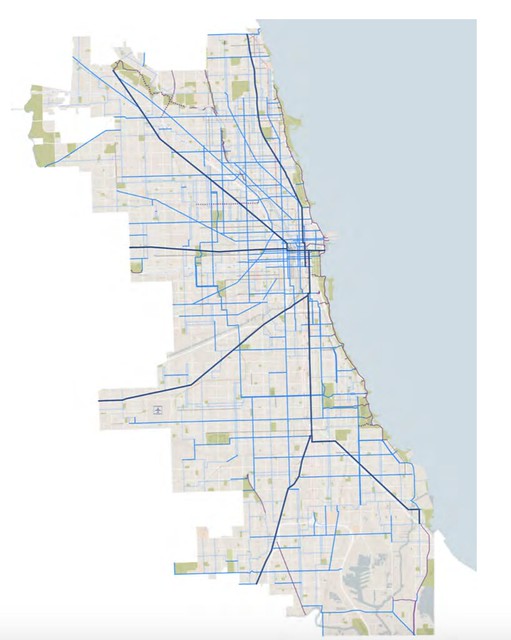

In the past, residents and aldermen in wealthier wards have been more vocal about pushing for bike infrastructure than their South and West Side counterparts. That’s one reason why there's currently a higher density of bike lanes downtown and on the North and Northwest Sides. However, the Chicago Department of Transportation says they want to help level the playing field with a new bike lane planning process that focuses on underserved neighborhoods on the South and West Sides, with an emphasis on in-depth public input.

Mike Amsden, CDOT’s assistant director of transportation planning, outlined the plan at lat week’s Mayor’s Bicycle Advisory Council meeting. Amsden said the department has already tried to install bike lanes in a more equitable way as part of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s goal of building 100 miles of buffered and protected bike lanes in his first term. He noted that 60 percent of the lane mileage installed since Emanuel took office in 2011 has gone to South and West Side communities.

“We really wanted to start to build a backbone of a network in areas of the city where historically we didn’t have a lot of bike infrastructure,” Amsden said. “By no means are we there yet, but I think we’ve made a lot of progress. We’ve gotten to the point where the 100-mile goal is met, so now we need to figure out where do we go now.”

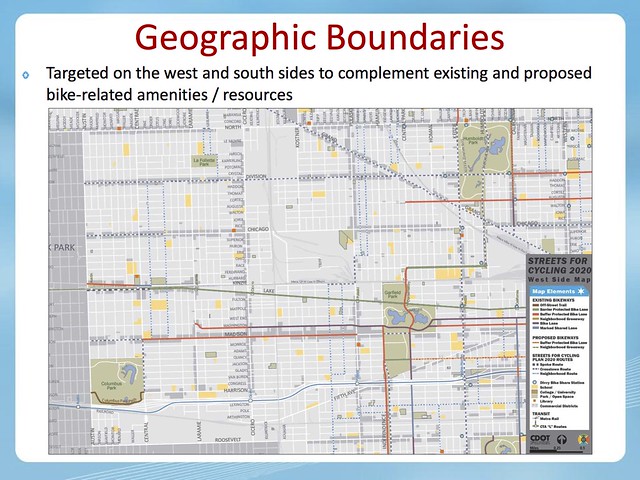

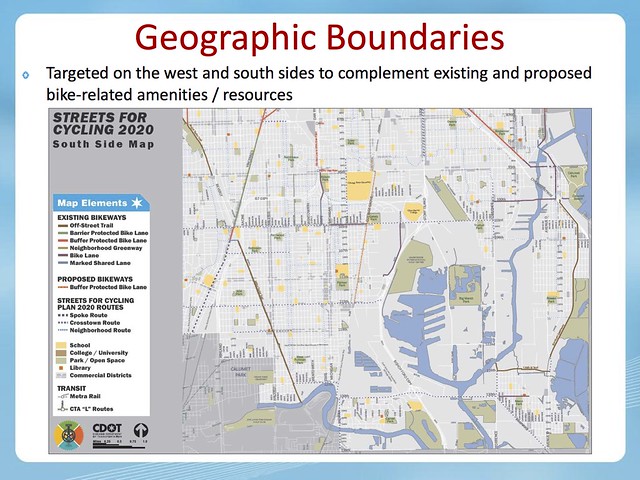

In 2012, after an extensive community input process, CDOT published the Streets for Cycling Plan 2020, which outlines a 645-mile network of proposed lanes, paths, and neighborhood greenways. When deciding on which of these routes to build first, CDOT doesn’t just want to concentrate on the parts of the city where cyclists and aldermen are already requesting more infrastructure, Amsden said. That’s why the department is piloting an approach that involves proactively asking South and West Side leaders and residents where they believe bike lanes are needed sooner than later.

