Last Saturday work ceased at one of Logan Square’s newest construction sites for a high-end transit-oriented development. Representatives from the anti-displacement groups Somos Logan Square, the Autonomous Tenants Union, and Grassroots Illinois Action blocked access points to the site at 2501 West Armitage Avenue. (Disclosure: I am a member of GIA.)

At this location, a former vacant lot located a short walk from the O’Hare Branch’s Western station and an entrance to the Bloomingdale Trail, Spearhead Properties is building a 78-unit building with relatively few car parking spaces. Rents are expected to start at $1,300 for a studio. The activist were there to protest this project, as well as larger phenomenon of upscale TOD construction along the Blue Line corridor, especially in the First Ward, where alderman Joe Moreno has supported this type of housing. They say the TOD trend is accelerating the pace of poor and working-class people being displaced from the neighborhood.

Protesters picketed the site while chanting slogans like, “Hey Moreno! What will it be? Luxury or family?” and “¿Que queremos? ¡Viviendas económicas!” (“What do we want? Affordable housing!”). Others took more extreme measures. Two activists locked themselves to cement barrels in the front and back of a construction crane, while four more were locked down in front of one of the site entrances. The demonstration and blockade continued for about four hours, with no arrests made.

The current wave of upscale TODs on and near Milwaukee Avenue was spurred by a recently passed city ordinance which waives the usual off-streets parking requirements and allows additional density for projects near train stations. This transit-friendly, parking-lite housing makes it easy for tenants to live without owning a car. Groups like the Metropolitan Planning Council have also argued that building new market-rate housing in gentrifying neighborhoods takes pressure off the existing rental market and helps prevent tear-downs -- multi-unit buildings being replaced by luxury single-family homes.

However, the activists say the pricey new apartments are contributing to higher property values, property taxes, and rents in the area, which are forcing out many longtime residents, especially Latinos. In May DNAinfo reported that between 2000 and 2014, the number of Latino residents in Logan Square dropped by about 19,200, a 35.6 percent decrease.

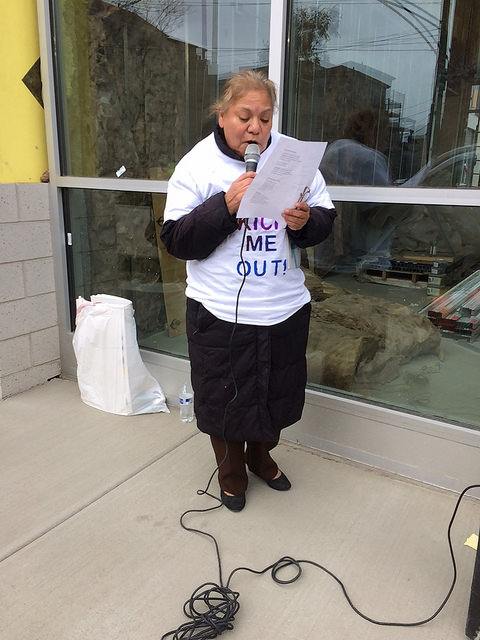

“We are tired of our community being taken from us,” said Alma Zamudio, a member of Somos Logan Square. “We have tried everything. We collected signatures against the Twin Towers [a controversial high-end TOD near the California Blue Line stop.] We have had people go to community meetings. [Moreno and the developers] aren’t willing to negotiate with us.” Zamudio said that blockading TOD construction sites is a way to draw attention to what they see as a displacement crisis in the midst of the Logan Square development boom.

The activists note that the real estate gold rush in Logan Square isn’t just making it harder for longtime residents to pay their property taxes or rents. It’s also leading to evictions as existing multi-unit buildings are sold and rehabbed to create fancier, more expensive apartments. In some cases, buildings with lower rents are being torn down and replaced by upscale housing.

In general, Logan Square TODs generally are replacing vacant lots or retail sites, rather than existing residential buildings. But in September the activists protested the planned eviction of tenants from a two-story, mixed-use structure at 2330 N. California that will be replaced by a 138-unit TOD tower.

Rosalinda Hernandez, who participated in Saturday’s protest, is a working-class resident who has experienced the eviction issue firsthand. Cleaning homes and doing other low-wage work for about 52 hours a week, Hernandez makes about $2,000 a month. In the summer of 2015, she found out the building where she was renting had been sold and she was given notice to vacate her apartment. After a prolonged fight to stay in her home, Hernandez was left homeless.

“I had to live out of my car for two weeks,” Hernandez said in Spanish at the demonstration. Her church eventually helped her raise funds for an apartment that rents for just over $800 a month but, since this represents 40 percent of her income, it’s still a struggle make ends meet.

Hernandez’s experience has inspired her to speak out in support of other tenants who are struggling as the area gets more expensive. “We need more affordable housing,” she said passionately. “We need public housing. We need tax relief for low-income homeowners. We especially need rent control and an end to luxury development with rents of $1,300 for a studio.”

Activists aren’t alone in being critical of the rising rents in Logan Square. Leading up to election, volunteers from Somos Logan Square and other groups went door to door in five of the First Ward’s 44 precincts, collecting enough signatures to get a non-binding referendum on affordable housing included on the ballot for the November 8 election in these precincts. The referendum asked, “Shall the First Ward require that at least half of newly constructed residential units cost no more than a third of an average Chicago tenant's income?” 77 percent of the voters in these five precincts, including the 16th precinct, where the Twin Towers are located, voted yes.

Unlike most Chicago aldermen, Moreno already requires developers to include to set aside ten percent of units for affordable housing, as defined by the city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance, before he will approve zoning changes, instead of letting them take the cheaper route of paying into the city’s affordable housing fund. As a result, the 2501 W. Armitage development will include seven affordable units, and the 2330 N. California tower, planned by Savoy Development, will feature 20 affordable apartments. (Savoy owner Enrico Plati declined to comment for this article; Spearhead Properties and Moreno’s office did not respond to interview requests.)

However, as the ballot referendum indicates, thousands of Logan residents feel that ten percent is insufficient. Morover, the activists have questioned the city’s definition of affordable housing. According to the ARO, affordable units “must be affordable to households earning up to 60 percent of Average Median Income [for the Chicago region].” That translates to about $46,000 for a family of four, which Zamudio says is out of reach for the average Latino family in the Logan Square area. Somos and other groups are calling for the set-aside units to be made affordable for the average rental household income in the Chicago region, which is $35,422 according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Sabrina Morey, 39, who grew up in Logan Square, hopes the campaign for lower rents will be successful so that she’ll be able to move back to her childhood neighborhood. At the protest she fondly remembered living near Fullerton and Drake, but also recalled the first time she realized the area was no longer affordable for lower-income people. “One morning I woke up and my community was taken from me,” she said. “A person like me can’t get an apartment in a neighborhood like this.”

After being forced out of her Logan Square apartment due to a rent hike, Morey, like Hernandez, experienced homelessness before eventually settling farther northwest in Belmont Cragin, where the cost of living was lower. While she would like to return to Logan Square, if the trend towards higher rents continues, she’s not even sure she’ll be able to remain in the city. “If things keep going the way they are, we are all going to be pushed out of Chicago,” she said.

Did you appreciate this post? Consider making a donation through our PublicGood site.