out lines a number of strategies to reach these benchmarks by the three-year deadline. CDOT plans to improve 300 intersections across the city to improve pedestrian safety, using over $1 million in ward money earmarked by aldermen to fund the infrastructure, along with a variety of other funding sources, including arterial resurfacing projects, safe routes to high school projects, streets for cycling projects, and various capital projects. The department will also work with the CTA to upgrade safety and walking access to 25 el stations.

The document also calls for phasing in the installation of truck side guards, which help prevent pedestrians and bike riders from falling underneath the vehicles, and convex mirrors on city fleet vehicles and other commercial trucks. That’s especially welcome because half of the six 2016 Chicago bicycle fatalities involved right-turning flatbed truck drivers striking young adults on bikes, who were then crushed under the wheels. On June 28 Emanuel introduced the Large Vehicles Safety Equipment Ordinance, which will require city contractor vehicles to install the safety equipment starting July 2018. The city fleet will begin adding the gear as well. [Update: The ordinance passed in City Council on July 26.]

The lower-income areas most heavily impacted by traffic violence will be prioritized for safety outreach and education, beginning with a pilot program this summer in Austin, North Lawndale, and Garfield Park, funded by a $185,000 grant from the National Safety Council. The summer initiative focuses on working with local community groups and residents “to identify barriers to safe mobility and equitable solutions to improving traffic safety,” according to CDOT spokesman Mike Claffey. (A separate outreach process for the downtown High Crash Area is slated to begin in late summer or early fall.)

The phrase “equitable solutions” to reducing crashes means strategies that don’t involve racial profiling or unfairly targeting these African-American communities for a ticketing surge. The issue of “driving while black,” police unfairly stopping motorists of color, is well documented in Chicago – the ACLU reported that in 2013 nearly half of the drivers detained by Chicago police were black, even though African Americans make up only 32 percent of the city’s population.

In February the Chicago Tribune’s Mary Wisniewski reported on wild discrepancies between the number of biking tickets written in black communities and majority-white ones. Black bike advocates I interviewed said they believe zero-tolerance policing of cyclists in communities of color is used to justify stop-and-frisk searches. So it’s important that Chicago’s Vision Zero plans acknowledges the need for equitable enforcement, an issue that was previously raised by civil rights activists in Vision Zero cities like New York.

At the time of the Chicago plan’s release, police superintendant Eddie Johnson promised that his department’s strategies for reducing traffic violence as part of the initiative would be community-driven and fair. “Working with our partners in city agencies and with community residents, we will engage in appropriate enforcement efforts in the areas that have presented historical challenges with traffic related injuries and fatalities."

However, my writing partner Steven Vance has argued that the city of Chicago may have gone overboard in its efforts to avoid accusations of an unfair crackdown by minimizing references to traffic enforcement in the plan. “Goals are appropriate,” he tweeted on the day the document was released. But he added that “The role of police is downplayed. A lot.”

Vance noted that the plan states that it “does not use increased traffic citations as a measure for success.” He argued that increasing the number of citations for reckless driving would a way to change the city’s safety culture.” Vance added that you can count on one hand the number of times the word “enforcement” appears in the 88-page document.

When I raised the issue at last month’s Mayor’s Bicycle Advisory Council meeting, CDOT’s Vision Zero manager Rosanne Ferruggia argued that while ticketing isn’t being used as a metric for success, that doesn’t mean the police don’t have a key role to play. “We’re not saying that we’re not going to enforce traffic laws,” she said. “What we’re saying is that we’re not going to start ticketing people without talking to you first.”

Ferruggia underscored the importance of getting community input and buy-in before launching new traffic enforcement strategies. “We’re going to be going out and having conversations about what the priorities are, what’s fair, what’s just, and what do we need to be working on,” she said. “There are a lot of other priorities in these areas… So we want to make sure we’re coming in and listening to what is happening in the communities before we prescribe something that could have an adverse effect on the residents.”

CDOT Commissioner Rebekah Scheinfeld added that the plan’s focus is on “education and engagement,” including enforcement stings that involve officers warning motorists about dangerous behavior, such as not yielding to pedestrians in crosswalks, rather than ticketing them for it. Along with better street design, “that’s where we think we have the opportunity to really move the needle,” Scheinfeld said.

As the CDOT staff acknowledged, enforcement is definitely going to need to be a piece of the puzzle for reducing Chicago’s unacceptable traffic violence numbers, which disproportionately impact black communities. But there’s also the challenge of maintaining citizens’ rights to move freely through public space, regardless or where they live or what their skin color, especially in light of the CPD’s dismal record on civil rights. Achieving both of these goals is definitely going to be a balancing act.