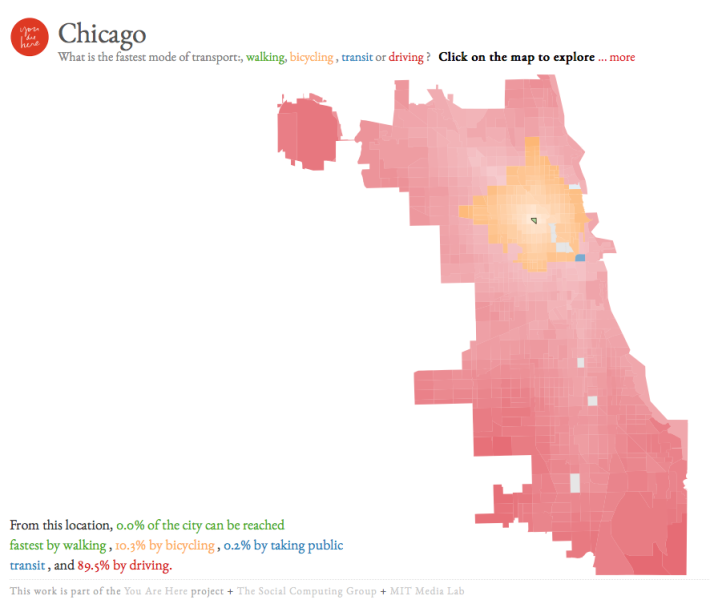

Researchers at the MIT Media Lab published an interactive map this week that shows a new way to measure access across Chicago via different transportation modes. Instead of assessing how far one can travel by a certain mode, like a previous online map has shown, or showing the cost of travel, this map looks solely at relative travel time across four modes.

Click on any census block group within city limits, and the map will show you what mode would be the fastest way to every other part of the city, and uses shading to show how long that mode will take. The map uses data from Google Maps's Directions service.

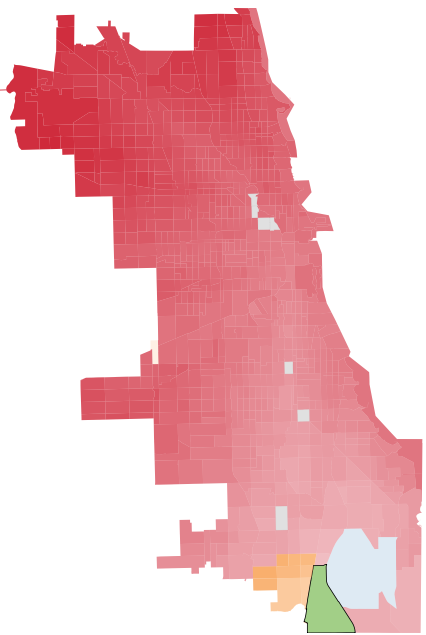

Walking is only the fastest way to get anywhere within the block group you choose, while bicycling is the fastest transportation mode to any place up to two miles away. Most places in Chicago are reached quickest by driving: In a 227-square-mile city like Chicago, most of the city's area is going to be more than two miles away. Also, dozens of square miles of the city are not particularly useful or easy to reach, like Wolf Lake or the runways at O'Hare airport.

But in many relatively central neighborhoods, bicycling can be the quickest way to access a good chunk of the city.

Start in Wicker Park, and you'll find that bicycling is the fastest way to reach 10.1 percent of Chicago, an area spanning from the Gold Coast to Ravenswood to the edge of Austin. Start in Lakeview, and that drops down to 5.9 percent, in part because Lake Michigan means that half of the bikeable area is underwater.

It appears, though, that the corner of Chicago which wins the prize for having the most bike-accessible area is tucked away on the southwest side. Two different areas -- an industrial part of Bridgeport, and the area around Marie Curie high school -- can reach 11.3 percent of the city fastest by bicycle. This is perhaps because, from those points, public transit is the fastest option to nowhere.

Chicago's breadth relative to other cities becomes very apparent when comparing these bikesheds. For one patch of the Capitol Hill neighborhood in Washington, D.C., bicycling is the fastest way to reach 62.7 percent of the city. D.C.'s much smaller size (63 square miles) and square shape puts much more of the city within that two-mile radius.

Surprisingly, even from the core of downtown near Willis Tower, driving is the fastest way to reach 95.1 percent of the city, while transit wins for only 1.3 percent of the city, walking for 0.2 percent, and bicycling for 3.4 percent. This might be because it's surrounded by so many high-speed streets and highways that driving, especially without considering traffic, appears to be fast.

How far can you go by transit from Willis Tower and still get there faster than if you drove? Within the city, one spot shows up at 95th Street in Beverly, where Metra's Rock Island District route is the quickest way downtown. Even though Beverly's also adjacent to interstate I-57, the train still gets you there faster.

Move out to the edges of the city, and driving becomes the default fastest mode of travel. From Altgeld Gardens, the city's furthest south neighborhood, large parts of the city are deep red, indicating that even with a car it would take well more than half an hour to travel there, and sometimes an entire hour. The secluded neighborhood entirely lacks other transportation options: Its 3,000 residents use a packed bus route, and don't even have sidewalks or bike lanes to get to bus stops along high-speed 130th Street -- much less to reach even adjacent neighborhoods. A forthcoming extension of the Red Line would significantly reduce transit travel times from Altgeld.

When the map calculates driving times, it adds a buffer for parking and walking time, but not for traffic congestion. In a future version, researchers will add more factors that contribute to the total cost of a trip, including pollution, fuel, and vehicle costs.