Last week, the Metropolitan Planning Council launched the “Grow Chicago” campaign to promoted transit-oriented development. The city’s current TOD ordinance, passed in 2013, reduces the minimum parking requirement and allows additional density for new and renovated buildings located within 600 feet of a rapid transit stop, 1,200 on a designated Pedestrian Street. Among other recommendations, the Grow Chicago report calls for revising the ordinance to include all buildings within 1,200 feet of a station, dropping the parking minimums altogether within these zones, and streamlining the approval process for TOD projects.

Today, Mayor Rahm Emanuel proposed a new TOD reform ordinance that would essentially grant all of these wishes by expanding the TOD zones and abolishing the parking minimums. The new law would also create new incentives for including on-site affordable housing in TOD projects. The ordinance will be introduced at Wednesday’s City Council meeting, and the council will likely vote on the legislation in September, the two-year anniversary of the original law.

“From day one of my Administration, we have invested in our public transportation system to create jobs and revitalize commercial corridors across Chicago,” said Emanuel in a statement. “This ordinance will build on those investments, spurring economic development in our neighborhoods, which will benefit residents and small business owners alike.”

Although the new ordinance is closely aligned with MPC’s goals, and the nonprofit was given a sneak peek at the bill in order to provide an initial analysis of the new law, the group wasn’t directly involved in drafting the legislation, according to MPC spokeswoman Mandy Burrell Booth. “We’ve been having conversations with the city over the past several months, and this came out of those talks,” she said.

The 2013 ordinance has facilitated eight projects worth more than $132 million, creating almost 1,000 construction jobs and 100 permanent jobs, according to the mayor’s office. “Groups like MPC and developers have seen how successful the 2013 ordinance has been in spurring development near transit, so this was a natural next step to capitalize on that success,” Burrell Booth said.

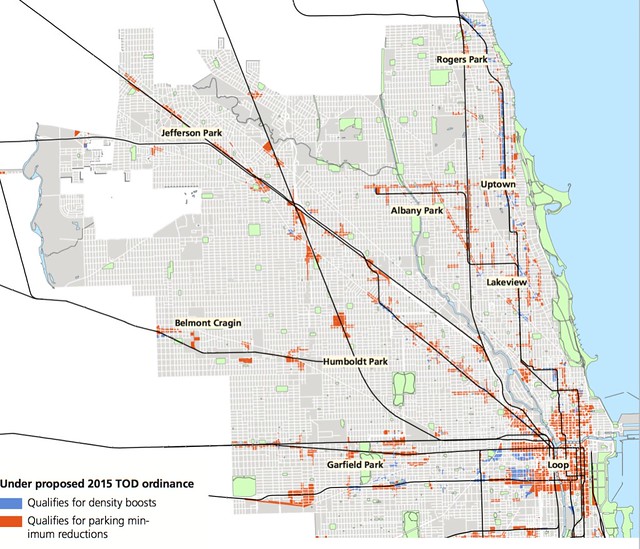

The new law would more than double the reach of the 2013 ordinance. Currently, new residential buildings within 600 feet of a Metra or ‘L’ stop (1,200 feet on designated Pedestrian Streets) are required to provide at least a 1:2 ratio of parking spots to units, instead of the usual 1:1 ratio. The parking requirement for commercial uses, or the commercial portion of a mixed-use development, is waived.

Under the reform ordinance, land zoned for business (B), commercial (C), downtown (D) or industrial (M) uses within 1,320 feet of a station would be freed from the minimum parking requirements altogether, including for residential uses. On Pedestrian Streets, the zone would be expanded to 2,640 feet.

Note that the elimination of parking minimums does not mean that all TOD developments would have zero parking spaces. Rather, it leaves the decision about how many spots should be provided up to the developer and the community, instead of having the zoning ordinance dictate that number. Since off-street parking spots cost at least $20,000 each, dropping the requirement for unneeded spaces will help reduce housing costs.

The legislation would also increase the density allowance for parcels within these new TOD districts that are zoned B, C, or D, with a floor area ratio of 3 (roughly equivalent to three stories), if the developer provides on-site affordable housing. Buildings in which 2.5 percent of the housing units are affordable would receive an upzone to a FAR of 3.5. Those with five percent affordable units would qualify for a FAR of 3.75, and those with 10 percent affordable units would be eligible for a FAR of 4. This would help make it easier for working people to access jobs via transit.

To facilitate the approval process for TOD projects, the reform ordinance would allow the elimination of parking requirements and approval of increased density to take place on an “as of right” basis, through the Administrative Adjustment process. Currently, a zoning map amendment is generally required for these changes, which is a slower, more expensive, and riskier process.

MPC’s initial analysis found that the policy change would more than double the area of land parcels eligible for the density bonus, compared to the 2013 ordinance, from 13 million square feet to 31 million. Meanwhile, it would increase the amount of land benefitting from the parking minimum elimination from 86 million square feet to 957 million.

The nonprofit projects that, over the next 20 years, the reform would result in a total of 60,000 to 70,000 units located within a half mile of transit, about a 50-percent increase in the number that would be build if the 2013 ordinance went unchanged. If the ordinance passes, the number of units would include about 1,300 on-site affordable units, and developers would also pay an estimated $150 million towards the city’s affordable housing fund.

Financial benefits of the new ordinance would also include roughly $450 million in additional annual sales at businesses around the, according to MPC. The city of Chicago and sister agencies would receive additional annual tax revenues of almost $200 million.

Arguably, a fly in the ointment of the new law is that, since the density bonus only applies to parcels with floor area ratios of 3, aka “-3 zoning,” plenty of land near transit won’t be eligible for this bonus. For example, while the Near West Side has plenty of -3 zoning near transit, Albany Park, which has two Brown Line stations, has very little of this kind of zoning. City Notes blogger Daniel Hertz tweeted his displeasure at this oversight:

@shylobisnett Still annoyed that it only applies to -3 zoning. It's nuts that every major street near an L station doesn't have that. — Daniel Kay Hertz (@DanielKayHertz) July 27, 2015

I asked Peter Strazzabosco, deputy commissioner of the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, why the city chose to only include -3 parcels for the density bonus. "In a nutshell, the [Minimum Lot Area], FAR and height provisions in the proposed ordinance would provide for new projects that are compatible with the medium- to high-density character of existing -3 areas, versus other business and commercial locations that could be considered as having low-density zoning," he said.

It’s likely that the TOD reform ordinance will pass City Council, but there’s a strong possibility that it will get watered down somewhat. For example, council members will likely ask that the requirement of an alderman-approved zoning map adjustment for the density bonus stay in place -- they made a similar move back in 2013. They’ll probably argue that this is to make sure they stay in the loop about new developments, but the desire to keep campaign contributions from developers flowing may be another reason to resist this change.

Overall, however, the reform ordinance promises to be a big win for Chicago. Encouraging development near transit, providing more affordable housing, making it easier for people to access jobs, increasing retail sales and tax revenue – these things are exactly what the city needs right now.

On a humorous note, the Chicago Tribune, which was given the scoop on the story by the mayor’s office, managed to spin this big news about housing and transit into a bikes-versus-cars narrative. Reporter Alexia Elejalde-Ruiz focused on the fact that developers would have to provide one bike parking spot per housing unit, plus a car-sharing spot or a Divvy station on-site, in order to qualify for the elimination of the car parking requirement. “Cars Make Way for Bikes in Transit-Oriented Housing Proposal” trumpeted the headline, illustrated by a photo of a hipster on a fixie in Wicker Park.