“We may look at a map and think a connection to a major park is the most important thing, but we don’t live in these communities,” Amsden said. “We need to talk to people in the neighborhoods to really understand what is most important,” he said. This includes residents who don’t currently ride bikes.

By consulting with average residents, not just cycling advocates, the department can help build support for new infrastructure, Amsden said. “People are starting to realize the benefits of bicycling for health, accessing jobs, and saving money,” Amsden said. “We want people to know why bicycling is important so that, even if they don’t ride, they understand why someone might want to ride a bike in their community.”

The West Side pilot will cover the area roughly bounded by North Avenue, Roosevelt Road, the western city limits, and Humboldt and Garfield parks, including the Austin, Garfield Park, and Humboldt Park communities. “We’ve done a lot of east-west connections there, but we’re really lacking in north-south connections,” Amsden said. Better bikeways in the area will compliment the expansion of Divvy bike-share into these neighborhoods and Oak Park, slated for next year.

The South Side project will include the area roughly bounded 87th Street, the southern city limits, the Major Taylor Trail, Lake Michigan, and the Indiana state line. Amsden noted that this district has many existing or planned bike amenities, including the Major Taylor Trail, the Burnham Greenway, the South Chicago Velodrome, and Big Marsh bike park, and the nearby city of Hammond, Indiana, has been doing “a lot of really cool work with trails.” However, the area lacks good bike connections between these facilities.

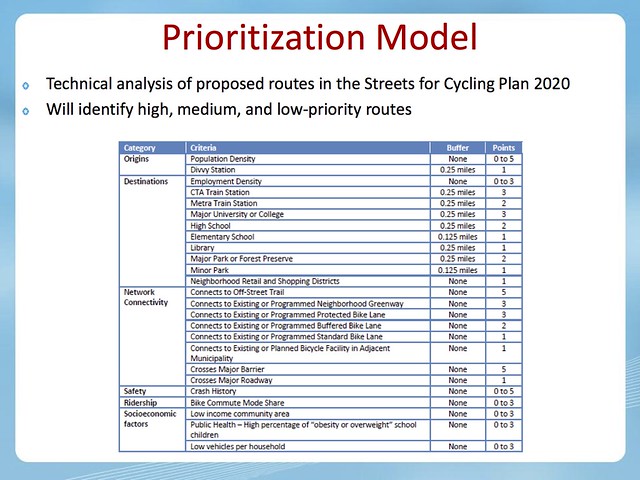

The pilot, which will hopefully develop into a model that can be used citywide, involves a two-prong strategy. First, CDOT will do a technical analysis of bike routes in the 2020 Plan, looking at destinations, crash history, and socioeconomic indicators such as income, childhood obesity, and car ownership, which suggest the areas that could benefit the most from better bike access. After crunching the numbers, they’ll identify possible priority routes. Amsden said the department should complete this process this fall and provide an update at the December MBAC meeting.

The second prong is a full community input process. CDOT has already been in talks with three aldermen in each of the two pilot areas, as well as the Active Transportation Alliance, and local advocates. With help from the ward offices, the department is currently putting together community advisory groups, including economic development organizations, chambers of commerce, health centers, and block clubs. “We want people who really know what’s happening in these parts of the city,” Amsden said.

Once CDOT has first drafts of the priority routes list, they’ll run them by the advisory groups later this year or early next year, so that the networks can be tweaked as necessary. In the late winter or early spring, the department will hold public hearings where citizens can provide further input on the routes. The advisory groups will help spread the word about the meetings.

Once the plans are finalized, CDOT can identify bike lanes to build in the near future. “One benefit of this process is, if we do a project in 2016 and it looks like it’s on an island, people will understand why the project is happening, and what’s coming next,” Amsden said.