The Chicago Tribune’s David Kidwell and his colleagues have written extensively about the city’s red light camera program. Some of that reporting has been constructive, including revelations about the red light cam bribery scandal, unexplained spikes in ticketing, and cameras that were installed in low-crash locations during the Richard M. Daley administration.

Other aspects of the Tribune’s red light coverage have been problematic. For example, the paper emphasized that the cams have led to an increase in rear-end crashes with injuries, while downplaying the fact that they have decreased the number of right-angle injury crashes, which are much more likely to cause serious injuries and deaths.

Throughout it all, Kidwell has shown a strong bias against automated enforcement in general. He has largely ignored studies from cities around the country and the world that show red light and speed cams are effective in preventing serious injuries and fatalities.

Yesterday morning, Kidwell and fellow reporter Abraham Epton unleashed a new assault on the city’s speed camera program, the product of a six-month investigation. In three long articles, they claim that the city has issued $2.4 million in unfair speed camera tickets, and argue that many of the cams on busy main streets are justified by small or little-used parks.

If there really is a significant problem with speed cams writing tickets when warning signs are missing or obscured, or after parks are closed, or in school zones when children are not present, contrary to state law, it’s a good thing that the Tribune is drawing attention to this phenomenon. If so, the city should take steps to address the problem, as they did in the wake of Kidwell's red light cam series.

Most of these issues can be traced to the city of Chicago’s questionable decision to propose state legislation that only allows the cameras to be installed within the eighth-mile “Child Safety Zones” around schools and parks. Instead, the city should be allowed to put cams anywhere there's a speeding and crash problem.

However, it appears this new series is written from Kidwell’s usual perspective that it’s unfair to force motorists to pay more attention to driving safely. For instance, the coverage discusses how Tim Moyer was ticketed on five different occasions for speeding past a Northwest Side playground that was closed for construction -- speed cams in park zones are only supposed to be turned on when the park is open. After the Tribune contacted the city about these tickets, they were thrown out.

The Trib uses this as an example of how the speed cam program is dysfunctional. However, the cams only issue tickets to drivers who are going 10 mph or more over the speed limit. The fact remains that Moyer was caught speeding heavily on five different occasions at the same location. Even if the cam couldn't legally issue him tickets, he deserved them.

The Tribune's new anti-speed cam series seems to be largely about helping drivers like Moyer who speed by 10 mph or more get off on technicalities. But the city’s default speed limit is set at 30 mph for a good reason – studies show that pedestrians struck at this speed usually survive. Why is the Tribune putting so much effort into defending the right of drivers to go at or above 40 mph, a speed at which pedestrians crashes are almost always fatal?

I haven’t fully digested all three of the articles yet, but I plan to publish a more thorough analysis in the near future. In the meantime, let’s talk about something that Kidwell and Epton largely ignored: the positive effect the speed cams are having on safety.

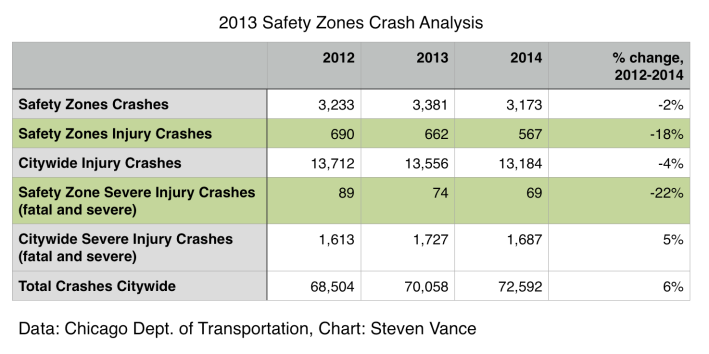

On Tuesday evening, in a preemptive strike against the Tribune coverage, the Chicago Department of Transportation released a preliminary analysis of Illinois Department of Transportation crash data, which suggests the city’s speed camera program is working. CDOT found that the number of crashes with injuries dropped by four percent citywide between 2012 (the year before the first speed cams were installed) and 2014.

However, the department found that injury crashes dropped 18 percent within the 21 safety zones where speed cams were installed in 2013 – a major improvement. Fatal and severe crashes within the safety zones went down a full 22 percent.

Moreover, while CDOT found the total number of crashes, including those with no injuries, went up by six percent citywide during this period, the total crash number within safety zones dropped by two percent. “This is just one year’s worth of data,” CDOT Commissioner Rebekah Scheinfeld acknowledged in a statement. “But we are already seeing a positive, downward trend in the number of crashes causing injuries in Child Safety Zones.”

It’s important to keep in mind that these numbers don’t take into account possible changes in the number of people driving, walking, and biking within the safety zones during 2012-14 analysis period. For example, if many drivers are avoiding these areas due to the presence of cams, the drop in crashes is somewhat less meaningful. On the other hand, if that means there are fewer cars passing through safety zones, that’s a good thing for school students, park users, and everyone else who lives or travels in these areas.

The CDOT press release also mentions they’ve found that, on average, speeding violations drop by 53 percent within 90 days after speed cams are activated. In addition, 67 percent of drivers who were ticketed in park zones didn’t rack up a second violation, and 81 percent of those who were ticketed in school zones avoided a second violation.

In short, the CDOT analysis seems to show that the speed cams are having a very positive effect on safety, not just for kids, but for everyone. That’s something you won’t read about in Kidwell and Epton’s latest crusade against automated enforcement.

![]()

Did you appreciate this post? Streetsblog Chicago is currently funded until April 2016. Consider making a donation through our PublicGood site to help ensure we can continue to publish next year.