A new study concludes that most U.S. bike-share cities, including Chicago, have provided much better access to stations for whites than African Americans. The report is based on fall 2014 Divvy station location data, but the coverage area has greatly expanded since then to include many more communities of color, so it's likely that geographic access has significantly improved. However, it's clear that more work needs to be done in Chicago before the system can be considered truly accessible to African-American and Latino residents.

Julia Ursaki and Lisa Aultman-Hall from the University of Vermont's Transportation Research Center conducted the study and presented it in January at the Transportation Research Board's annual meeting. Ursaki and Aultman-Hall compared bike-share access to population demographics in Chicago, Seattle, Boston, New York City Washington, D.C., and Arlington, VA.

Aultman-Hall told me via email that, for the purposes of this study, the terms "equity" and "equality" had the same meaning. "'Equity' is a bike share station in all neighborhoods, in the context of this paper," she said. "That is also 'equal.' We had no measure of need, alternatives or destinations. In a more complex [study], one would also have to consider if the activities or destinations needed were accessible by bicycle from the neighborhood."

Ursaki and Aultman-Hall also reviewed previous bike-share studies and noted there are at least three main factors cities have taken into consideration when designing bike-share systems: market viability, health indicators, and economics. One such study found that the "primary market" for Philadelphia's Indego bike-share system existed chiefly in the central business district.

However, a second study found that if the Indego operators were interested in improving public health, they should install bike-share stations in mostly African-American West Philly. A third study asked various bike-share operators how they were trying to address equity. The operators responded that, among other initiatives, they were installing stations and other bike infrastructure in low-income areas.

CDOT spokesperson Mike Claffey told me the department looks at "a variety of equity-related criteria" when choosing station locations, including "median household income, non-white population levels, and educational attainment," but they don't consider health indicators such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease rates.

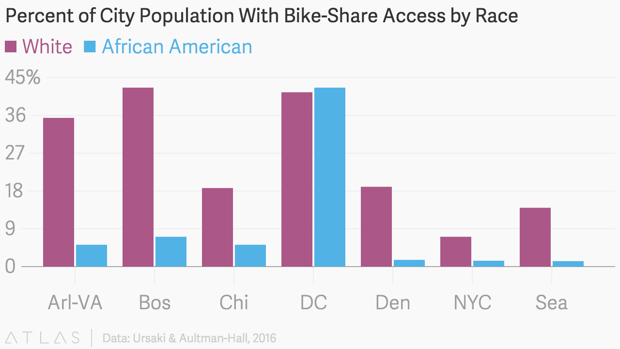

Ursaki and Aultman-Hall found that, in terms of several socioeconomic factors, Washington, D.C.'s Capital Bikeshare stations have the most equitable distribution of the seven cities they studied. That system, which debuted in 2010, is also the oldest. Neighboring Arlington is part of the same system, but its station distribution was reviewed separately.

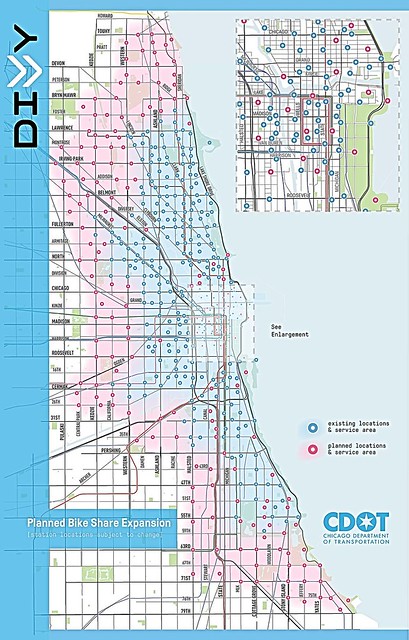

Divvy launched in summer 2013 with 300 stations. While the initial service area extended about the same distance north and south of the Loop, areas with a higher density of people and destinations received a higher density of stations. Stations were generally placed every quarter mile in these areas, versus every half mile in other areas.

At the time, CDOT said this strategy was necessary to ensure that the system would be economically sustainable. However, this meant that stations tended to be concentrated in relatively affluent, largely white neighborhoods.

Using fall 2014 station location data, which only included the first 300 stations, Ursaki and Aultman-Hall found that a mere 5.2 percent of African Americans in Chicago lived within 500 meters (0.31 miles) of a station.

Using the same station location data, a Chicago Tribune analysis found that while only 15.7 percent of the city's African American residents lived within 0.25 miles (402 meters) of a station, and only 18.8 percent of Latino Chicagoans did, a full 47.9 percent of the city's white residents had quarter-mile access .

However, in summer 2015 CDOT added 176 stations, with many of them going to African-American and Latino communities. Claffey said that CDOT has done its own analysis of demographics in the current Divvy service area. He said they found that, of residents who now live within 0.5 miles (805 meters) of a station, 46 percent are "non-white."

Last January, CDOT announced that Divvy will be adding 96 new stations this year, mostly in African-American neighborhoods within the city. Claffey said they haven't yet analyzed what the demographics of the Divvy service area will be after the expansion. But it's obvious that the 2016 expansion will increase the percentage of Chicago African Americans who live near a station.

However, even though the 2015 expansion improved geographic access for people of color, more needs to be done to remove other barriers to using the system. A 2015 CDOT survey of hundreds of bike-share members found that 79 percent of respondents were non-Hispanic whites – a group that makes up only about 32 percent of the city’s population. In addition, the majority of those who filled out the survey had middle-to-upper incomes, and 93 percent had a college degree or more.

In July 2015, the city took a positive step to address Divvy's economic divide by launching the Divvy for Everyone program. This initiative offers one-time $5 memberships to low-income residents, waives the usual credit card requirement, and allows people to sign up in person instead of requiring internet access. Nearly 1,100 people have signed up for the discounted memberships as of last month.

I asked Aultman-Hall if she and Ursaki might update the study using current Chicago station location data. "At this time we do not have funding for further study but we are encouraged by how many organizations are doing similar work," she said, adding that a researcher at University of California, Davis is conducting a similar study. "[Our] analysis is far from perfect. It is limited by data. We were just happy to be able to put some numbers to a problem planners were aware of but had not quantified."